“Livin’ in the moment.”

“It sucks, but we’re going to make the best of it.”

“Just trying to get drunk before everything closes.”

At any other time, these could pass as a bunch of corny T-shirt lines mocking … what exactly? Existential fatigue? State oppression? Prohibition?

But on 18 March, when revellers in Miami spoke those lines as they ignored a deadly pandemic to celebrate their spring break – slapping each other’s bare bodies, puffing away at their shared hookahs, and driving around the city in golf carts casually handing out invites to birthday parties – it was hard not to gasp with shock.

Did they not get it?

Read this story in one minute.

The coronavirus is proving to be a great teacher of human psychology, teasing out our latent racism and xenophobia as well as our innate capacity for great good. But to me, the most fascinating psychological lesson from the pandemic has been the role played by anxiety – or, as seen in Miami, the seemingly bizarre absence of it – in shaping our response to what has been called the gravest humanitarian crisis since the second world war.

In evolutionary terms, the function of anxiety was exactly to protect us from disasters like this. But over centuries, that narrative has changed dramatically. Anxiety has been pathologised, stigmatised, and reduced to a dirty word – something to cope with rather than learn from. So, while paying attention to this primal emotion was once second nature, what we now glorify is just the opposite: rebelling against it and undermining it in a dangerous display of bravado.

From climate change to the coronavirus, this line of thinking has repeatedly pushed us to act in dangerous ways, shutting out those who know better as "conspiracy theorists". This pandemic is offering us an unexpected chance to hit the reset button and repair our broken relationship with anxiety.

How the coronavirus split humanity in two camps

Before city after city started enforcing lockdowns, the coronavirus brought out two sharply contrasting forms of public behaviour. There were those who were anxious about what was coming and furiously channeled that anxiety to protect themselves and others. Then there were others who dismissed it as an overreaction – even an attack on their freedom.

The former camp included the likes of the Twitter user Jason Yanowitz, who quoted an unnamed Italian citizen to serve us a grim warning: "If you’re still hanging with friends, going to restaurants/bars, and acting like this isn’t a big deal, get your shit together." People around the world heroically placed themselves under house arrest to stop the enemy in its tracks. We even had a mini pop culture revolution called #FlattenTheCurve.

In a parallel universe, we had the holiday makers in Florida, the club hoppers in Berlin, and those who thronged to the “lockdown parties” in France and Belgium, nonchalantly trotting out variations of the same bizarre line: “If I get corona, I get corona.”

The cost of this denial was sickening. In Berlin, within two days at the end of February, 26 people who had attended two separate nightclubs in the city tested positive for the virus. The University of Tampa in Florida announced on 23 March that five spring breakers had also tested positive. In both cases, several dozens more were possibly infected without their knowledge.

In my own country India, the prime minister appealed for a 14-hour nationwide curfew on 22 March. But the discipline came undone in the afternoon, when people took part in euphoric mass processions and danced on the streets, as if celebrating a festival, under the excuse of applauding the country’s frontline workers. Some of the scenes were downright unbelievable.

Oh and Elon Musk, hailed as one of the smartest men on the planet, tweeted: "The coronavirus panic is dumb."

Administrations around the world trivialised the threat too. In Italy, for instance, a football match on 19 February involving over 40,000 spectators is suspected to have triggered the rapid spread of the virus in that country. The match was allowed even though Italy had declared a state of emergency on 31 January. Meanwhile in France, as late as 7 March, Emmanuel Macron, the president, and his wife went out to the theatre, saying: "Life goes on. There is no reason, apart from [for those who are] vulnerable, to change our habits."

Elsewhere, Belarusian president Alexander Lukashenko proposed driving tractors and drinking vodka to kill the virus, while Turkmenistan’s dictator Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov ordered smoking it out by burning a local herb.

And despite mounting evidence to the contrary, US president Donald Trump declared that "The virus will not have a chance against us."

The primal role of anxiety

With the advantage of hindsight, we need to ask what explains such behaviour. It is tempting to blame the foolish exuberance of youth, our unfamiliarity with a pandemic this severe, bad governance, or our misplaced trust in medical advances. But what we could really be looking at here is a malfunction of one of the human species’ most reliable built-in shields from danger: anxiety.

For early humans surviving as hunter-gatherers, life was treacherous. Anxiety was the defence mechanism that helped them locate and block out (potential) dangers. It was the tingling at the back of the neck that made them jump and run the moment they heard a rustling in the bushes.

We still experience the remnants of this when standing on a skyscraper and looking down – the height frightens us, even though we know we are perfectly safe. It is an evolutionary reminder of the dangers of climbing tall trees in our primitive days.

According to neuropsychologists, anxiety in modern humans is controlled by the brain’s limbic system, which is "the major primordial brain network underpinning mood [and a] network of regions that work together to process and make sense of the world".

In other words, this is the domain of (among other things) pure survival instinct.

"Anxiety was an extremely adaptive emotion," psychologist Nitasha Borah explains. "If humans didn’t listen to their anxiety, we wouldn’t have made it so far."

How anxiety became a disorder to be treated

But as time passed, we became confused. Anxiety stopped being our friend and came to be labelled as a "disorder" or "disease".

Greek and Latin physicians and philosophers identified anxiety as a medical disorder, but it was not classified as a separate illness between classical antiquity and the late 19th century. The German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin (1856-1926) mainstreamed the study of severe anxiety in manic depression, anticipating the "anxious distress" symptomatic of bipolar disorders in the current bible of psychiatric diagnosis: the DSM-5.

Psychologist Graham CL Davey points out that there has been "a gradual shift in the social ethos surrounding anxiety. This change has been almost contradictory in the messages it sends to us. We’re told anxiety is a legitimate response to the stresses of modern living, and anxiety is almost considered a status symbol that signals how busy and successful we are."

But, in the same breath, we’re led to believe that anxiety is a problem that needs treatment.

In the US, where anxiety is the most common mental illness, addiction to anti-anxiety pills is thought to be potentially more dangerous than the opioid crisis

As Davey explains: diagnostic categories for anxiety problems have burgeoned over the past 30 years, the pharmaceutical industry is keener than ever to medicalise anxiety and sell a pharmaceutical solution for it, and campaigns that increase awareness of anxiety valiantly attempt to destigmatise it – only to help us seek treatment for it.

In the US, where anxiety is the most common mental illness, addiction to anti-anxiety pills is thought to be potentially more dangerous than the opioid crisis. Overdose deaths involving popular drugs such as Xanax, Librium, Valium and Ativan, commonly used to treat anxiety, phobias, panic attacks, seizures and insomnia, quadrupled between 2002 and 2015. In 2015, benzo overdoses accounted for 8,791 deaths, up from 1,135 in 1999.

This is the central paradox of anxiety as we understand it today: if you don’t have it, are you even alive? And if you have it, what are you doing to get rid of it?

Defiance is a way to mitigate anxiety

There is another, simpler explanation for why people behave dangerously during crises: the phenomenon of psychological reactance. "People tend to react in the opposite way to rules and restrictions imposed by forces outside of their control, especially at volatile times. When a lot of things seem out of our control, we exert control where we can," says Borah.

"So you’ll have some people saying, ‘You can ban everything, but I can still choose to party. Even if it is a risk to my health, I choose to assert my autonomy.’ These actions might appear stupid to us, but they mean something to the one who’s performing them."

To make things even more problematic, Covid-19 is the first pandemic in the social media age, meaning there’s a readymade audience for our every emotion and behaviour. This makes appearing in control even more valuable: "Look at me, I’m fine and I’m still partying."

Ultimately, though, acting in ways that defy common sense during a crisis could be a desperate cry for help. According to Borah, people often defend themselves against anxiety or uncertainty by rationalising apparently illogical behaviour. So, you go out and meet friends and "get drunk till everything closes down", and you explain it away by saying there may be no tomorrow.

Anxiety is good. As long as it doesn’t turn into panic

How do we reclaim the power of anxiety for good? First, with compassion. The virus has brought with it the worst kind of prejudice, turning neighbour against neighbour, as we saw in Wuhan. In India – which the World Health Organization has called upon to lead the world in the fight against the coronavirus because of its success in eradicating other deadly diseases – there have been reports of draconian state action, even police violence against medical personnel, under the guise of enforcing curfews. A sudden lockdown has forced thousands of migrant labourers to walk hundreds of kilometres to their homes. Such stories achieve nothing except push an already jittery public into blind panic.

Next, we need to reach back into our memory as a species and remind ourselves that anxiety is not always an obstacle to overcome. As long as it doesn’t paralyse us, we can use anxiety and make it work for us. "Anxiety can help you prepare, take what you are about to do as something important, and put more effort than is strictly required," says Borah.

Of course, the thing about putting more effort than is strictly required is that if it works as intended and actually helps us prevent bad outcomes, it will inevitably appear like an overreaction. But as we are finding out now at an unthinkable price, there’s no contest between overreaction and complacency.

In fact Covid-19’s legacy ought to include how it reminded us that anxiety and overreaction are desirable traits – signs of strong, proactive leadership.

Consider one of the countries where the virus has met the strongest resistance: South Korea. At the time of writing, new discoveries there are at a four-week low, making it a remarkable example for other countries. A single, swift move by the South Korean government is widely credited for these results: its decision to relentlessly test people for the virus.

Covid-19’s legacy ought to include how it reminded us that anxiety and overreaction are desirable traits – signs of strong, proactive leadership

Chastened by its experience during the Mers outbreak, when 16,000 people were quarantined and 38 lost their lives, South Korea has been testing 20,000 people daily for Covid-19 – more per capita than any other country in the world. To support the massive load, it has created a vast network of public and private laboratories, drive-through testing centres, and phone booth-style testing centres where each test takes just seven minutes.

In addition, the South Korean government has taken aggressive action that might be seen as excessive in other democracies, including prosecuting churches for disobeying its guidelines. It has also faced criticism, notably in western media, for its extensive use of surveillance technology to track people for testing.

At a time like this, there are no morally perfect solutions. It is an unfair question whether the infringement of privacy in the South Korean model is more reasonable than the severely curtailed freedom of movement in Italy and France – and increasingly in India, the US, the Netherlands, the UK.

But if you ask me whether an anxious, overactive government is better than a panic-stricken population in the face of an indiscriminate, invisible threat, I know my answer.

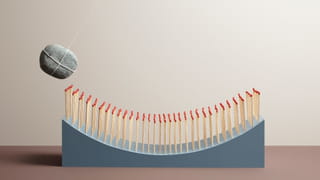

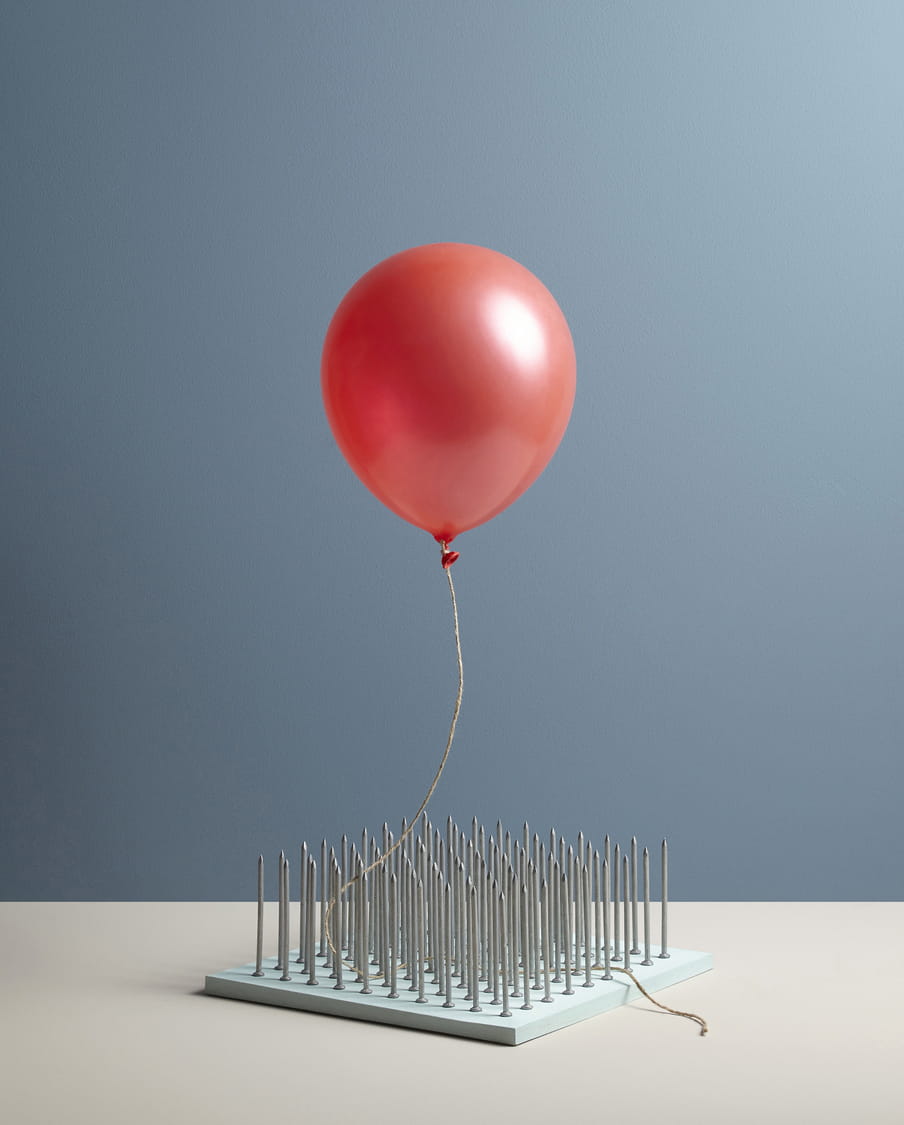

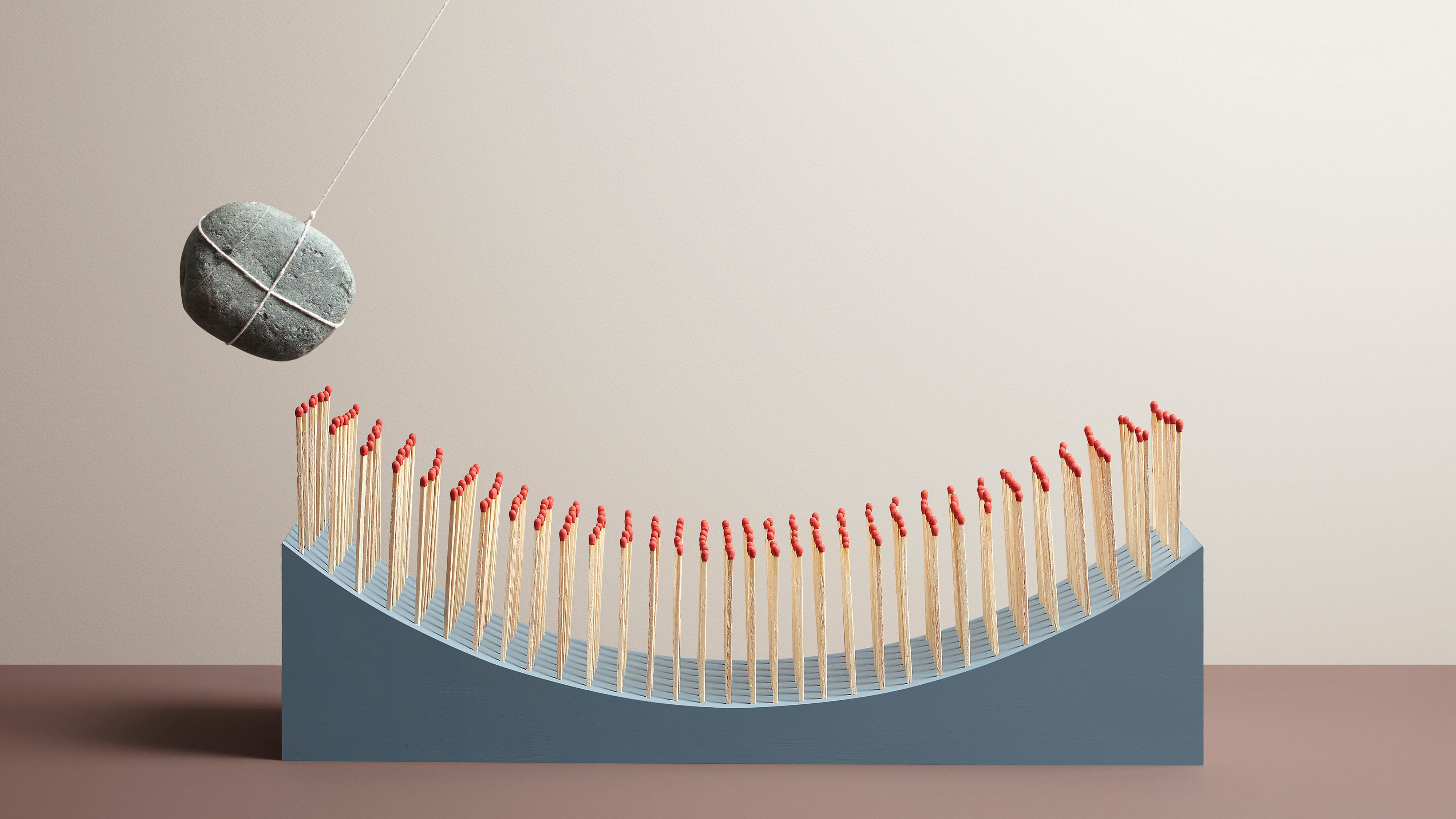

About the images

Photographer Aaron Tilley and set designer Kyle Bean collaborated to create a series inspired by the theme of ‘adrenaline’. The series In Anxious Anticipation shows staged scenes that make the hairs stand up on the back of your neck. The tense scenarios are frozen right before something is about to happen. Something bad. As viewers, we’re anticipating the disastrous event that’s just about to occur – or maybe it won’t, who knows? (Lise Straatsma, image editor)

About the images

Photographer Aaron Tilley and set designer Kyle Bean collaborated to create a series inspired by the theme of ‘adrenaline’. The series In Anxious Anticipation shows staged scenes that make the hairs stand up on the back of your neck. The tense scenarios are frozen right before something is about to happen. Something bad. As viewers, we’re anticipating the disastrous event that’s just about to occur – or maybe it won’t, who knows? (Lise Straatsma, image editor)

Dig deeper

The time has come to take the self out of self-care

While the reminder to care for oneself can lead to improved wellbeing, the idea is increasingly commodified and weaponised against those who are most vulnerable. Here are four problems with our golden age of self-care.

The time has come to take the self out of self-care

While the reminder to care for oneself can lead to improved wellbeing, the idea is increasingly commodified and weaponised against those who are most vulnerable. Here are four problems with our golden age of self-care.