What can a literature researcher teach us about freedom? As it turns out, quite a lot. To be precise: 600 pages of essential reading on riots, demonstrations, rebellions, petitions, strikes and revolutions.

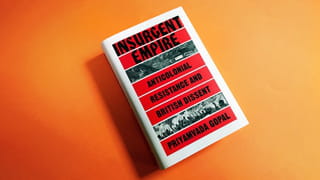

Priyamvada Gopal teaches in the Faculty of English at the University of Cambridge, but this India-born academic is also so much more. A leading left-wing thinker, and public commentator in the United Kingdom, and a force to be reckoned with on Twitter, Gopal has spent years digging through old books and dusty papers in libraries and archives all over the world to produce Insurgent Empire: Anti-colonial Resistance and British Dissent, a book that, page after page, takes apart the idea that Britain “granted” freedom to the people enslaved by its empire. In it, she looks deeply into the historical record for examples of how people living under the most extreme forms of domination imagined freedom for themselves, how they fought for it, and how they won.

Read this story in a minute

Insurgent Empire drips with the blood and sweat of people around the world who fought colonialism. They not only won their freedom but also shaped ideas of emancipation back in the colonising nation, the UK. Gopal makes clear that freedom from the racism, exploitation, brutality, humiliation and environmental devastation of colonial rule didn’t happen only through lofty speeches and fine words. It was won through uprisings in the streets and fighters in the mountains.

Although it covers the past, the book feels urgent. From Brazil to the US, India to Saudi Arabia, authoritarian governments are on the rise all around the world. And regardless of where you live, many of us now share a sense of being trapped by global economic structures and political systems that prevent us from tackling the climate catastrophe.

So I spoke to Gopal because I wanted to know: what can these lessons from the past teach us about how to get free today?

Tell me about your upbringing and early life. How did it shape the work you do and how you see the world?

I grew up in different places in south Asia, but I did high school in Vienna, Austria, between ages 14 and 18, back in the mid-80s. Before that, I was in Sri Lanka and Bhutan, so it was very much not an Indian but a south Asian upbringing. India was part of it. My father was a diplomat, so he was posted in all these different places.

I guess moving to Vienna was quite formative in terms of encountering Europe and a particularly European brand of what, at the time, was very virulent racism. In that sense, it was formative for my thinking about race and empire and that kind of thing, but it wasn’t something I was consciously doing.

What do you say to those who consider colonialism as just another historical episode that is over and done with?

That is manifestly incorrect, isn’t it? Immigration, race relations, global hotspots like Palestine, Kashmir and Iraq, and concepts such as free trade and foreign aid all emerged out of the crucible of empire. And they continue to shape so many lives both within and outside Britain.

‘There is hope in resistance’ - Priyamvada Gopal

As long as we live with capitalism as a global economic system, we haven’t left the age of empire behind us. Colonialism’s first and most important driving force was the search for profit, resources, and markets. That dynamic remains with us.

From your research, what do you think freedom meant to those living under colonial occupation?

Freedom was always contextual – never an absolute. That is the most striking discovery, really, that people defined freedom based on fairly specific local requirements.

For the rebels of Morant Bay, Jamaica, in 1865, it was about the right to self-sustain on small plots of farmed land. For the Pan-African movements of the early 20th century, it meant freedom to aspire to education and development without being cast as irredeemably backward because of racist science, but it also meant, crucially, freedom from tyranny, subordination, poverty, and capitalist exploitation. For the Kenyan rebels of the 1940s and 50s, it was about recovering land as communal property and a source of collective wellbeing.

The point really is that most anti-colonial struggles expanded the range of what freedom means.

Insurgent Empire is a book that goes back hundreds of years, but reading it, I was struck by just how timely it feels. Why did you need to write this book now?

The book spans about a century from 1857 to the 1950s, so the last of the episodes was well under a century ago. Some of the feel of the narrative comes from the fact that the age of empire was not, in fact, all that long ago, despite public perception that it sits in the hoary past. Given that the end of formal colonisation for the most part wasn’t until the 1980s, we do actually live with the empire much closer to our present than we often assume.

The book also feels urgent.

Anti-colonial struggles raised many issues and won partial, sometimes temporary, victories. They were rarely only about sovereignty and national independence. The struggles in the book remain very much alive in the present: labour, migrant rights, defending the right to protest, anti-racism, anti-fascism, and the rejection of militarism and of authoritarian government. So it doesn’t surprise me that the narrative feels very contemporary, something many audiences, in more than one country, have remarked on. We are after all witnessing a global resurgence of authoritarianism.

Learning how to make alliances without gliding over differences is a task we face today.

In the book you show the deep capacity people have to learn and think differently, even when they benefit from an oppressive system like colonialism. But you have yourself faced plenty of hostility during your decades of teaching in Britain. Aren’t you being quite generous towards Britain?

I’ve never thought Britain’s radical traditions are anything but remarkable and inspiring, despite some of their occasional myopia around race, gender or sexuality. It also became clear to me while researching this book that while Britain’s liberal traditions are a mixed bag, some liberals were radicalised by witnessing or learning from anti-colonial struggle and became important allies. Learning how to make these alliances without necessarily gliding over differences was a task they had to undertake and that faces us as well today.

There’s been hostility, of course, and still is, but it would be wrong to minimise the solidarity and alliances I myself have made over the years I’ve lived in Britain.

Some people talk about a sort of a "balance sheet" for colonialism, which weighs the "positives" (education, commerce, law and order, and, inevitably, railways) against the "negatives" (atrocities, rights violations, genocides, land expropriation). What do you think about this and the appeal it seems to carry?

What could be ultimately more crudely moralistic than a “balance sheet”? As though you can pit three massacres and two famines against, let’s say, three railroad tracks, one bridge and a port. How on earth does one assess the good done by the latter against the "regrettable" evil done by the former?

The point is precisely that you can’t weigh these things up against each other. The balance sheet approach does remind us, however, that for many centuries, those in power did think of other human beings, especially non-European human beings and the poor, as mainly figures in a ledger, even merchandise in some cases. Those habits of thought have lodged deep in our societies, and they are ones that we need to view very critically indeed.

I also frequently come across people saying it’s “anachronistic” to judge colonial history by the moral standards of today. What do you think about that?

There’s this facile idea that “back in the day” people didn’t really have problems with, say, slavery or dispossession or massacres. That is simply untrue. It is an enormous retrospective condescension on our part. People both in and outside Britain challenged what they saw at the very moment as ethically dubious and politically suspect.

I very much want young Britons who are repeatedly urged to be proud of the imperial past to have access to a different past. A past in which their ancestors stood up and challenged the empire. That history has been marginalised and obscured, possibly quite deliberately so.

Anyone who was in the US in September 2001 – as I was – cannot be surprised by the rise of authoritarianism. A lot of what we’re seeing now has come to fruition from that period onwards.

You have described the present government of India in terms of colonial rule. What do you mean by this?

Colonialism’s damage was not restricted to the famines or the dispossession. It worked happily with native tyrants and indigenous structures of oppression in order to consolidate itself. When it left, it not only continued to work profitably with post-colonial elites but also left behind strong colonial states with repressive legislation put in place precisely to deal with dissent.

So you have a situation where colonial-era laws like the one against sedition [criticism of the state] are used freely and militaries that were left behind – the Indian army is a direct creation of the Raj – continue to act with impunity.

The situation in Kashmir is a typical example: a mess left behind by hasty and thoughtless British withdrawal. Both India and Pakistan are fighting over the region. How ironic is it that an independent nation that was the outcome of a struggle for self-determination has absolutely no interest in the claims to self-determination of the Kashmiri people?

To me, to not abide by the emancipatory principles of the anti-colonial struggles which brought you sovereignty, to not do unto others as you demanded be done unto yourself, is the ultimate betrayal.

Has the recent turn towards authoritarianism surprised you?

Are you talking about India or America or Britain, or all of them?

All of them.

It’s not been surprising for anyone that has watched the last couple of decades unfold. But I think the speed of the spiralling into very deep forms of chauvinism, xenophobia, authoritarianism (particularly in India and to some extent in the US) has been very worrying.

You can’t say "surprising" as many things have led up to it. Anyone who was in the US in September 2001 – as I was – cannot be surprised because a lot of what we’re seeing now has come to fruition from that period onwards.

In India, I might say I’ve been taken aback by the speed with which the last five years has really undermined Indian democracy. It was never a perfect creature to begin with, but the speed with which there is now explicit use of authoritarian legislation is certainly staggering. I never want to talk about surprise, because I think you have to have not been paying attention to be surprised. But you can still be taken aback.

With all that’s happening, it’s easy to feel hopeless or feel a sense of panic. What gives you hope?

Seeing people protest in the face of what really does seem absolute. That gives me hope. Being in India now and having seen five years of silence, or very minimal dissent, it’s very energising to see that even in the face of the juggernaut of state violence, people are digging their heels in and saying “no!”.

Equally, I also understand now that peaceful resistance is going to be very difficult. Because what is being marshalled against dissidents – that’s true in the US and also Britain – is immensely violent. You see that already in terms of how certain sections of Extinction Rebellion have been treated – criminalised, seen as extremists and so on. This is all preparatory to violence, to justify state violence.

Someone like Steve Bannon has spoken in terms of civil war. And so, yes, there is hope in resistance, but the question is what will this resistance face in the months and years to come. So any hope I have is very cautious.

You’ve become known for your Twitter account. When you’re on social media are you concerned with changing people’s minds?

I don’t think that hardcore people on any site are about to change their minds. I do think, though, that there are a large number of people who are on Twitter – believe it or not – to learn.

There are things I’ve learned about contexts I don’t know much about from people who do know about those contexts. For example, I’ve learned a lot about issues to do with trans life and trans identity and trans politics from people and debates I’ve seen unfold on Twitter. But that’s a very different thing from saying: “I’m going to change the mind of someone who embraces a radically different position.” I don’t think that can happen.

If all oppression is connected, what are the struggles around the world today that you see carrying forward the best of earlier fights for freedom? And what might those committed to fighting climate catastrophe learn from anti-colonial movements?

There are several. Perhaps the most inspiring leadership comes from different Indigenous and tribal groups throwing their energies and lives behind defending land, forest, and environment in areas as far apart as the Amazon, Canada, India and Australia. Movimento Sem Terra has been fighting these battles for years in places like Brazil.

Power concedes nothing without a struggle, and struggles require solidarity and alliances across racial and national lines.

These are, of course, groups and people who are still experiencing the force of fairly direct dispossession and colonialism. Similarly, movements for Palestine and Kashmir carry forward strong anti-colonial traditions. Civil disobedience movements in India where many campaigners are calling for a boycott of the National Population Register are also self-consciously drawing on tried and tested techniques from older anti-colonial struggles.

The point is to start where you are, but build alliances and links internationally. That was the ultimate lesson of anti-colonial struggle.

A final question: what do you want people to take from your writing?

I very much hope people will take away that there is a backstory to both oppression and struggle, and that, as Frederick Douglass reminds us, power concedes nothing without a struggle. So I hope people will be reminded that whatever rights we enjoy today, however besieged, those were won out of struggle. Equally, those struggles necessitated and elicited solidarity and alliances across racial and national lines. This, in our so deeply interconnected world, is not just an option. It’s a necessity.

This interview has been edited and shortened.

Dig deeper

The past is still present: why colonialism deserves better coverage

Talking about everyday things may seem banal, but great injustices happen when people grow accustomed to them. As the Everyday Colonialism correspondent, I intend to lead better nuanced, more accessible conversations.

The past is still present: why colonialism deserves better coverage

Talking about everyday things may seem banal, but great injustices happen when people grow accustomed to them. As the Everyday Colonialism correspondent, I intend to lead better nuanced, more accessible conversations.

The case against civility: who is your niceness really helping?

Let’s imagine that you have your foot on my neck. To say you’ll consider removing it but first I must ask nicely, is to ignore my discomfort – and to maintain your power over me.

The case against civility: who is your niceness really helping?

Let’s imagine that you have your foot on my neck. To say you’ll consider removing it but first I must ask nicely, is to ignore my discomfort – and to maintain your power over me.