Behold man: so poor at seeing what’s right in front of him, so blind at times to the obvious. “People pay a lot of money to go on whale-watching tours, but the largest land dwellers are trees, and they remain unknown to us.”

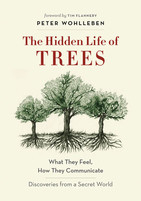

So says Peter Wohlleben, a towering German in his early fifties. Short gray hair, neatly dressed, eyes twinkling behind his spectacles. In his workaday life Wohlleben is a forester; he spends his spare time writing books. One of his books, The Hidden Life of Trees, is meant to end humanity’s ignorance of these denizens of the forest. In it, Wohlleben initiates us into a world where trees have deep social bonds, communicate with one another, and come to the aid of ailing members of their species.

The once-entrenched hierarchy and dividing lines between people, animals, plants, and things are being called into question

Behold man: something about him is changing. Or at least the way he sees himself is. Roughly since the Renaissance, Western man has considered himself the measure of all things, a free and autonomous subject in a world of objects. But over the last two decades that anthropocentric worldview has begun to fray. Philosophers of technology now argue that objects have morals too, and that man is not as free and autonomous as he long thought himself to be. Primatologists continue to make discoveries that show the differences between humans and other primates to be less clear-cut than previously believed. Lawyers argue that nature, too, ought to have certain basic rights. Posthumanists say the humanist view of man is obsolete. From all sides, the once-entrenched hierarchy and dividing lines between people, animals, plants, and things are being called into question.

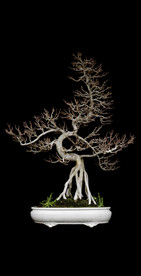

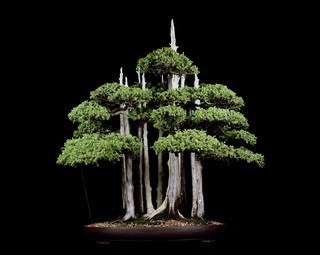

Untitled #2, The Bonsai Project: Typology. © Sjoerd Knibbeler and Rob Wetzer

Call it the emancipation of the non-human. Or a sign of the continued expansion of our “circle of empathy.” You could also call it the beginning of the end of man as the measure of all things. But is that really what’s going on? And if so, how will it affect the way we engage with plants, animals, things, and one another?

To answer those questions, in the coming months Anoek Nuyens and I will be speaking with a number of thinkers, scientists, and activists about this changing view of humanity, and reporting on our findings. That’s why I’m sitting here today with Peter Wohlleben: the book-writing forester is briefly in the Netherlands for the release of Hidden Life’s Dutch translation. For Wohlleben, fostering an understanding of “how wonderful trees are” is an important step toward a future he believes is ultimately inevitable. “I am convinced,” he says, “that we will come to talk about trees the same way we now talk about animals and animal welfare.”

Wohlleben’s new forest

The conviction that you can’t harm trees without a legitimate reason, can’t use them as a means to your own ends, that you must treat them in ways that suit their nature, that they even have legal rights – in the future envisioned by Wohlleben, all this goes without saying, and modern forestry will seem as much of an atrocity to us as the excesses of factory farming do now.

Wohlleben studied forestry and began his career in the 1980s with the German national forest administration. Later, the young forester was charged with the care of a forest near Cologne. There he applied what he had been taught at university: he exterminated insects and felled trees when they grew too close together.

In the wild, trees cooperate and support each other

But the more he delved into the science of trees, the more he became convinced that this course of action was at odds with the natural order: in the wild, trees cooperate and support each other – for example, by sharing water and nutrients through their roots so that every tree gets exactly what it needs. There’s no reason at all to cut down trees so that the remaining ones get more light, as is customary in Western forests.

Untitled #11, The Bonsai Project: Typology. © Sjoerd Knibbeler and Rob Wetzer

He visited communities that approach forestry the way organic farms approach food production. In these Plenterwald forests, trees of all ages and sizes grow side by side, trees are harvested only rarely and carefully, and part of the forest is protected so that old trees can continue to live.

“These forests produce more wood, the wood is of better quality, and the forest is more stable against storms or insect attacks,” Wohlleben says.

Ten years ago, the municipality that owned the forest Wohlleben had been managing for fifteen years decided to let him apply his newly acquired knowledge. He began using horses instead of heavy machinery to fell trees, eliminated insecticides, and let the forest grow wild and full.

The surprising parallels between trees and animals

Wohlleben began writing nearly ten years ago. After completing one of his tours through the forest, people often asked him where they could read more. Because the answer was “nowhere,” he decided to write a book himself.

Untitled #1, The Bonsai Project: Typology. © Sjoerd Knibbeler and Rob Wetzer

In The Hidden Life of Trees, Wohlleben focuses primarily on the often surprising parallels between trees and animals, and thus between trees and people. He couches scientific insights into the way trees communicate, reproduce, and collaborate in anthropomorphic terms. In short chapters with titles such as “Friendships,” “Social Security,” “Love,” “United We Stand,” “Burnout,” and “Street Kids,” he explains that trees form social networks, exchange information through a “Wood Wide Web” of roots and fungi, care for weaker or younger members of their species, and feel pain when their branches get broken off or their bark damaged.

“The aim of my first books”– Wohlleben has written sixteen to date – “was to make people recognize how roughly modern forestry treats our forests.” Whether the cause is profit-chasing and short-term thinking or a lack of knowledge, foresters routinely make faulty choices that weaken forests rather than improve their resilience.

“But that’s really sad to hear about,” Wohlleben says. “The books I wrote before are in a minor key. I tried to write this one in a major key, so that people first see how wonderful trees are. And that works better.”

The anthropomorphic phrasing – Wohlleben describes trees that “nurse” their young and forests that are “happy”; he compares pruning to a “massacre” – is a deliberate choice. “We have a lot of scientific research from the past 40 years” – such as the discovery that beeches share water and nutrients with each other – “but no one reads it, because scientists use bare-bones language devoid of emotion. Yet human life is perhaps 90% emotion.”

Untitled #4, The Bonsai Project: Typology. © Sjoerd Knibbeler and Rob Wetzer

The end of man as the measure of all things

“We have divided beings into animals and plants,” Wohlleben says, “but this division makes no sense. It’s just how they get their food. Even the way trees communicate” – through odors, electrical signals, and sounds – “is not so different from animals.” Young corn plants click their roots, for example, and other seedlings “hear” the sound and respond to it, by bending their root tips toward the source. “So the boundaries between plants and animals are dissolving.”

Wohlleben’s optimism about the coming change in humanity’s relationship with trees is not unfounded. More than 40 years ago, American law professor Christopher D. Stone wrote an essay titled “Should Trees Have Standing?” in which he argued that natural objects like trees, rivers, and oceans should also have legal rights.

If companies, municipalities, and countries can be granted personhood, why not trees and forests?

Just as the law once failed to recognize black people, children, or women as full-fledged persons and now does, argued Stone, so too will we soon admit our natural environment to the domain of legal representation. After all, if companies, municipalities, and countries can be granted personhood, why not trees and forests? A legal guardian could then represent their interests in the courtroom.

Here and there, Stone’s ideas are being put into practice. A river in New Zealand was recently granted the status of a legal entity, and in Ecuador that right belongs to all of nature. Advocates and activists such as Polly Higgins are working to pass a global law against “ecocide” – the destruction of nature. A few years ago, the Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature drafted a “Universal Declaration of the Rights of Mother Earth.” And in Switzerland, Wohlleben relates, “not just animals but also plants are protected by the constitution.” There, he says, it is illegal to cut roadside flowers without a very good reason.

The tree as a mirror for humanity

Any discussion of the rights and interests of non-humans inevitably involves a discussion about humanity. About what makes humans human, and what distinguishes us from other beings and objects. The Hidden Life of Trees likewise enables readers to reflect on the human world – if only through the parallels that Wohlleben draws between arborous societies and human ones.

The forest reminds us what a society can look like

“Modern scientists no longer look upon evolution as they did before, that is, as a struggle that pits each being against the rest. We’re living in a time when individualism is highly valued. But when we look at trees, they don’t act this way.” Trees support weaker ones because the forest as a whole functions better when everyone takes part. The forest, understood like this, serves as a reminder of what a society can look like.

Untitled #3, The Bonsai Project: Typology. © Sjoerd Knibbeler and Rob Wetzer

Perhaps that last point explains the book’s success. Or perhaps Wohlleben’s readers are so enthusiastic about trees – and about nature in general – because we are on the brink of losing them.

Climate change, dwindling resources, the realization that man’s influence on the Earth is so great that we can rightly speak of a new geological era, the Anthropocene; the consequences of our actions, it is becoming clear, are far-reaching and often irreversible. “We are losing more and more nature, and the nature we still have around is often shaped by human hands. The landscape has lost its soul. People are recognizing this, and they’re searching for a spot that feels good. But those spots are melting like snow in the sun.”

Maybe in the future we’ll only find those spots in Plenterwald forests like Wohlleben’s, or in the pages of books about trees. Or maybe that view of man as the unquestioned peak of the food chain and master over the Earth, as a uniquely autonomous and intelligent being with the attendant special rights and privileges, really will crumble in the coming years, under the influence of scientific, intellectual, and geological movements. And maybe our actions will drastically change as a result.

In the meantime, Wohlleben will continue to write. Not because it’s his passion or his profession – he just sort of fell into it, after all. But because writing, for him, “is just another way for me to guide people through the forest.”

— English translation by Grayson Morris

Untitled #8, The Bonsai Project: Typology. © Sjoerd Knibbeler and Rob Wetzer

More from De Correspondent:

How pictures of bonsai trees incensed our readers

Words generally come first in journalism, images are secondary. Usually. And that’s not entirely fair. A good Image Director will bypass the cliché and opt for the unexpected, to enrich stories in new ways. But when I chose bonsai photos for a story on the hidden life of trees, this approach led to unexpectedly intense reactions.

How pictures of bonsai trees incensed our readers

Words generally come first in journalism, images are secondary. Usually. And that’s not entirely fair. A good Image Director will bypass the cliché and opt for the unexpected, to enrich stories in new ways. But when I chose bonsai photos for a story on the hidden life of trees, this approach led to unexpectedly intense reactions.

Why talking is lying

Muslims, bankers, liberals – we use some terms so automatically, we don’t realize they are actually little lies of language. And little lies have a way of turning into big lies.

Why talking is lying

Muslims, bankers, liberals – we use some terms so automatically, we don’t realize they are actually little lies of language. And little lies have a way of turning into big lies.

The solution to just about everything: Working less

For more than 100 years, our workweek kept getting shorter. But since the 1980s, we’ve started working more and more. Why, exactly, is anybody’s guess, because a shorter workweek would solve nearly all the big problems of our day.

The solution to just about everything: Working less

For more than 100 years, our workweek kept getting shorter. But since the 1980s, we’ve started working more and more. Why, exactly, is anybody’s guess, because a shorter workweek would solve nearly all the big problems of our day.