Imagine a powerful person. The prime minister of a rich country, say, taking the stage for a press conference. Think of the voice, the dress sense, the way a prime minister speaks and sounds. Who do you see in front of you? Let me guess.

A man in a suit.

Read this story in one minute.

This is our reflex, our stock idea of a prime minister. It’s an image that plays tricks on many female politicians. Take Senator Elizabeth Warren, a prominent candidate in the Democratic primaries to select a challenger to Donald Trump, the US president, in elections in November this year. After a promising start in autumn 2019, Warren’s campaign has been plagued by loud speculation about her "electability". She’s a woman, after all.

According to Warren, her rival Senator Bernie Sanders told her during a private conversation in 2018 that a woman can’t win in 2020. It’s a claim that Sanders has denied, but the grounds for such opinions are easy to find. In the 2016 presidential race, Hillary Clinton fought Trump in a tough, often sexist campaign. For all her political experience, the word went around that a woman was not "presidential" and hence not "electable". The same assumptions have hurt Warren’s campaign.

Governments in Hungary, United States and Brazil are led by macho misogynists. In New Zealand, the opposite happened

Is it credible in 2020 that women are still not electable to the highest level of power? If you follow the news, you’ll understand the roots of this question. Trump won in 2016 despite – or perhaps, thanks to? – numerous accusations of sexual misconduct and an audio recording of his infamous "Grab ’em by the pussy" comment during a tour of a television studio in 2005.

Not that Trump is by any means the only unreconstructed male to win power in recent years. Hungary and Brazil also chose macho misogynists as heads of state. Better a sexist bastard, it seems, than a woman.

In New Zealand, the exact opposite happened.

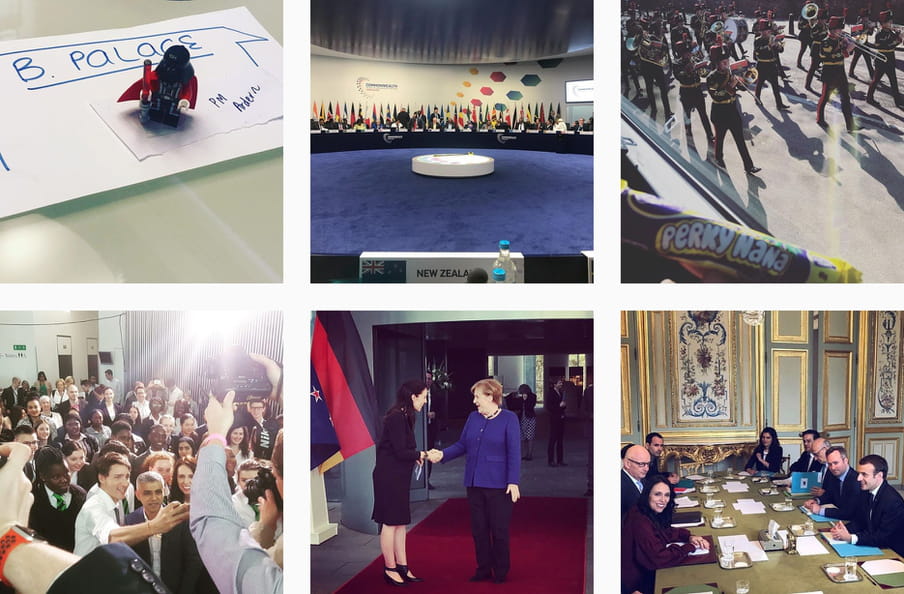

Since 2017, the New Zealand government has been led by a woman who is still (until July) under 40 years old. Ardern’s victory can be compared to other recent political insurgents Barack Obama, Justin Trudeau and Emmanuel Macron.

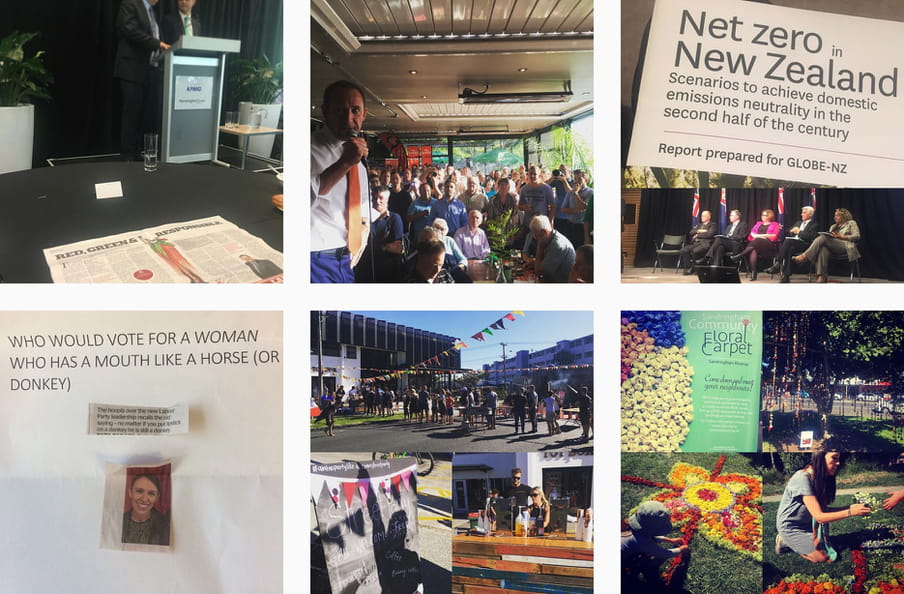

It is a measure of international interest that "Jacindamania" has entered the political lexicon. At the same time, however, the same political climate has rained hatred upon Ardern. Her personal style has upset millennia-old ideas about men, women and power: ideas made visible by the sexist reactions which follow her.

The phenomenon of New Zealand’s third female prime minister shows how the prevalence of these ingrained cultural ideas and, thanks to Ardern and others, how such thinking can shift.

Who is Jacinda Ardern?

Born in 1980, Jacinda Ardern was recruited to New Zealand’s Labour Party at the age of 17 by a politically active aunt. She studied political communication and served as president of the International Union of Socialist Youth. Her career includes spells as a researcher for New Zealand’s first female prime minister, Helen Clark, as well as Britain’s Tony Blair.

A few months before elections in 2017, when the Labour party was low in the polls, its then-leader Andrew Little asked Ardern to take his place. Legend has it that Ardern rejected the job seven times, doubting her own ability. When she took on the role, Labour’s fortunes rose rapidly in the polls.

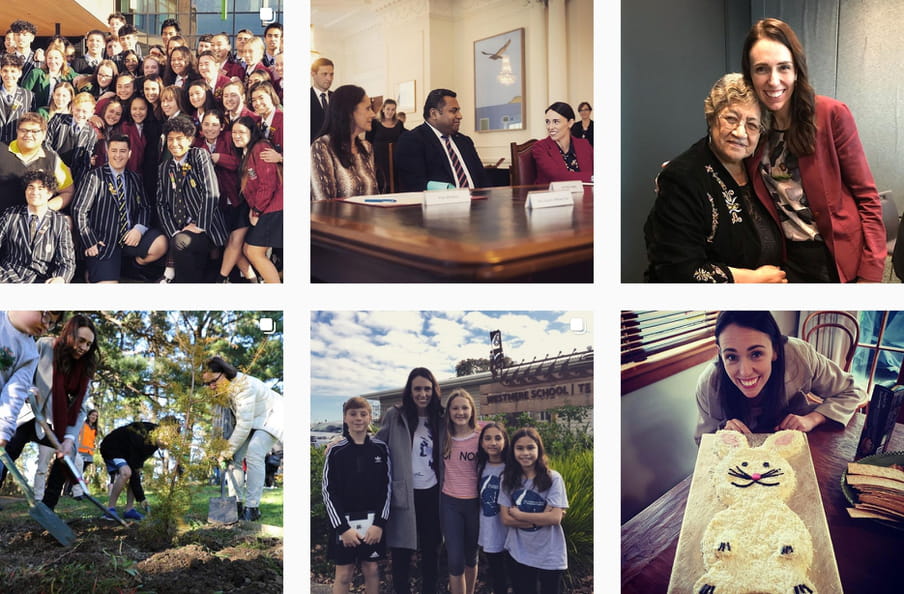

On taking office as prime minister, Ardern – a woman in her 30s who likes wearing dresses, laughs often, and whose speeches are full of jokes at her own expense – was often viewed with scepticism. Was she more than just a pretty face? She was.

An outspoken progressive helmsman

New Zealand had found a distinctly progressive political pilot. Ardern took steps to remove abortion from the penal code, spoke sensitively to her country’s raw colonial history, and appointed a record number of Māori people to positions in her government, although Ardern has recently come under criticism from the Māori community.

In 2019, parliament adopted an historic Zero Carbon Act with cross-party support (and only one vote against), making New Zealand among the first countries to enact into law climate targets from the 2015 Paris Agreement.

Another progressive landmark is her "wellbeing budget" , born of her conviction that a country’s success should be measured not only by wealth, but above all by the wellbeing of its inhabitants. Although New Zealand is rich, says Ardern, its statistics on suicide, domestic violence and child poverty are frightening.

Rather than focus on financial criteria alone, the state budget aims to increase wellbeing. Record sums have been allocated to mental healthcare, poverty alleviation, and the transition to sustainability. Economic growth alone does not make a country great, Ardern argued, “So it’s time to focus on those things that do.”

Her message is that people depend on one another – not on money, numbers or achievements. As if to make her point again, Ardern became only the second head of government to give birth during her term in office. She took six weeks’ leave after her daughter’s arrival, less than a year after taking office, then returned to work while her boyfriend, a well-known TV presenter, took on the role of a housefather. The public followed the young family on Instagram.

An example of moral leadership

Ardern’s political instincts were tested on 15 March 2019 by massacres at two mosques in Christchurch, where an Australian gunman killed 51 people and wounded another 50. Before he opened fire, the killer published a long racist manifesto of extremist ideas, before filming the attack and streaming it live on Facebook.

Ardern swiftly condemned the attack as an act of terrorism, while demonstrating wholehearted supported the bereaved Muslim community. “They are us,” she said in a widely acclaimed speech, followed within a month by a ban on semi-automatic weapons. By refusing to speak the name of the perpetrator, she refused the gunman the fame that he sought.

Photographs of Ardern dressed in hijab and hugging bereaved relatives were shared and published around the world. Praised for her solidarity and empathy, her response prompted speculation that she may have been considered as a contender for the Nobel Peace Prize. Here was a head of state who covered her hair as a mark of respect for Muslims. An anti-Trump!

So this is how human power could look. Finally, something else.

Too good-looking for a prime minister

To her critics, Ardern’s political ideas are not substantively different from those of her Labour predecessors. It’s her personal style and human warmth that explain Jacindamania: her party received record donations, volunteers rallied to support her, and media attention flooded in.

How to explain this "Jacinda Effect"?

Some commentators point to Ardern’s positivity and frankness as key to winning people’s trust. Others dismiss Jacindamania as a fad, a momentary infatuation with her youth and good looks. A political rival doubted if Ardern had the political ideas or intellect to lead her country. Another commentator described her popularity as a kind of political stardust, which wouldn’t last. Politicians must be able to do more than smile and wave, carped another. Ardern had to prove, jibed an opposition party leader, that she is more than lipstick on a pig.

In essence, opponents did everything in their power to exploit Ardern’s youth, gender and appearance by portraying her as the stereotype of a superficial bimbo.

The media have been similarly preoccupied by her appearance.

In an hour-long broadcast, television interviewer Charles Wooley ignored her policies and ideas, but emphasised how attractive he found the prime minister. When, he asked, was the exact date of her child’s conception: was it during the campaign? He asked only one vaguely political question: “How does a nice person like you end up in the dirty world of politics?” It is hard to imagine a male politician being questioned so complacently, as if Ardern were Little Red Riding Hood venturing into the dark forest.

Predictably, when Ardern isn’t too attractive, she is portrayed too ugly. Her prominent front teeth are regularly caricatured by comparing her face to a horse. A recent social media campaign, #TurnArdern, urged people to turn face-down all the publications which had featured Ardern’s face on the cover. Followers of the #TurnArdern movement posted films on social media in which Ardern’s face disappeared from the windows of newspaper kiosks and shops. The prime minister appeared too often on the front pages, explained the man who launched the campaign: he wanted “a prime minister, not a fashion model”.

Is Ardern too handsome, or too ugly, or too visible? Or are the people who make these complaints simply uncomfortable with the image of a powerful woman?

It’s not about the substance

Of course, any politician in a healthy democracy will face criticism. But the censure which Ardern evokes is often and emphatically not related to the content of her policy. In fact, it serves to divert attention from issues of substance as a way to avoid discussion.

As long as you can whine about a politician’s teeth, clothing, voice, wrinkles, or tits, you don’t have to pay attention to her arguments.

Such tactics may seem contemporary, but they follow an age-old historical pattern. Since time immemorial, women who raise their voices in public – and indeed in politics – make themselves unpopular with men who believe the word is theirs.

Consider Warren, who was silenced in the Senate when she tried to read a letter from Coretta Scott King, Martin Luther King’s widow. When male colleagues, including Sanders, read the same letter, they were allowed to speak.

Mary Beard, a British classicist, cites this incident in her 2017 book Women & Power, a history of misogyny from Athens and Rome to today. She begins with an account of Homer’s Odyssey, in which Queen Penelope, wife of Ulysses, is silenced in public by her newly grown-up son because “speech is a man’s business”. To Roman orators, high (female) voices expressed "cowardice". For too many famous novelists, female voices resembled the mooing of cows or the braying of donkeys, sounds which polluted language.

Sharp, too high, unpleasant – the voices of female politicians or leaders would have ‘no authority’

Beard’s book describes a serial smear campaign against the female voice. She shows how prevailing ideas about eloquence and rhetoric are rooted in a classical tradition which dismissed female voices as an aberration. To this day, women are much more often said to be squeaking, whining, squawking, screaming or cackling. Or that their voices are “just uncomfortable” to hear. Like Warren’s, described by a journalist as "unbearably shrill".

This same antique prejudice is directed at Ardern. After her impressive response to the attacks in Christchurch, when she promised never to pronounce the perpetrator’s name, Australian TV presenter Sam Newman tweeted: "Thank heavens NZ prime minister said she will never mention the name of the terrorist. How grating is her accent?" The trick is to avoid listening to Ardern’s message by complaining about the voice bringing the message.

How to be taken seriously? Imitate a man

Authority is not innate. It’s something we grant or deny to each other. It’s cultural. It’s not true to say that a woman’s voice can’t have weight, argues Beard, only that we haven’t learned yet to give that weight to women’s voices.

How do you gain authority as a female politician? The standard tactic is to imitate a man.

Before winning the UK general election in 1979, Margaret Thatcher, who became Britain’s first female prime minister, was trained to lower the register of her speaking voice because her natural pitch was an obstacle to political success. You can hear the difference between before and after.

But it’s not the female voice alone that stands in the way of being taken seriously. It’s a more general conception of womanhood, with everything it implies. Charm, dress sense, performance, tone – all are potential pitfalls for female leaders, more than for their male peers. As the novelist Margaret Atwood wrote: "Politics is doubly hell for women. Not only do you have to have a position, you have to have a hairstyle."

There is a magnifying glass on their appearance, including choice of clothing, and anything that stands out is risky

In today’s mediacracy, image and appearance carry more weight than ever before. For women, that weight is a heavier burden. Visual media functions like a magnifying glass to focus attention on their appearance and choice of clothing. Anything that stands out – or deviates from the (male) norm – can be risky. Every feminine accessory draws media commentary.

Not surprisingly, many female leaders opt for a masculine look, as close as possible to the traditional power dressing: the man’s suit. Think of Angela Merkel and Hillary Clinton, with their dependable trouser suits. But beware! A female politician in a suit can’t go too far with such manly traits. When Warren was seen ordering a beer, she was publicly ridiculed: did she really believe this one-of-the-guys behaviour would convince male voters?

If, on the other hand, a woman politician appears too feminine, the reflex criticism is that she does not radiate power and won’t be taken seriously. French minister of housing Cécile Duflot was greeted in parliament by howls and whistles when she arrived to speak wearing a (rather chaste) floral dress. She made herself understood only with difficulty.

Too cold or too loud

As with dress sense, so too for behaviours. A female politician has to strike a precarious balance between preconceptions of feminine and masculine.

The difficulty is evident in the example of former British prime minister Theresa May. On taking office, she was labelled an "Ice Queen", stubborn and incapable of compromise. In contrast to the cliché of intuitive, warm womanhood, May was nicknamed "Maybot" because she betrayed so few emotions.

The thematic link in these labels is suspicion of a "fake woman". On the other hand, May was "just not man enough". In her cautious approach to Brexit, she missed the stereotypically male qualities of leadership. Her approach was hopelessly "feminine", meaning hesitant. Of course, such criticism was a strong motivator for May not to show emotions. Women who show emotion are deemed to be weak, as she observed after her resignation.

Nicola Sturgeon, the Scottish First Minister, confronted similar dilemmas. Initially, she recalls, she adapted to the (older) men around her by adopting a more aggressive, confrontational style. Recently, she has let go of that macho posture. Her style of dress is more feminine, and she has dared to show vulnerability, even speaking openly about her miscarriage.

With rare candour, Sturgeon has acknowledged her sense of impostor syndrome: a belief that you do not deserve your position, can’t really do the job, and will soon be exposed as an incompetent fraudster. Such doubts are only human, argues Sturgeon. In her view, to acknowledge them is an expression of modesty that everyone should cultivate – not least people in positions of power.

The Ardern strategy

Ardern stands out because she doesn’t follow any of the recognised or standard strategies for women in politics. She wears dresses, skirts, prints, colours, and striking jewellery. She smiles often and doesn’t seem to make any effort to lower the pitch of her voice. Instead of "standing her ground" or seeking emphatic confrontation, her attitude often appears friendly, humane and approachable.

Rather than adopt a stance as ‘her own man’, Ardern is friendly, human and approachable

An example: on social media, Ardern shared a personal note of encouragement which her mother had placed in her bag on election day. The effect was to share an endearing image of herself, rather than a portrait of power. During her maternity leave, she didn’t hesitate to announce a new economic support package for families living in poverty via a Facebook video from her couch, with her 10-day-old daughter in her arms.

Her conception of authority is so different from the usual caricatures that it can appear as if Ardern doesn’t care about authority at all.

Instead of donning her political armour, she has spoken publicly about her nervousness and – like Sturgeon – her own experience of impostor syndrome. When attacked or taunted, she responds with self-mockery. To the recurring remarks about her teeth, notably a suggestion that she wears dentures, she responded in a tweet: “I’ve said it before – surely if you were ordering teeth, you wouldn’t get them in size extra large.”

Rather than vaunt dossiers of knowledge or expertise, Ardern chooses time and again to describe her "intuitive" way of working. She rarely mentions her university studies in political communication: "I am no scholar ... I have always felt like my political views and drive came from my gut rather than a textbook." She claims to act mainly from "instinct" and by doing "what feels right".

These choices – whether strategy, or simply candour – are intriguing. Besides a readiness to take the chance of devaluing knowledge, Ardern also stresses the role of intuition at the risk of losing credibility. Intuition is most often associated with women, a feminine trait aligned more closely to emotion than to reason. Most of us, at least traditionally, don’t attribute such characteristics to people in power.

On to a different kind of power

Ardern challenges centuries-old ideas and status and power. She constantly does things that are traditionally not done for a leader. A lawmaker but a rule-breaker, she is willing on occasion to undermine her own authority – and seems to get away with it.

Just as Thatcher often carried a lady’s handbag – hence the term "handbagging" as shorthand for her belligerence to obstructive colleagues – so Ardern has succeeded in transforming another symbol of femininity into a statement of feminine power: her child.

The fact that Ardern operates with vulnerability, empathy and an emphatically intuitive approach is hopeful

For centuries, motherhood kept women away from public life, confining them to the domestic domain. In contrast, Ardern took her infant to a meeting of the United Nations, where the baby sat on her boyfriend’s lap while its mother took the podium to deliver a powerful speech. Images of this affecting scene were shared around the world.

To operate as she does – with vulnerability, empathy and an emphatically intuitive approach – Ardern has broken a mould. Her example is hopeful. It shows that ingrained ideas about women and power, and what power can look like, are in flux. Even in an era of persistent, rising sexism.

Whatever you may think of her policy, Ardern’s leadership deserves admiration. "That idea that power cannot be accompanied by notions of compassion and kindness and empathy," Ardern has said. “That’s something that I refuse to accept.” Amid recent hardening in political attitudes around the world, this prime minister is helping to create space for a different kind of power.

And that is a space from which leaders of all genders can benefit.

Correction: Ardern is the third female prime minister of New Zealand, not the second.

This piece first appeared on De Correspondent.

Not a member of The Correspondent yet?

The Correspondent is a member-funded, online platform for collaborative, constructive, ad-free journalism. Choose what you want to pay to become a member today!

Not a member of The Correspondent yet?

The Correspondent is a member-funded, online platform for collaborative, constructive, ad-free journalism. Choose what you want to pay to become a member today!

Dig deeper

First rule of fight club: power concedes nothing without a struggle

In an interview that spans continents and centuries, Cambridge University academic Priyamvada Gopal connects the legacies of empire to present day struggles – be they to prevent climate catastrophe, or win self-determination. Class is in session!

First rule of fight club: power concedes nothing without a struggle

In an interview that spans continents and centuries, Cambridge University academic Priyamvada Gopal connects the legacies of empire to present day struggles – be they to prevent climate catastrophe, or win self-determination. Class is in session!