Several winters ago, an Adidas advert appeared on a billboard on my street. It featured a photograph – black-and-white with a hint of colour – of a young woman in running gear gazing proudly into the camera. The caption read: “I am positive energy.” A little further along the street, another larger poster covered the bus stop: a running shoe poised for action – toe down, heel up – emblazoned with the same caption.

I am positive energy.

Read this story in a minute.

In the weeks that followed, I passed both runner and shoe nearly every day as I shuffled along, shoulders stiff and back hunched, pushing my child’s stroller. The slogan struck me as rather strange – after all, energy is something you have, not something you are – but the campaign itself stirred a wistful longing in me. It was January, I was exhausted, and Adidas was promising an energy boost.

Energy is the great panacea of our times. It’s found in energy drinks, power bars, vitamin supplements and superfoods. It can be obtained through yoga, mindfulness, power naps and running. Or, for a quick fix, we can turn to coffee, cigarettes or drugs. Blogs and self-help books teach us how to banish stress, a notorious energy-killer. Management books with titles like Energy Leadership and The Energy Bus promise to boost energy levels in the workplace. As one such book proclaims: “Positive energy is like muscle. The more you use it the stronger it gets. The stronger it gets the more powerful you become.”

The “positive energy” mentioned in the Adidas campaign – and in countless wellness blogs, advice columns and self-help books – isn’t the kind of energy that can be expressed in the amount of calories you consume and burn. (Strictly speaking, running actually costs your body energy.)

No, the kind of energy we’re talking about is altogether more mysterious and subjective: mental energy. Vitality. Joie de vivre. Motivation. Enthusiasm. Zeal. The kind of energy that children are simply bursting with, and that their parents sadly lack. It’s an energy that is both fleeting and capable of being renewed. It’s not something you can measure; it’s something you feel. And, crucially, it’s something you can boost – with new running shoes, for example.

That winter, it occurred to me that Adidas’s attempt to tap into our society’s deep-seated hunger for energy was truly a sign of the times. After all, we’re living in what Byung-Chul Han calls “the burnout society”.

Exhaustion is not a modern phenomenon

The diagnosis is clear: globalisation, an increasingly flexible labour market, and the demands of our performance-driven society put us under constant pressure to reach our “full potential”, while technological developments like the internet and smartphones have given rise to a 24/7 economy, forcing us to be “on” at all times.

Expectations are high, and yet we’re struggling with stress and exhaustion from an increasingly early age. Depression, which counts fatigue as one of its primary symptoms, has reached epidemic proportions, affecting more than 300 million people worldwide.

These issues affect us not just on an individual level but also on a societal one – not to mention the economic consequences. According to the World Health Organization, mental health issues like depression and anxiety disorders cost countries a trillion dollars each year in lost productivity and absenteeism. In other words, we could all work much harder – if only we weren’t so exhausted all the time!

Today, as in the 19th century, we tend to blame our stress, insomnia and burnout on external factors, particularly technology

A few months after the Adidas campaign, literary historian Anna Katharina Schaffner published Exhaustion: A History, in which she argues that exhaustion – and the accompanying desire for more energy – is not a uniquely modern phenomenon.

As Schaffner points out, the ancient Greek physician Galen of Pergamon wrote about the causes of "melancholy", an ailment characterised, among other things, by a lack of energy. During the Middle Ages, theologians railed against the sin of "acedia", which included symptoms like lethargy and a lack of motivation. And in the late 19th century, many western Europeans and US Americans suffered from “neurasthenia”, or nervous exhaustion, which manifested primarily as extreme fatigue. It was said to be the result of a “lack of nerve force” and was triggered by the pressures of capitalism and by technological innovations such as the steam train, the telephone and the telegraph.

While exhaustion has always been with us, the ways we explain and interpret it have differed throughout the ages, says Schaffner. Today, as in the 19th century, we tend to blame our stress, insomnia and burnout on external factors, particularly technology.

‘Charge, baby, charge’

In his book 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep, art historian Jonathan Crary argues that our unrelenting 24/7 economy was made possible in part by technological advances, such as fibre optic cables and smartphones, and that the internet contributes to our mental exhaustion by encouraging information overload.

But though we attribute our lack of energy to factors outside our control (which suggests that it is a collective problem), we’ve come to believe that the solution must come from within, making it the responsibility of the individual. Here, too, technology plays an important role – this time in the form of a metaphor.

From the early 19th century onwards, in the Industrial age, the human body was often compared to a machine or an engine. Now, in the 21st century, rechargeable batteries have replaced machines as our metaphor of choice. In an era when blinking red battery icons on our smartphones, tablets and laptops send us all scrambling for our chargers and when Tesla Motors inspires widespread fascination and admiration, the battery is an apt symbol for our modern, energy-dependent lives.

Countless self-improvement articles and blogs say that energy may be fleeting, but we can get it back if only we do (or buy) the right things

Consider, for example, The Energy Project, a global consulting firm whose clients have included Google and Microsoft. In a 2014 report, published together with the Harvard Business Review, they argued that the 21st century calls for a “new kind of leader”: the chief energy officer. The chief energy officer’s job is to “mobilise, inspire, focus, direct, and regularly refuel the energy of those they lead”. According to The Energy Project, we’re at our best when we “pulse rhythmically between spending and renewing energy”.

Or take Swedish furniture giant Ikea, which, in 2018, ran an ad campaign urging consumers to turn their bedrooms into “a place to recharge”. One commercial showed a young family crawling into bed after a long day. While they slept, battery symbols appeared next to their heads, charging slowly but steadily until reaching 100%, at which point the family members woke up looking bright, cheerful, and ready to face a new day.

That same message was splashed across posters, billboards, buses and trains in my city, Amsterdam. The most surreal version featured a close-up of a sleeping baby accompanied by the text “charge, baby, charge”.

While energy may be enigmatic and fleeting, we can get it back – we can refuel, recharge, boost our energy levels – if we only do (or buy) the right things. At least, that’s the position taken by the countless blogs and self-improvement articles exhorting us to go for regular walks, take up running and meditating, and switch off our phones at the weekend. We need this kind of “mental downtime”, the argument goes, if we’re to recharge.

How the rechargeable battery became a symbol of our age

In a way, it makes sense that the rechargeable battery has proved to be such an attractive metaphor for our times. After all, it echoes that other energy debate – the one concerned with climate change, dwindling fossil fuel reserves and the promise of sustainable, renewable energy sources, such as solar, wind, and tidal power.

Climate activists have long been concerned about the harmful effects of extractivism, a political ideology that can best be summed up as “take, take, take” and that treats the earth as a boundless resource to be exploited with impunity. It is a view that has been condemned by scientists, policymakers and progressive businesses, who agree on the need to transition to renewable energy sources.

Seen in this light, the “positive energy” in the Adidas campaign is a fitting parallel to the green energy that will stave off climate change. Just as renewable energy sources can save civilisation from itself, activities like running, meditation and power naps can help prevent burnout – and safeguard the economy in turn.

No matter what the management gurus try to tell us, the idea that our brains are inexhaustible sources of energy is clearly wishful thinking

It promises to be a harmonious confluence of interests. Together, we will banish exhaustion once and for all. Everyone wins. If we transition to a circular economy and ensure that nothing useful is lost, a perfect world of balance and equilibrium lies within our grasp.

As if time were plentiful and mortality didn’t exist.

And therein lies the problem. Because no matter what the management gurus try to tell us, the idea that our brains are inexhaustible sources of energy is clearly wishful thinking. Our physical bodies will gradually decline and, eventually, give out. The same is true, by the way, of batteries – while they can be recharged many times, even the most powerful battery will eventually call it quits. When that happens, they must be replaced (and hopefully recycled).

I am positive energy

Unfortunately, this isn’t something that tends to come up when we talk about the importance of taking time to recharge.

The fact that we humans prefer to deny our own mortality is nothing new, of course. But our widespread worship of youthfulness may well have made the concept of boundless energy more irresistible than ever before. But as painful as it might be to accept, the truth is that our time here on earth is limited. We won’t last forever, no matter how many pairs of running shoes we buy, how often we meditate, or how hard we try to recharge.

We reveal another crucial difference between sustainable energy and mental energy when we ask ourselves: who benefits? Switching to sustainable, renewable sources of energy is a collective effort that transcends our individual ambitions and serves a greater goal – the preservation of life on earth. Not just for ourselves but for future generations. In contrast, the benefits of recharging and boosting mental energy are primarily felt on an individual level, in the form of improved performance, with economic growth coming in second.

We won’t last forever, no matter how many pairs of running shoes we buy, how often we meditate, or how hard we try to recharge

In that sense, the online video ad that accompanied the Adidas “positive energy” campaign was particularly telling. It featured three fit, fiercely competitive young women running through the city accompanied by upbeat music, spurred on by the sight of one another. Life is a contest.

I am positive energy – emphasis on the “I”.

If our views on mental energy and sustainable energy are so similar, why not take this parallel one step further and ensure that our efforts to live more energetic lives also serve a higher, more collective goal? As individuals, we have a limited shelf life, but the society to which we devote our energy will be around for much longer.

The current narrative, which dictates that individuals are responsible for recharging themselves to resist being drained by our capitalist, technological society, prevents us from finding alternative strategies for dealing with our pervasive sense of exhaustion.

‘No’ is the opposite of negativity

Rather than participating in an increasingly competitive, performance-driven society, we could stop and question the premise on which it’s based. We could collectively say no to some of the demands it places on us and to the idea that everything – even our sleep, our leisure time, and our physical activity – can and should be geared toward achieving maximum performance.

For that, of course, is the great irony of the human-as-battery metaphor: we must take time to recharge in order to avoid burning out so that we can work longer, harder, and more efficiently in service of the very system that is draining us. We crave more energy so that we can produce and consume more of what’s costing us energy in the first place.

Perhaps I don’t want to spend my limited time here on Earth being productive

While it may very well be true that having more energy would make me more productive, perhaps I don’t want to spend my limited time here on Earth being productive.

In this age of “Just do it” and “Yes we can” , refusal has come to be seen as something negative. “No” is what tired, worn-out people say. “No, stop that” is what sleep-deprived parents tell their enviably energetic children. “No, I would prefer not to” is what Herman Melville’s famous character Bartleby says again and again, until starving, exhausted and depressed, he finally breathes his last.

Yet it seems to me that saying “no” to the illusion of rechargeability is the exact opposite of negativity.

Or, as Adidas would put it: it is positive energy.

This piece first appeared on De Correspondent. It was translated from Dutch by Megan Hershey.

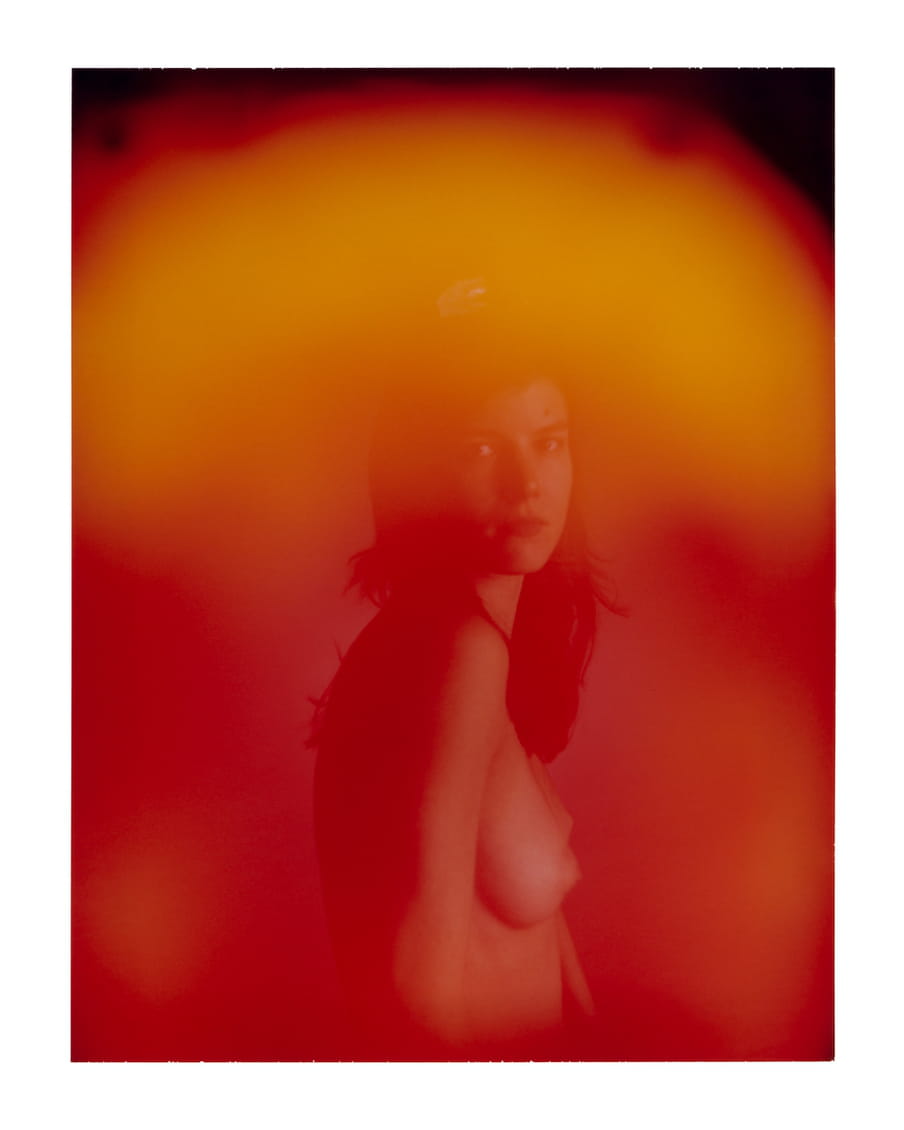

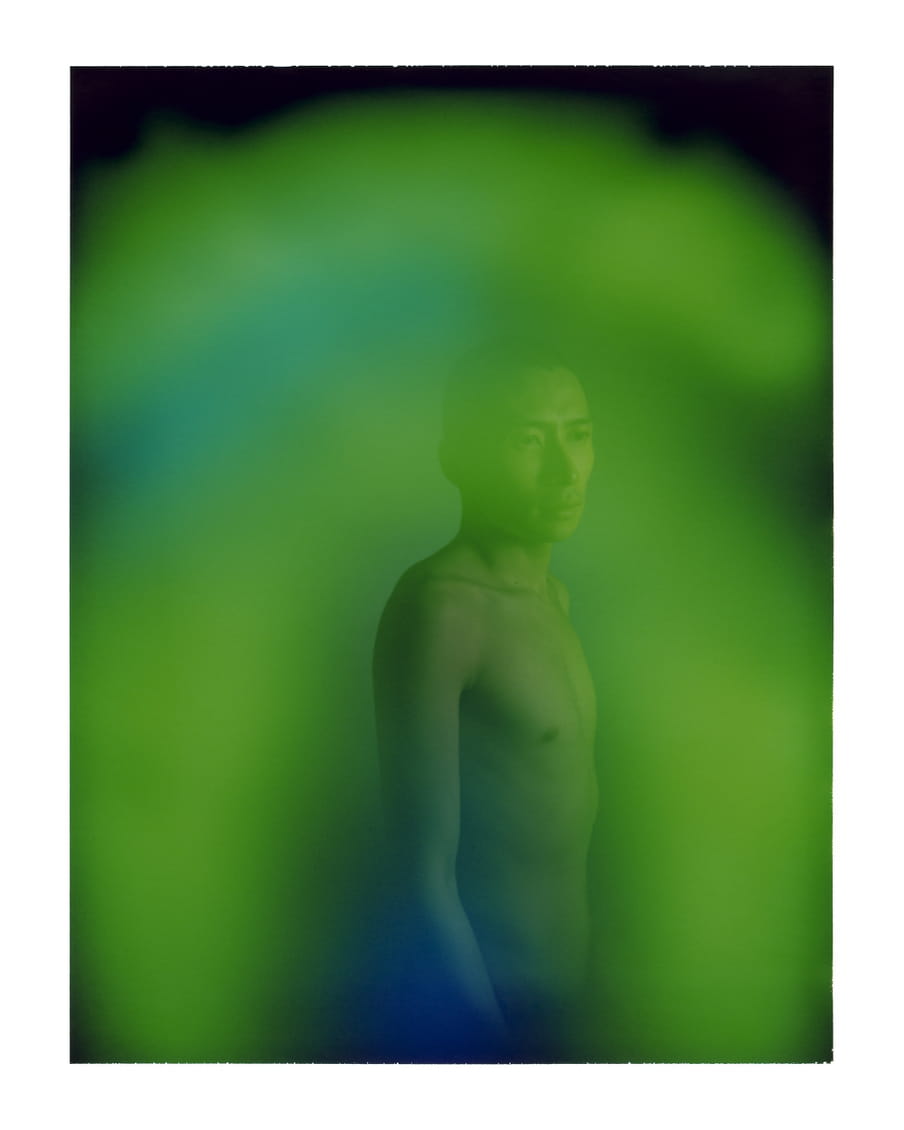

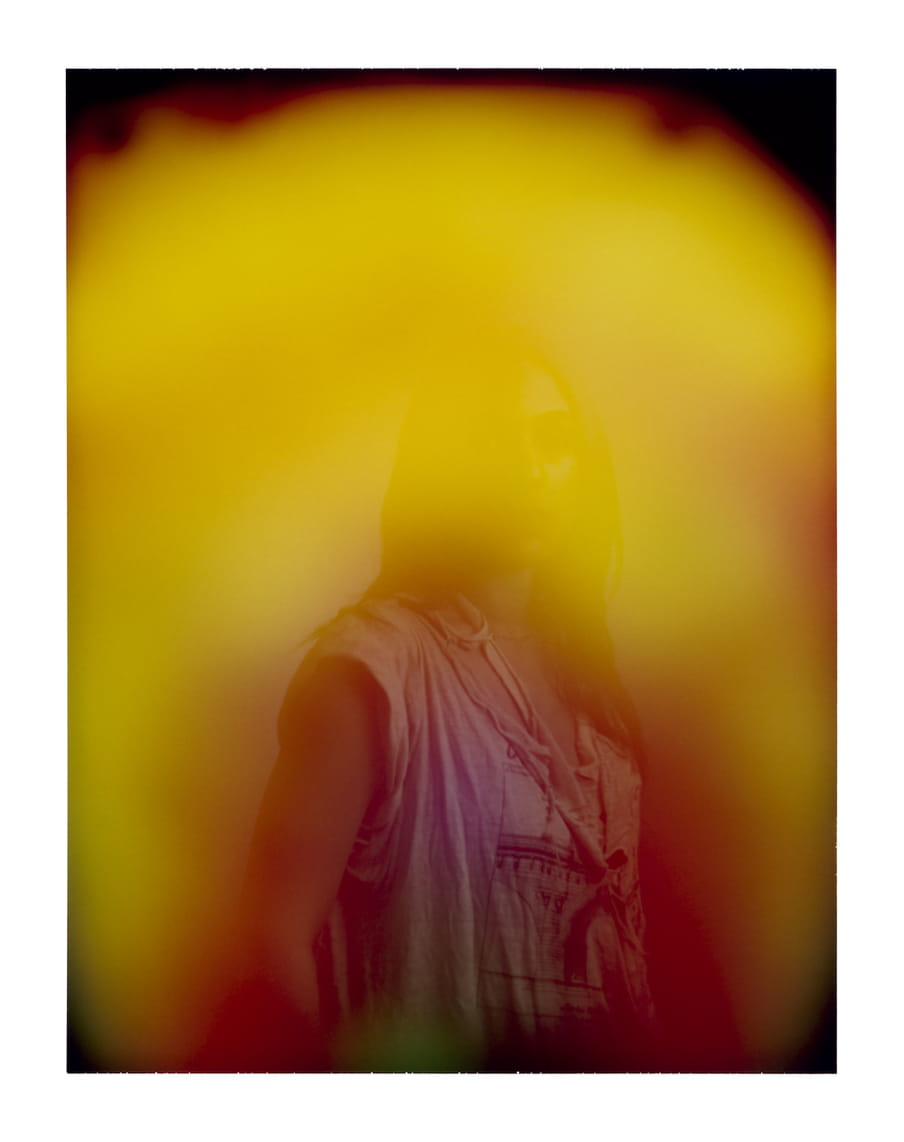

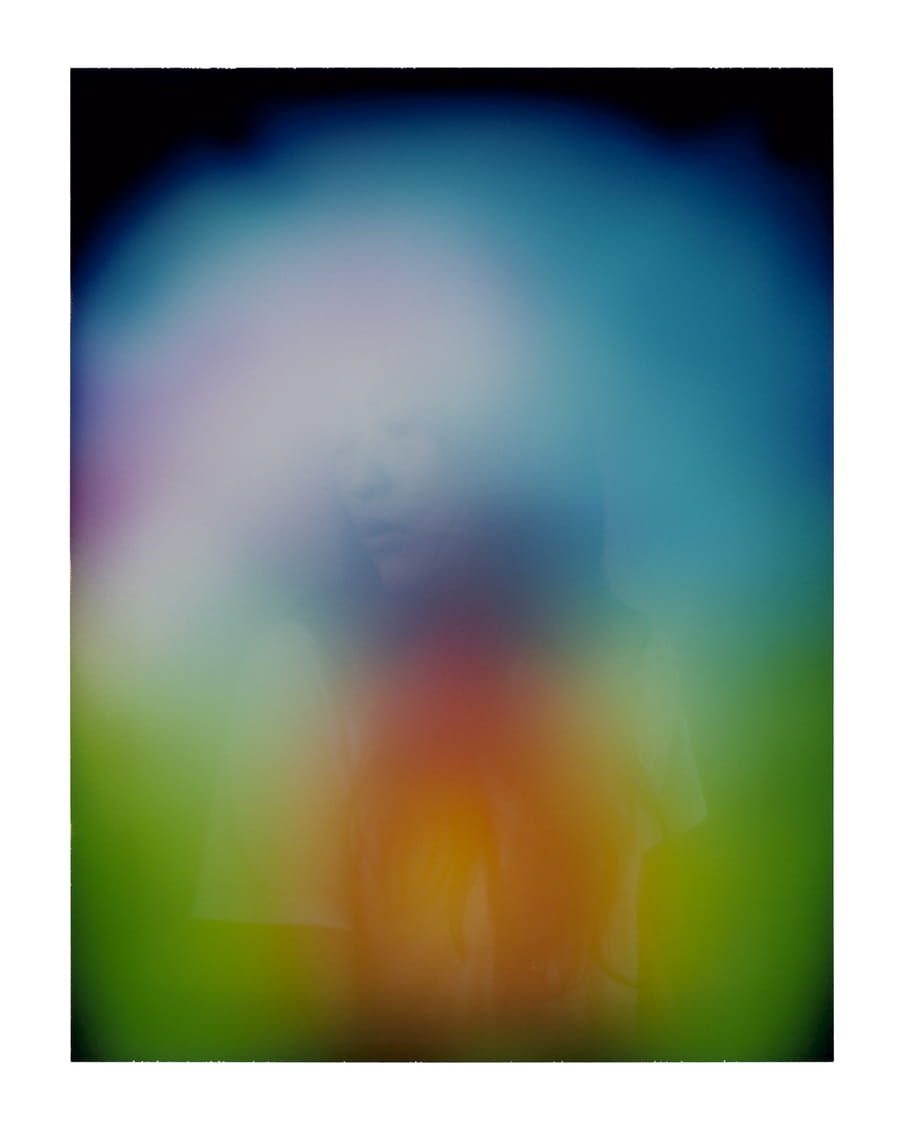

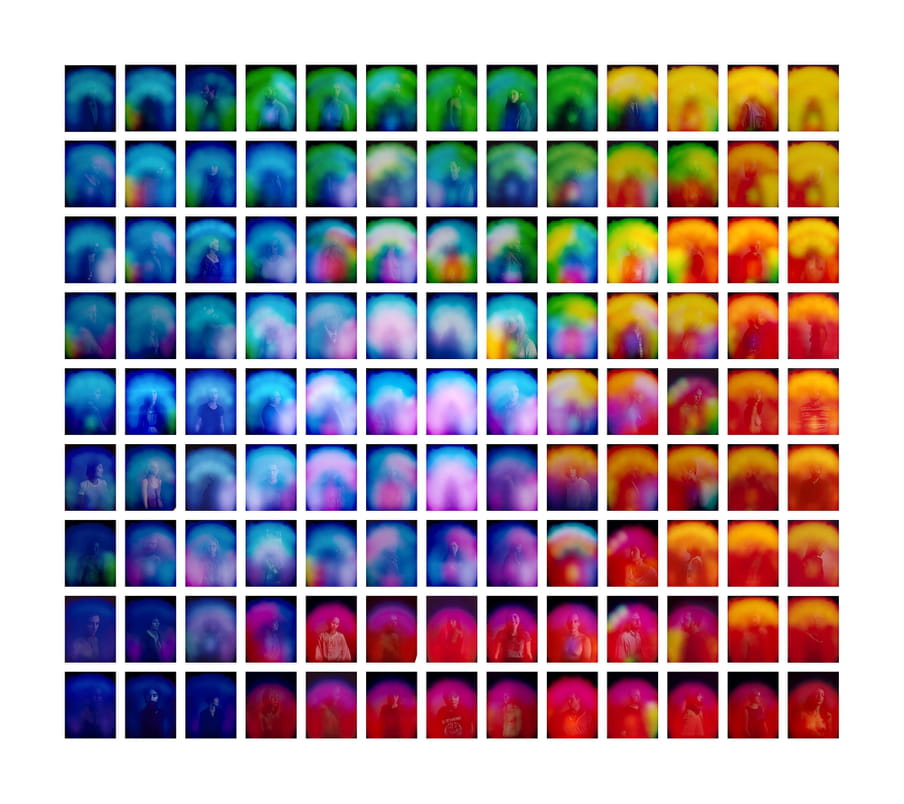

About the images

The strange-looking portraits from The Portrait Machine Project by Carlo Van de Roer are made using a Polaroid aura camera. This machine was developed by a US inventor to document in a photograph what a psychic might see. By connecting the subject to the camera with sensors, the camera measures electromagnetic biofeedback and translates this information about the subject’s character into an image. The idea that a camera might be able to show unseen aspects of the human body may seem ridiculous to some - with good reason probably - but so did the X-ray when it was just invented. (Lise Straatsma, image editor)

About the images

The strange-looking portraits from The Portrait Machine Project by Carlo Van de Roer are made using a Polaroid aura camera. This machine was developed by a US inventor to document in a photograph what a psychic might see. By connecting the subject to the camera with sensors, the camera measures electromagnetic biofeedback and translates this information about the subject’s character into an image. The idea that a camera might be able to show unseen aspects of the human body may seem ridiculous to some - with good reason probably - but so did the X-ray when it was just invented. (Lise Straatsma, image editor)

Not a member of The Correspondent yet?

The Correspondent is a member-funded, online platform for collaborative, constructive, ad-free journalism. Choose what you want to pay to become a member today!

Not a member of The Correspondent yet?

The Correspondent is a member-funded, online platform for collaborative, constructive, ad-free journalism. Choose what you want to pay to become a member today!

Dig deeper

The modern workplace is toxic. We need to overhaul how we think about mental health at work

Stress and excessively long working hours contribute to the deaths of approximately 2.8 million workers every year. We urgently need to rethink mental health in the workplace. Here are four ways to start.

The modern workplace is toxic. We need to overhaul how we think about mental health at work

Stress and excessively long working hours contribute to the deaths of approximately 2.8 million workers every year. We urgently need to rethink mental health in the workplace. Here are four ways to start.