I really needed to pee. It was about 6:30am on a quiet July morning and I had spent an inordinate amount of time waiting to get through customs and immigration at Johannesburg’s OR Tambo International Airport.

As I power-walked in the direction of the restrooms, I saw a queue of women with the same needs curling along a wall, the line growing towards me.

This isn’t going to work, I thought. So instead, I walked past the queue and entered the other restroom. There was only one other person in there, a man with a blond ponytail, who yelled something about me being lost or unable to read.

When I emerged – after washing my face, brushing my teeth and putting lipstick on (I confess, I used the stall with wheelchair access) – the person mopping the floor gawked at me briefly before letting out a shocked, delighted laugh. Not a single urinal was occupied. Outside, the queue for the other restroom had grown even longer.

The proximity, design and availability of toilets in public spaces can reveal many of the uninterrogated ideas that shape our societies, and how we think about people and their rights to space, movement, or even dignity.

If I’d been in South Africa as a child, it would have been inconceivable for me to use the same toilet as a white man, even if I shared his gender.

According to a 2007 study, users of women’s toilets spent an average of 90 seconds, compared to the 40 seconds spent approximately by each user of men’s toilets. Yet, until 1996, British building regulations required that both facilities carry equal numbers of toilets in public places, in addition to urinals in restrooms that were designated as male, which meant twice as many options in male loos, and as a result less time wasted just waiting to pee.

In West Africa, taxi drivers can often be seen peeing on their car tyres while parked outside restaurants and hotels. When a Twitter user in Accra lamented having spotted a driver urinating in public, rather than in the nearby hotel, Ghanaian writer, Kinna Likimani, challenged the underlying assumption that these individuals were simply uncouth. “We assume that folks have [the] same level of access to these hotels,” she wrote. “Often they don’t. Either they’ve been shooed away from similar places before or they sense [they’re not welcome]”.

For vulnerable people living in neighbourhoods where in-home toilets are rare, a bright light mounted above a wall can mean the difference between having to go in a plastic receptacle at night or being able to safely relieve oneself, regardless of the time of day. For some children, the presence of a toilet near their home or school can mean a better chance of living beyond the age of five, or the possibility of continuing their education past puberty.

Then there is the issue of the neat categorisation of toilets into ‘male’ and ‘female’, which, despite being a relatively new concept that serves to legitimise the gender binary, is also often used as evidence that this binary is universal and immutable. As a result of this reversal of logic, many people today think it is unremarkable that there are generally diaper-changing tables in toilets used by mothers, but not in the ones where the only thing standing between a person like me and an empty bladder is a stick figure on a door.

A toilet is just a toilet, until it is not. It can be a simple facility for meeting a basic need, a thing you’ve heard of but have never seen, or a matter of life and death. And this difference – with toilets or almost anything else that impacts on quality of life – depends on the degrees of humanity accorded to people in any particular situation.

Most people would agree that as human beings, we all deserve certain liberties, dignities and possibilities. However, most people also accept, often unquestioningly, that these may not be afforded to everyone, or can be violently stripped away. This is what it means, at its core, for anyone to be ‘the Other’: to have access to only some, or even none, of the things that human beings are understood to deserve.

“Class privilege is real”

In early 2017, I joined a small demonstration designed to raise awareness about the demolition of a fishing settlement in Lekki, a relatively new, fast-developing part of housing-hungry Lagos, the economic nerve-centre of Nigeria.

The demonstrators were all members of the Nigerian Slum/Informal Settlement Federation, many of whom had been forcefully evicted from their own homes or threatened with the possibility in the recent past.

We gathered at an upscale hotel, outside the ticketing booths for a play being put on that night. The show, based on the life of Fela Anikulapo-Kuti, the rabble-rousing musical genius who opposed state violence and championed the rights of the downtrodden masses, had been sponsored by the Lagos State Government as part of its 50th anniversary celebrations. The irony was not lost on the protestors, our flyers reading: “What would Fela do?”.

Unsurprisingly, we were made to leave the premises. The hotel manager, who came down in a disdainful huff, turned away from Mohammed ‘Vagabon King’ Zanna, the slum-based activist coordinating the demonstration, and addressed me: “These people can’t be here. I expect you to understand, even if they can’t.”

On the street, we struggled to get the flyers into the hands of anyone attending the event inside. But later, returning to the hotel on my own, I ran out of leaflets.

With every piece of paper, pressed into an open palm, I delivered a short spiel detailing the most important points: 30,000 people had been violently evicted from their homes, state security personnel had been involved in the demolitions, people had died because they had been shot or drowned. The residents of Otodo Gbame just wanted their land back, and they deserved to keep their homes, to be safe, and to continue to lead productive, satisfying lives.

At the end of that evening, as I sat at the bar nursing a cold drink and a slight headache, I tweeted in a daze: “Class privilege is real.” I was referring to the marked difference in people’s willingness to listen once I was no longer with the group. I also meant the heartbreaking ease with which many of the guests asked questions such as: “Why didn’t they just pack their things and go?” and “Why didn’t they get proper certificates for their land, if they’ve lived there for over 100 years?”

These guests – who were spending more than the monthly minimum wage on one evening of entertainment – couldn’t see that life outcomes were connected to differences in social location, identity, and degrees of alignment with ‘the norm’. In that moment, they failed to recognise that while differences in experience are inherent to the human condition, indignity, discrimination and dehumanisation are not.

Some of the sources of our blindspots are easy to find. When the media in general, and the news in particular, frames certain people as undeserving of compassion or lacking in complexity, they reinforce the largely unquestioned ideas we hold about the rights that such people have to their own lives. They make it possible for us to look away from things that we know people should not experience.

Challenging inherited ways of seeing

In news media, and in much of our popular culture, it’s easy to tell who we are supposed to see as people, and who we’re not. To those who are constructed as human, normal, and worthy, we are encouraged to extend grace, understanding, compassion – even carte blanche.

The opposite is true for those who don’t qualify. They are rarely seen as individuals, but rather always as part of some easily-labeled group. They are the ones for whom any achievement is astonishing, or a lesson in tenacity and grit, while undesirable outcomes are framed as unsurprising, expected. With these people we are primed to be incurious, satisfied that we already know the contours of their lives.

Most of us have inherited ways of seeing one another which are hierarchical, oppositional, and deeply resistant to change. The inevitable result of this way of thinking is that the space between us widens, with the prosperity of some coming at the expense of the devastation of many. But there are alternatives to the narratives that normalise dehumanisation and, as your Othering correspondent, I’m eager to explore them.

Imagine if, instead of stereotyping others, the media enabled us to develop a perspective that sees all people as people, no matter how different from us they may be? What if, instead of framing specific human experiences as superior and exclusively legitimate, we were able to make space for a multiplicity of experiences?

Too many of us have incorrect or incomplete information about people unlike us. Our view of the world is limited by preconceived notions about where people can go or who people can be, how people can live or what they have the right to do. These ideas are received from our societies and reinforced by powerful structures, such as education and political systems, or media makers.

But when we can recognise people’s differences from the so-called ‘norm’ without losing sight of their full humanity, new vistas open up before us. We become free to shift the centre, free to question everything, free to see the world as it really is. To me, this shift in perspective is an important step towards dismantling the boundaries that force us into smaller lives than we deserve, moving us closer to a world where things are more flexible than fixed, with room for adventure, discovery, and surprising possibilities.

When I walked into that toilet that morning, I really just needed to pee. I wasn’t trying to make a point, and I’m aware that it was safe for me to do for reasons which would not necessarily apply to everyone. But as I walked out in relief, with the sound of a small South African man’s laughter trailing me, something, however minute, had shifted in the world, for both of us.

I’m a woman. I peed in the men’s bathroom because it occurred to me that I should be able to go in and out of a public toilet without wasting fifteen minutes in a queue. And nothing happened, because when it comes down to it, a person is a person. Sometimes it’s more complicated than that, but often it’s just that simple.

About the images

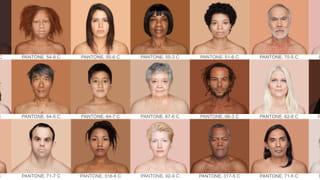

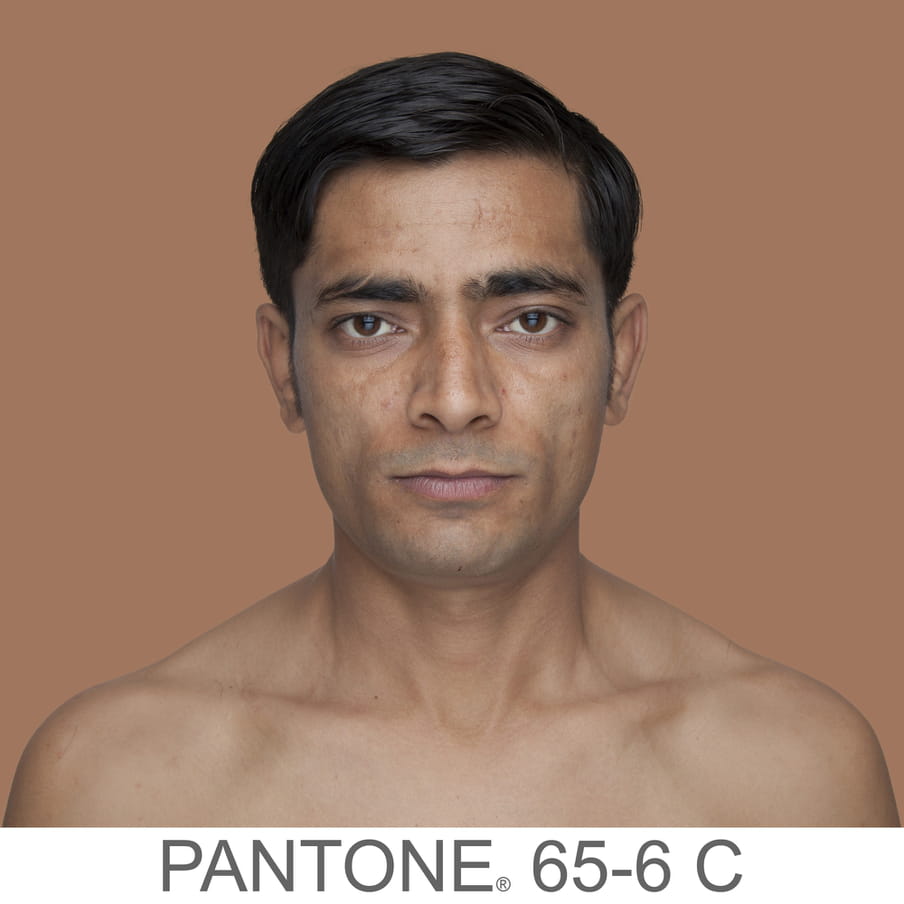

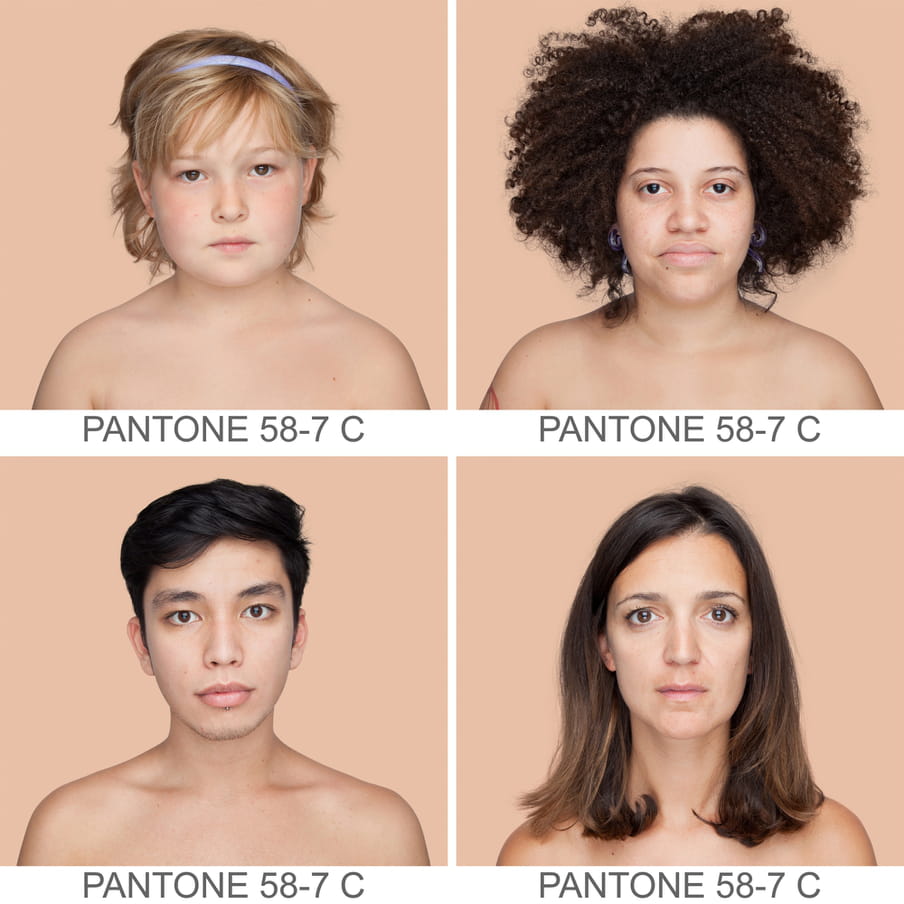

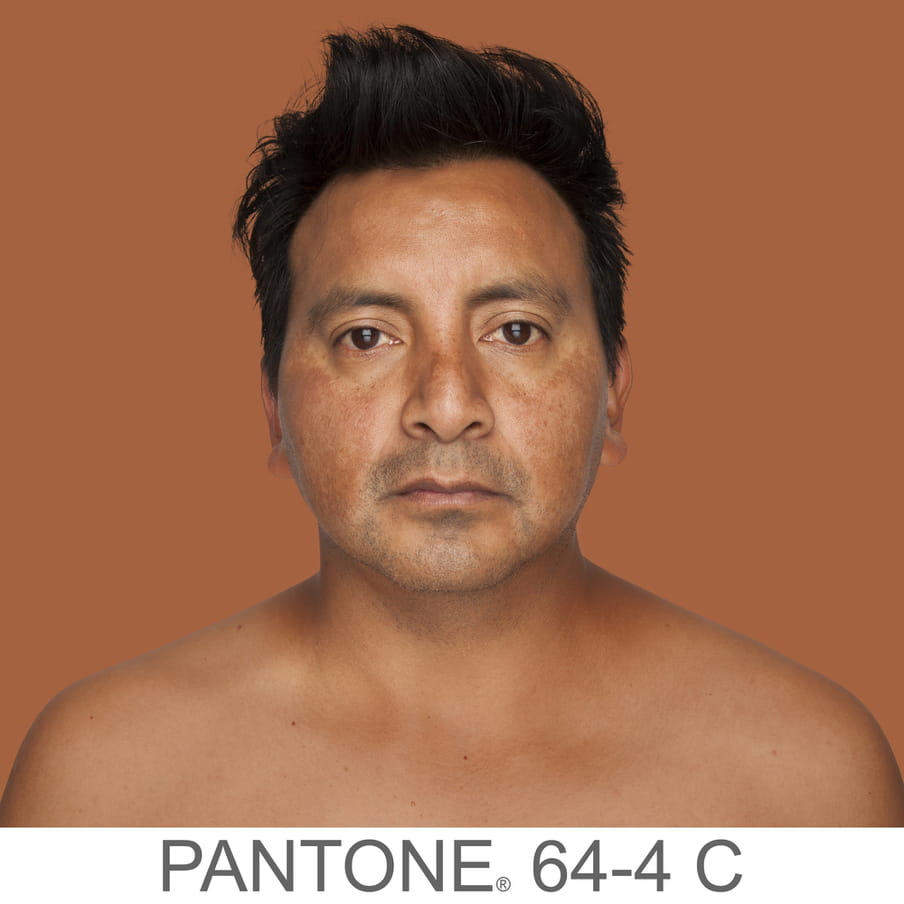

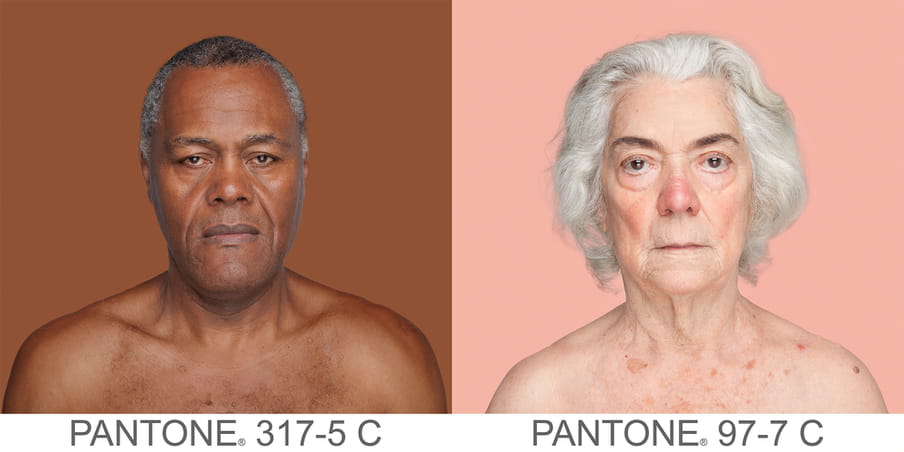

Humanae is a photographic project by Madrid-based Brazilian visual artist Angélica Dass. Humanae seeks to demonstrate that what defines human beings is their inescapable uniqueness and consequently their diversity. The background for each portrait is tinted with a colour tone identical to a sample of 11 x 11 pixels taken from the nose of the subject and matched with the industrial pallet Pantone. This, in its neutrality, calls into question the contradictions and stereotypes related to race. Anyone can volunteer to participate and there is no date set for the project’s completion. Currently, more than 4,000 images exist as part of Humanae. (Lise Straatsma, image editor)

About the images

Humanae is a photographic project by Madrid-based Brazilian visual artist Angélica Dass. Humanae seeks to demonstrate that what defines human beings is their inescapable uniqueness and consequently their diversity. The background for each portrait is tinted with a colour tone identical to a sample of 11 x 11 pixels taken from the nose of the subject and matched with the industrial pallet Pantone. This, in its neutrality, calls into question the contradictions and stereotypes related to race. Anyone can volunteer to participate and there is no date set for the project’s completion. Currently, more than 4,000 images exist as part of Humanae. (Lise Straatsma, image editor)

Stay up to date with OluTimehin:

Join the conversation about Othering

Follow OluTimehin’s weekly newsletter to receive notes, thoughts, or questions on the topic of Othering and our shared humanity.

Join the conversation about Othering

Follow OluTimehin’s weekly newsletter to receive notes, thoughts, or questions on the topic of Othering and our shared humanity.