Three countries, three stories of survival. Our postcards from the fire frontlines show how communities have responded to climate disasters.

In Valparaíso, Chile, wildfires besieged the colourful houses on the hills of the city in 2014 – and they struck again on Christmas Eve last year. Having lived there for generations, the local community refuses to leave the hills. And in any case, where would they go? Jacinta Molina reports from the ground.

In Gran Canaria, Spain, whirring helicopters fighting fires were the soundtrack to Matthew Hirtes’s summer. But politicians are stuck in a tug-of-war blame game while parts of their country burn.

In Australia, the world has watched as the country experiences bushfires on a scale so huge that it’s hard to comprehend. But there are solutions. First Nations writer Neil Morris urges the empowerment of the first custodians of the land.

In Valparaíso, Chile, poor communities cling on after all is lost – a second time

The port city Valparaíso is famous for the colourful houses and elevators perched on its hills. But since a blaze spread over 40 hectares of land in December 2019, much smaller but reminiscent of the one in 2014 – the largest in the Chilean city’s history – Valparaíso is also increasingly known for its wildfires.

Celia Díaz’s home in the ravine of San Roque hill was quickly destroyed by a fast-moving fire which swallowed over 250 houses on the warm and windy days of 24 and 25 December. Díaz had lost everything once before in the fire of 2014.

The cause of these fires remains unclear, but there seems little doubt that a changing climate has led to hotter and drier weather – ideal conditions to accelerate a blaze. “It’s not clear yet what is the specific role of climate change as cause of the fires,” says Ariel Muñoz, a professor at the Institute of Geography at the Pontifical Catholic University of Valparaíso. “However, it is [important] to consider the climate change effect in the spread of the fires due to the [worsening] of environmental conditions which trigger the spread.”

Recommendations to leave San Roque hill have often been met with resistance from the local community, who see it as a solution from bureaucrats with little attachment to the city.

The people most affected, those whose homes were perched on the most hard-to-reach parts of the hills, were, to a large extent, Valparaíso’s poor. Despite their colourful exterior, the houses built over those ravines hide a precarious way of living: several families crowded into small homes with the most basic facilities. Díaz shared her small plot with two more families. Hers, like many other houses here, is made from a lightweight, easily flammable material. Garbage disposal services have real difficulty accessing many of the communities on these hills, and so residents resort to dumping their waste into the ravines. The buildup of trash helped spread the flames.

Learning whatever lessons they can from the wildfires, there are resident schemes to recycle some of the waste locally and clean up the ravines. Muñoz also recommends changing farming practices, encouraging the cultivation of less flammable vegetation instead of the eucalyptus and Monterey pine trees presently grown in this part of Chile. The municipality says it is working on maintenance plans as well as energy efficiency measures, such as the use of renewable energy. But it needs help from the government – especially to educate the community about fire risks – to better manage recycling and to improve infrastructure.

Recommendations to leave San Roque hill, and other spots like it, have often been met with resistance from the local community, who see it as a solution from bureaucrats with little attachment to the city. Undoubtedly, many refuse to leave simply because they have nowhere else to go, but for others it’s because they have lived on these colourful slopes for generations. Residents are reluctant to leave for what could be an uncertain future.

“I like living in the hills,” says Díaz. “The only way I would leave this place is if someone gives me a farm. Only someone who has lived in the hills knows what it feels to live in Valparaíso.”

In Gran Canaria, political divisions over climate change continue to smoulder

August 2019 and we were feeling the heat. The spring had been dry and so by 10 August, in central Artenara, a veritable Bedrock where locals live in caves for the warmth in winter and the cool in summer, sparks continued to fly, even after a resident switched off his soldering equipment. The second fire started on Tuesday 13 August in Cazadores, Telde, an ageing farming community, and Saturday 17 August brought the third – and thankfully – final blaze, in north-central Valleseco.

The soundtrack of my summer was the whirring blades of helicopters and aeroplanes above my home. The aircraft, deployed to help fight the wildfires, would replenish their stocks of water from the ocean, before heading back to the heart of the island to continue to douse what had started to feel like an eternal flame. Paying a visit to my wife’s family finca in agricultural Aldea in the west brought us closer to the intensity of the fires. Looking towards the centre of Gran Canaria’s iconic Roque Nublo, the sky appeared to be raining ash.

The annual average temperature on Gran Canaria is 22C. When it dips below 20C, locals don scarves, gloves, and coats. Anything above 25C, and they’re scrabbling for the shade. That August, temperatures shot past 40C, with winds exceeding 70km an hour.

The soundtrack of my summer was the whirring blades of helicopters and aeroplanes above my home.

By 14 August, the fires were thankfully contained, though it took another 11 days to extinguish them completely. First, there was relief and joy as the pilots received a hero’s welcome from residents, who lined the Maritime Avenue to wave banners and flags in appreciation. The chief of emergencies, Federico Grillo, was recognised by the military for his service that summer.

But relief turned to ire when the damage to 25,000 acres of island was discussed in Madrid, in the upper echelons of Spanish government. An official declaration of support for those who had lost land and livestock was blocked by a senator of the far-right Vox party, José Alcaraz, to the bewilderment of even his allies. Alcaraz objected to the declaration because of the reference made to climate change. These are politicians who believe that global warming is a fiction of the left, intended to topple big business. The left, however, did not come away unsinged. Socialist prime minister Pedro Sánchez was chided for not returning quickly enough from his holiday.

With the far right gaining votes in Spain and elsewhere across Europe, there is cause for concern over climate policy. But it is undeniable that in the immediate aftermath of the 2019 fires, it wasn’t the sparks flying in Madrid that caught our attention, but the stars we could once again see over the Canary Islands’ skies.

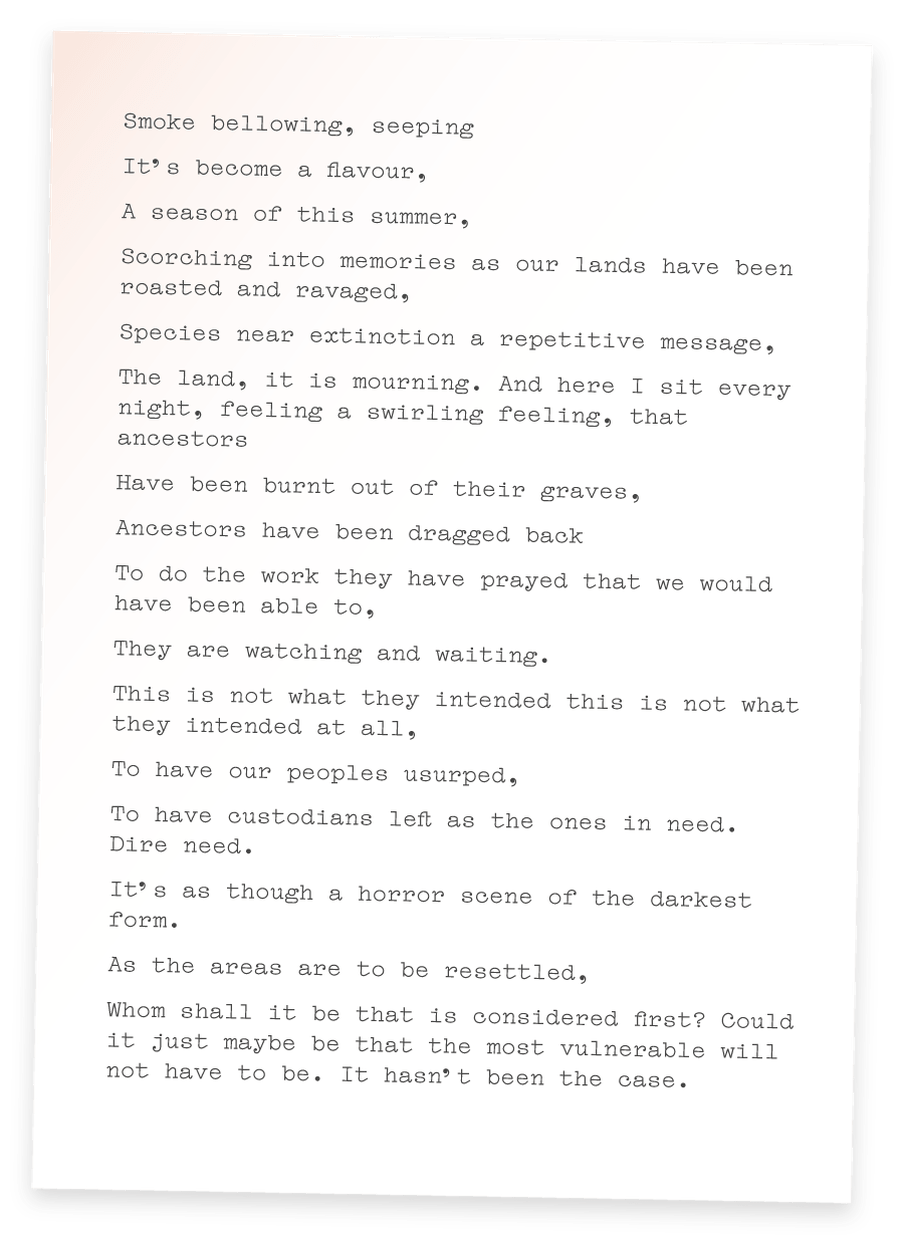

Indigenous Australians hold solutions, but will the nation listen?

As the world watches, Australians have started to look for solutions. We need to find solutions that are the least destructive; solutions that consider human welfare and care as a highest of priorities. These can come from a source that remains marginalised by mainstream society: Australia’s Indigenous communities.

Indigenous peoples have long been speaking about the importance of taking care of the land in a way that is reverent; that recognises the symbiosis between earth and humans; that is holistic. Indigenous land management practices, even when used in small plots of land, have shown great results in Australia’s fire seasons.

There is a clear lack of trust. The view is that if you empower First Nations people or leaders, you may lose all you have: your power, your wealth. But what we have learned from these fires is that ignoring Indigenous leadership leads to losing lives, and losing a way of life that you considered a dream. A dream that was yours only at the expense of others.

The colonial destruction of lives cannot be separated from the destruction of land. Genocide is ecocide, and ecocide is genocide. But Australia can begin to find and make visible solutions that come from the first custodians of the land and apply them at scale.

Dig deeper

Cubatão, London and Delhi: Greetings from the air pollution frontline

Air pollution affects 91% of the world’s population. These three postcards give us three distinct perspectives on a complex, important challenge.

Cubatão, London and Delhi: Greetings from the air pollution frontline

Air pollution affects 91% of the world’s population. These three postcards give us three distinct perspectives on a complex, important challenge.

In 2030, we ended the climate emergency. Here’s how

If words make worlds, then we urgently need to tell a new story about the climate crisis. Here is one vision of what it could look and feel like to radically, collectively take action.

In 2030, we ended the climate emergency. Here’s how

If words make worlds, then we urgently need to tell a new story about the climate crisis. Here is one vision of what it could look and feel like to radically, collectively take action.