Mention the concept of "eras" to a historian, and there’s a decent chance you’ll be greeted with a frown and a sigh. The fickle vagaries of human history do not lend themselves to easy categorisation.

Read this story in one minute.

Our own contemporary period is even more difficult to pin down. Titles describing the zeitgeist abound, but none of them definitively define the "era" in which we live.

Is this the era of globalisation, vanishing borders and dissolving nation states? Or swelling nationalism, immigration restrictions and putting the homeland first? Is this a time of multinationals, plutocracy and the 1%? Or startups, crowdfunding and the 99%? Is this a time of revolution, uprising and protest? Or technocracy, indifference and apathy? Is this a time of the sustainable, artisanal and local? Or fossil fuel, mass production and outsourcing?

The answer may well be: it is the time of all these things at once. Even so, the question of the most defining characteristics of our time has gripped me since I first embarked on my study of philosophy, 15 years ago now.

Truth has been the centre of attention for years. But what kind of truth?

My thoughts on the matter mostly revolve around what could be called the most fundamental and most heatedly discussed concept of the past decade – and likely the decade to come: truth.

Some argue that with fact-free politics and fake news running amok, we’ve entered a society that is post truth, but I wouldn’t want to go that far just yet. To me, the better question would be: assuming truth is still with us in some way, what type of truth is characteristic of the times we live in?

Now that, in turn, might sound like a ridiculously general question: truth about what, for whom, and in what sense?

The role that truth plays in politics differs quite dramatically from its role in, say, science. And the type of truth that is dominant in North Korea or Saudi Arabia is very different from the type of truth that characterises a country like the United States or the Netherlands.

Still, certain types of truth can be distinguished that were dominant in our collective thinking for long periods of history. When I say "our collective thinking", I’m specifically referring to western thinking. And when I say "thinking", I don’t just mean the way in which prominent philosophers viewed the world, but also – and maybe even above all – how society as a whole perceived the world around it.

If you look at history from that perspective, which eras of truth lie behind us? I would like to specify three: the premodern era, the modern era, and the postmodern era. From that starting point, I want to ask the question: if it is the case that these eras are behind us, then what type of truth is characteristic of the times we live in?

The premodern era: truth as faith

The history of western thinking has been summarised by British philosopher Alfred Whitehead as "a series of footnotes to Plato". Not because Plato supposedly said all there was to say about the world in a philosophical sense but because he was the first to introduce the distinction that would dominate western thinking about what is "true" and "real" for nearly 20 centuries: the distinction between appearance and reality.

This distinction was based on the concept that the earthly reality around us was merely an illusion, derived from a "pure" reality elsewhere. Truth, the Platonic model essentially argues, is something "supernatural" and "superhuman", in the sense of metaphysical or transcendent. It is beyond the grasp of human understanding.

This distinction has been the foundation of nearly every religious practice that would grow to become a world religion over the past 2,000 years. In that respect, Christianity and Islam in particular are really just mythical variations on Platonic thinking based on the idea that Truth is to be found "out there" – outside human and earthly reality.

To put it differently: Truth is not found in the sensory reality around us, but given to us by a "higher" reality above and outside us. Attaining Truth required a leap of faith – a surrender to the transcendent. Behold the birth of the first era: Truth as Faith.

Life on earth was so hopeless and desperate for most people that there was no reason to think it would ever get any better. The idea that reality on earth was merely an ‘illusion’ offered some comfort

This type of truth was characteristic of the west from roughly three centuries before Christ to 16 centuries after Christ.

The American philosopher Richard Rorty argued that the dominance of this concept could be attributed largely to the miserable living conditions during that period. Life on earth was so hopeless and desperate for most people that there was no reason to think it would ever get any better. The idea that reality on Earth was merely an "illusion" offered some comfort, and the "transcendent" offered hope of an escape, according to Rorty.

The dominant frame of mind, or zeitgeist, of this era was hope for redemption. Although life on earth lacked any prospects, those who had faith could expect salvation.

Consequently, the era of truth as faith was an extraordinarily static period in history. The concept of "progress" was completely unknown, as were concepts like the "mouldability" or "controllability" of life or the natural world. In fact, most people believed that the world had always been the way it was at that very moment – and that it would remain that way forever. You can see this view expressed in concepts like "creation" – foundational to most religions.

This perspective was also reflected in comparable views about social hierarchy: those who were born into poverty would die as poor as their parents. There was no social ladder to climb or descend; the highest attainable goal in life was, in Rorty’s words, "reconciliation with the natural order" – a natural order that had been assigned to the world and humankind.

The modern era: truth as knowledge

This type of thinking was largely abandoned around the late 16th and early 17th century. If I had to describe this major shift in mindset in spatial terms, I would say that truth "came down", so to speak – it descended from "above" to "below" and went from "out of reach" to "within reach" of human beings.

In what we now call the "modern era", truth was no longer viewed as a purely metaphysical concept elevated beyond our grasp, but something tangible – and indeed, physical – in the earthly here and now.

Truth changed from something that was given to something that could be found

A pivotal figure in this shift was French philosopher René Descartes, the forefather of rationalism, who laid the foundation for the idea that the Truth could in fact be known. Logic and reason could be used to comprehend reality and discover the Truth. Truth changed from something that was given to something that could be found. This period brought us objectivity as an ideal, as well as the concept of progress and a mouldable world. Behold the birth of the second era: Truth as Knowledge.

This new type of truth was also accompanied by a new zeitgeist. Hope for redemption gave way to hope for progress. The misery that had seemed so inescapable for centuries was suddenly no longer an established fact. And the idea that society was defined by an immutable social hierarchy imposed from above gave way to egalitarian ideologies that would bring the status quo tumbling down, with John Stuart Mill’s classical liberalism and Adam Smith’s first forays into free-market thinking leading the way.

Reconciliation with the natural order of things was no longer the highest attainable goal; no, comprehending and controlling the natural order was the new objective.

The postmodern era: truth as a construct

Truth as knowledge would remain the dominant worldview in the western world for at least three centuries, until its deconstruction in the late 19th and early 20th century.

Pivotal figures in the gradual dismantling of the idea that the truth could be found included such French thinkers as Jean-Paul Sartre, Jacques Derrida and Michel Foucault, as well as the German thinkers Martin Heidegger, Ludwig Wittgenstein and Friedrich Nietzsche.

Nietzsche actually referred to his work as "philosophising with a hammer", and with good reason: what these thinkers have in common is that they all, in their own way, smashed the belief in a knowable or findable truth to smithereens. Truth, as far as these postmodernists were concerned, is neither given nor found: truth (now in lower case for the first time) is created by humans.

In the postmodern era, truth was neither given nor found: truth – now in lower case for the first time – was created by humans

Their respective approaches differed radically: to Heidegger and Sartre, truth was primarily a product of our consciousness, while Wittgenstein and Derrida primarily saw truth as a product of our language, and Nietzsche and Foucault argued that truth was primarily a product of power relations.

If we were to capture the collective essence of their thinking, then their kindred spirit Rorty offers the most useful summary: "You cannot rise above interpretations and get to facts" (the premodern ideal: rising above the earthly reality and arriving at the Truth), "and you cannot dig down below interpretations and get to facts" (the modern ideal: digging into the earthly reality and arriving at the Truth). Behold the birth of the third era: truth as a construct.

In the same way that the Industrial Revolution and the emergence of modern science helped to bring about faith in Truth as Knowledge, the first world war (and later the second) caused the idea of truth as a construct to gain momentum and take hold.

The first and second world wars fostered an enormous distrust of Truth with a capital T. The deconstruction of Truth initiated by postmodern thinkers aimed to undermine its mobilising power: humankind had to be "liberated" from all those false authorities that had laid claim to truth over the centuries.

Where premodernity was characterised by hope for redemption and modernity by hope for progress, postmodernity was characterised by scepticism about both. Reality was parenthesised and the "end of history" proclaimed.

At the same time, there was a huge surge in faith in the power of individuals to make their own reality. If truth was a construct, then you could also shape your own truth – and thus your own life – according to your own preferences.

The ideals of freedom of choice, self-creation and self-fulfilment took the place of redemption by and knowledge of the Truth. Not only did truth become a construct but, for the first time ever, life also became a style.

Reconciliation with "the natural order" (premodern) or control of "the natural order" (modern) became obsolete, because, in fact, there was no such thing as a natural order. Creating one’s own personal order (postmodern) was the ultimate objective from that point on.

Are we in a fourth era?

Obviously, scientific research also took place in the premodern era; faith in transcendence never vanished entirely in the modern era, and the postmodern era did not actually herald the end of history. There are no firm boundaries between the eras; at most, it could be stated that a certain way of thinking is slightly more characteristic of one era than another.

That said, would it now be possible to state that we are in a new era? Have we ended up in what could be referred to as post-postmodernism?

There are plenty of arguments that refute such an assertion. Politics aren’t exactly enlivened by great narratives these days, and distrust of all sorts of authorities is by no means a thing of the past; self-fulfilment is still seen as the supreme ideal in large parts of the western world, and irony as a default attitude is widespread.

Still, I would dare to argue that we have indeed entered an era of a new type of truth. The era of truth as a product.

Post-postmodernity: truth as a product

This type of truth can trace its roots back to postmodernism. This worldview was the philosophical soil in which the ideal of the free market – not the variant proposed by Adam Smith, but the free market of Milton Friedman and Ayn Rand – flourished and became popular.

For, if truth is not found but created, and only the subjective individual can lead that process, then – the reasoning goes – the free market is the only way to an "ideal" society without a guiding authority leading it. The idea of a "common interest" that was still prevalent in the modern era was exchanged for the "sum" of individual interests. In this worldview, the free market would lead to a perfect equilibrium, without having to be guided by a constructed ideology originating from a false authority.

Neoliberal free market thinking started out as a deconstruction of ideology and authority, but, despite its origins, grew into an ideological dogma in its own right, leading to a far-reaching economisation of our worldview.

Moral and ontological dogmas were replaced by economic criteria. No one believed in Truth, Knowledge and Morality with a capital letter anymore; they were supplanted by the so-called "neutral" concepts of productivity, efficiency and return on investment.

In politics, healthcare, education, science, media and the arts: economic criteria became the measure of all things in every aspect of society.

Now, citizens are consumers, patients "shop" for their healthcare, students "invest" in their academic "career", immigrants are "fortune seekers" or "cheap labour", the elderly are dubbed "growing expenses", artists have to be "creative entrepreneurs", and the gross national product is the godly measure of our collective well-being.

The commercialisation of our information

This economisation of our worldview resulted in the commercialisation of society. A crucial aspect of this process was the commercialisation of our information supply. Even our most important sources of information, from news media to education and research agencies to, more recently, search engines and social networks: all of them became increasingly based on commercial logic. Coverage, market share and profitability became the gauges used to measure success.

Just as Big Oil, Big Food, Big Pharma and Big Banks would dominate the oil, food, medicine and financial industry, Big Media would take hold in the ‘information market’

From the 1980s onwards, this commercialisation of our information supply was accompanied by a wave of mergers and acquisitions. Just as Big Oil, Big Food, Big Pharma and Big Banks would dominate the oil, food, medicine and financial industry, Big Media would slowly but surely take hold in the "information market".

Exact figures on market shares are difficult to pinpoint, but at this point in time, it is certain that the majority of all news media, TV and radio broadcasters, film studios, publishing houses and websites that produce the news, TV and radio shows, books, magazines and films that feed and fabricate our worldview can be traced back to no more than 30 major multinationals that are unprecedentedly vast in size – collectively, the represent over $300bn in annual revenues.

A crucial parallel trend was the professionalisation of communication. The phenomenon of public relations became an institutional feature. Over the course of a few decades, it would grow to become one of the biggest and most influential industries in the world; the advertising segment alone accounts for more than $500bn a year.

Communication strategists, PR experts, spin doctors, marketeers and advertisers became the all-powerful architects of our information supply. Nearly all major flows of information – from news to politics, from science to art – were subjected to the laws of public relations: aligned with target audiences and assessed on the basis of reach and revenues.

The economisation of our worldview, the market-based reframing of society, the commercialisation of information and the professionalisation of communication are the four pillars on which the new era rests: the era of truth as a product.

Truth is no longer given (premodern), found (modern) or created (postmodern), truth is sold.

Or, to rephrase it: we went from the revelation, to the discovery, to the construction, to the production of truth.

Truth as a way to satisfy a need

As things stand, it is difficult to make a firm distinction between truth as a construct – which characterised the postmodern era – and truth as a product, which I see as the defining characteristic of the times we live in.

Both ways of looking at the world can trace their philosophical origins back to the idea that truth primarily is a matter of how you explain the world – a matter of perspective, as Nietzsche would say. In that sense, PR and marketing are distinctly postmodern phenomena: they are founded on the realisation that what people assume to be "true" is not derived from some transcendent source or factual basis, but is instead a matter of how the world is "perceived".

However, there is a difference between the kind of mouldable truth that we have come to call postmodern, and the malleable truth that surrounds us now. Truth as a construct originally was conceived as a way to liberate mankind from false authorities and the universal pretensions of Truth with a capital T – in order to allow the individual free rein for self-creation.

Truth as a product, however, serves a very different purpose: it seeks not to liberate us but to satisfy our needs.

In other words, everything we do or create these days is based on the logic of a product. Whether we are participating in politics, providing information, teaching, doing research or creating art: everything is assessed on the basis of which need it satisfies.

Consuming your own opinion

Politics, for example, is not about "convincing as many citizens as possible to embrace certain ideals to serve a common interest"; it’s about determining, formulating and implementing what a certain segment of the electorate (the "target group" or "electoral demographic") thinks and wants.

Or, as the renowned Dutch sociologist Willem Schinkel once put it so succinctly: the goal is "to have voters consume their own opinion". It’s no coincidence that we decide how to vote in a way that bears a strong resemblance to how we choose a washing machine: by filling out a voting compass and picking the candidate that comes out.

Most likely: the one that we would like to "have a beer with".

Our information supply follows the same logic. Google, for example, was founded as a search engine based on the modern ideal of unlocking and providing access to all the information in the world, but by now the company has evolved into its post-postmodern counterpart: a information broker tailoring its results completely to the needs of the "information consumer" as determined by algorithms and consumer search behaviour.

The result: someone who has been profiled as "politically engaged" will see results featuring revolutions and protests when they Google a word like “Egypt”, while someone deemed a "hedonistic consumer" will see summer holidays and seaside resorts.

The same general principles apply to how news is generated in today’s media. News is not "featuring specific events and trends based on an underlying concept of social relevance", but tracking and reflecting on "what people are talking about" in order to align the news reports with the interests and needs of the "target audience".

For the same reasons, education is less about on conveying knowledge that has inherent value, and more about aligning knowledge with the needs of the job market for which the student is being trained. Science is increasingly moving away from research to discover fundamental insights and towards research to benefit economic returns. And art is less inclined to undermine established concepts and increasingly likely to seek alignment with the existing interests of the intended target demographic.

In other words, where truth as a construct was still essentially emancipatory and liberating, truth as a product is predominantly a way to agree with ourselves.

Also known as: bubbles.

Truth without a reason why

The absence of a liberating, emancipatory core is, in my view, the most important characteristic that distinguishes the type of truth endemic in our time from the types of truth that preceded it. All those prior truths did seek to be emancipatory or liberating.

Truth as Faith aimed to free people from an unchanging world plagued by disease and poverty by envisioning a transcendent world that offered the prospect of redemption. Truth as Knowledge aimed to liberate people from the submissiveness and passivity that accompanied this faith in transcendence by envisioning a knowable, makeable world where progress was possible. And truth as a construct aimed to liberate people from the destructive forces of universalism and utopianism that had accompanied faith in Truth with a capital T by envisioning a deconstructed world in which the individual would be in control.

But what does our truth aim to achieve?

Our truth seeks neither redemption nor progress nor change, only satiation

What does truth as a product want beyond satisfying our needs – ad infinitum?

You could say: our truth has taken on a new form, but without a new goal. The aim is neither redemption nor progress nor change, only satisfaction.

I could try to explain exactly what I mean by that, but a sketch by the brilliant US comedian Bill Hicks (sadly no longer with us) does it far better.

In the sketch, Hicks encourages all the advertisers and marketers in the audience to consider suicide. And he means it, too; he keeps saying: "Really, there is no joke coming, kill yourself." The comedian ingeniously shows what marketing is by applying it to his own message: "Do you know what Bill’s doing? He’s going for that anti-marketing dollar, that’s a good market!"

"No," Hicks replies angrily, "I’m not doing that, you scumbags!" To which the marketer responds: "Ah, he’s going for that righteous indignation dollar! That’s a good market. He’s very smart." And so on.

This sketch incisively shows that "truth as a product" really has no philosophical core: truth is whatever sells. It turns politics into a "pitch", information into a "format", art into a "concept", education into a "formula". Not to convince, to inform, to prompt people to think or learn, but to satisfy.

Herein, I think, lies the essence of our era. It explains why there are almost no fundamental ideological differences between political parties, except for how they calculate what a household will be able to spend next year. It explains why schools and universities have become diploma factories in search of the highest score in the rankings. It explains why solidarity is crumbling and short-term profit reigns supreme.

And it explains why 80% of people (in the west) are so satisfied with their own lives, while an equally large percentage are so concerned about where society as a whole is going. Our personal needs are more than satisfied, but we hardly have any idea to what end.

This piece first appeared on De Correspondent. It was translated from the Dutch by Joy Phillips.

About the images

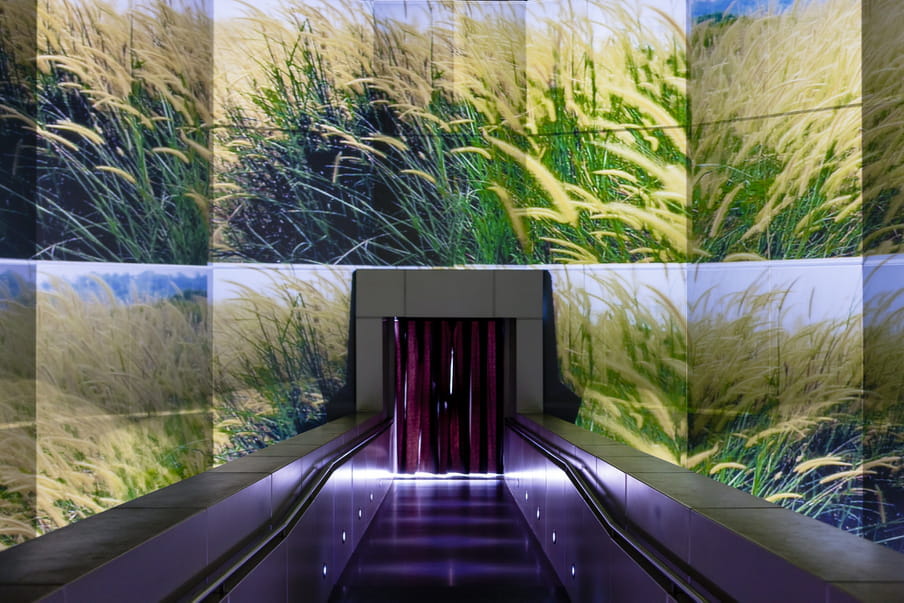

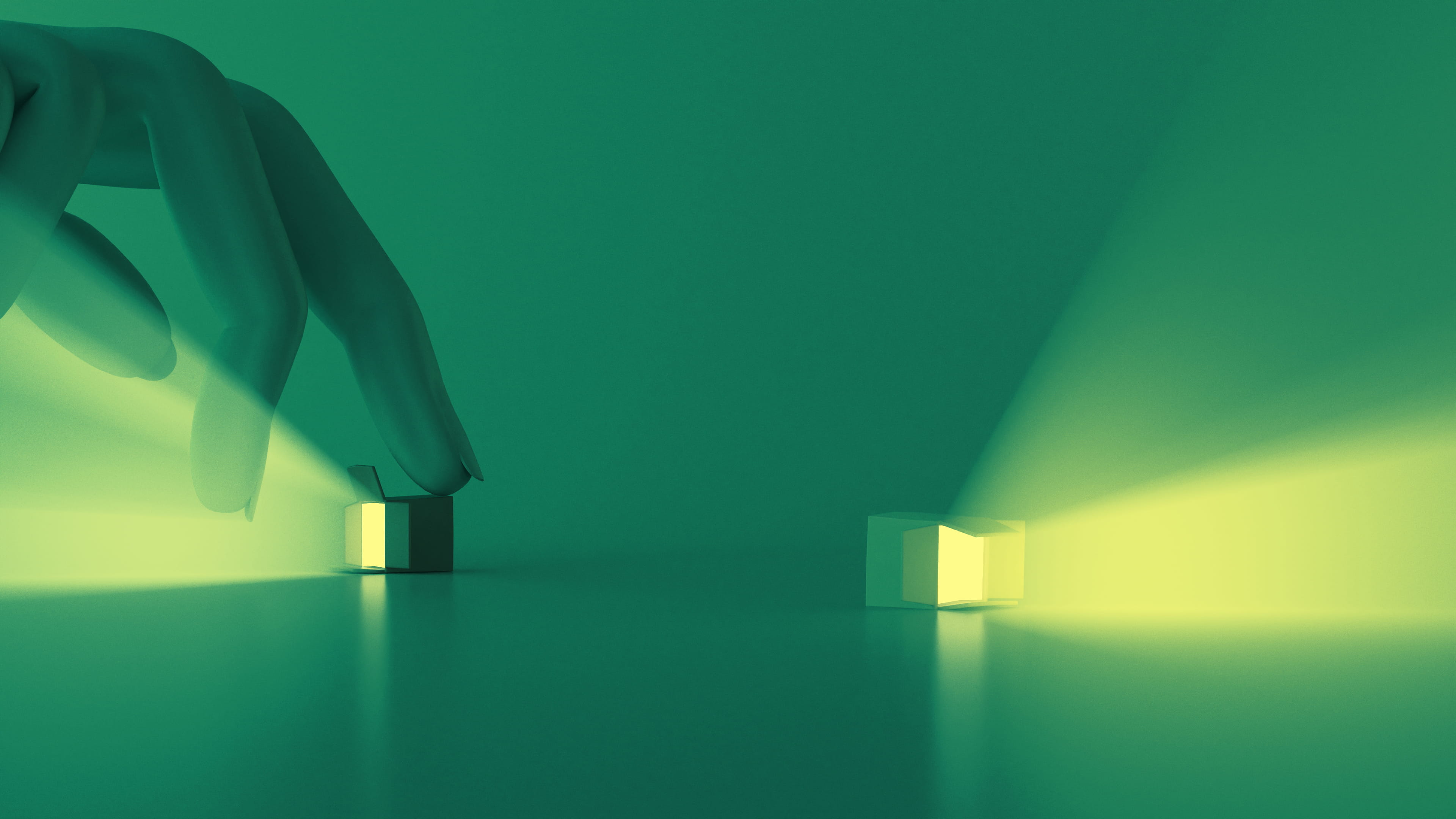

The photos in Theo Derksen’s series Disneyfication, which was over 20 years in the making, are rather confusing at first glance. Strange differences in sizes and scale make you blink once or twice, only to discover strange collisions between reality and the strangely oversized, grotesque commercial images. Disneyfication confuses us on where the real begins and the fake ends. This long-term study of metropolises, which includes Bucharest, Berlin, Egypt, Tokyo, Dubai, Chongqing, Shanghai, Beijing, Singapore and Las Vegas, showcases the intrusive, overpowering effect of these commercial images. (Lise Straatsma, image editor)

About the images

The photos in Theo Derksen’s series Disneyfication, which was over 20 years in the making, are rather confusing at first glance. Strange differences in sizes and scale make you blink once or twice, only to discover strange collisions between reality and the strangely oversized, grotesque commercial images. Disneyfication confuses us on where the real begins and the fake ends. This long-term study of metropolises, which includes Bucharest, Berlin, Egypt, Tokyo, Dubai, Chongqing, Shanghai, Beijing, Singapore and Las Vegas, showcases the intrusive, overpowering effect of these commercial images. (Lise Straatsma, image editor)

Not a member of The Correspondent yet?

The Correspondent is a member-funded, online platform for collaborative, constructive, ad-free journalism. Choose what you want to pay to become a member today!

Not a member of The Correspondent yet?

The Correspondent is a member-funded, online platform for collaborative, constructive, ad-free journalism. Choose what you want to pay to become a member today!

Dig deeper

All lies matter: the gift of the Pro-Truth Pledge

Just as I was beginning to despair that facts in politics had become fiction, a member gave me hope.

All lies matter: the gift of the Pro-Truth Pledge

Just as I was beginning to despair that facts in politics had become fiction, a member gave me hope.