A senior human resources executive at one of my former workplaces once called me with an unusual proposal: "The company is planning to start a work group to promote employee wellness, and mental health will be one of our focus areas. I’d like to invite you to be a part of it."

I say "unusual" because the media in India (and in large swathes of the world) isn’t known to care much about mental health. Far too many media outlets flout every norm of ethical reporting on the subject. Not to mention newsrooms themselves have a bleak reputation as workplaces, teeming with people sacrificing their health and wellbeing in a mindless competition for "breaking news".

So my first reaction to the invitation was scepticism. "I know talking about mental health is fashionable right now, and every company wants to jump in," I said, hoping not to sound too cynical. "But you do realise that something like this needs long-term commitment?"

Yes, and that’s why the CEO’s office would be directly involved in the project, I was told.

The group’s first meeting was scheduled for a few days later. But that meeting never happened. The project was shelved even before it took off. I followed up but got no explanation beyond something about "other priorities". A few months later, I left the company.

Before writing this piece, I once again reached out to the executive to ask what had gone wrong. This time, he told me that the project had been put on hold "due to business conditions/financial constraints".

"But it’s on our priority list for sure," he added cheerily. "We will make it happen."

‘Corporate wellness’ is booming, but mental health in the workplace is in tatters

The shift from the industrial economy, driven by physical labour in often brutal conditions, to the digital economy, fuelled by mental labour in sanitised offices, means work has never felt safer. But this facade of safety barely hides what the modern workplace has become: a toxic cesspit of relentless, deadly stress, where a majority of the world’s population spends a third of their adult life.

The call to find a better way of working isn’t new. The internet is brimming with prescriptions for building a "happy" workplace. But more often than not, employers spend a disproportionate amount of time and resources chasing empty frills: wellness committees and work groups, "bring your pet to work" days, and my favourite: bikes you can pedal to make smoothies.

In the US alone, corporate wellness has grown into an $8bn juggernaut. But what has come out of this boom?

In 2019, the International Labour Organisation declared that "stress, excessively long working hours and disease, contribute to the deaths of nearly 2.8 million workers every year" – road accidents kill fewer than half that number – "while an additional 374 million people get injured or fall ill because of their jobs".

The message is clear: we desperately need a new workplace mental health guidebook. Spare us the gimmicks; it is time to demand workplaces that don’t make employees sick to begin with.

Here are four ways to start rethinking mental health in the workplace.

Stop seeing mental health as a ‘productivity’ issue

Workplace wellness drives have their origin in decades-old employee assistance programmes (EAPs). EAPs were a response to, among other things, alcoholism among employees, and, according to one definition, their purpose is to address employees’ "productivity" and personal issues that may affect their "job performance".

Those two terms – "productivity" and "job performance" – are giveaways: most employers seem to only care about their employees when doing so directly or indirectly translates into more dollars. When mental health problems are costing the global economy $1tn in lost productivity, not caring is bad for the bottom line.

Extractive capitalism has trained us to believe that this is perfectly sound logic. After all, companies "do well by doing good" all the time. Except touting business outcomes for doing the right thing is the enemy of wide and sustained change. It might make sense when the goal is to improve something narrow and specific relatively quickly – say, addiction levels in your employees. But if you want to commit to a vast, nebulous goal, such as addressing your employees’ mental health, you have to stop deluding yourself with meaningless perks and start throwing your weight behind real, sweeping cultural changes.

This kind of rewiring will take time and is bound to be frustrating if your only motivation is raising quarter-on-quarter output.

Repeat after me: mental health is a human concern, not a productivity issue.

Stop talking about mental illness as a ‘burden’

From medical journals to government reports, the word most commonly used to describe the toll of all illness is "burden". That trillion-dollar figure the World Health Organization uses to drive home the economic impact of mental illness? That’s technically its "burden" on the global economy.

Given that people who live with mental illnesses already battle deep stigma, "burden" is a particularly odious choice. It marginalises the ill and implies they are a deadweight on society. It causes resentment among those who feel they must shoulder this burden.

Now, recall what the well-intentioned HR executive told me about "other priorities" derailing our mental health work group. That’s the kind of rationale companies typically trot out to cut costs that are seen as unproductive – as burdens – especially when the business runs into headwinds.

The irony, of course, is that it is precisely during a downturn that employees feel the greatest need for psychological assistance. Miriam K Forbes, a researcher at Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia, found last year that "people who suffered a financial, housing-related, or job-related hardship as a result of the Great Recession (2007-09) were more likely to show increases in symptoms of depression, anxiety, and problematic drug use. The declines in mental health were still evident several years after the official end of the recession."

Take the current situation in India. The country is going through its most serious economic slump in a long time. The population – with the highest number of under-25s in the world – is struggling with soaring joblessness. So pervasive is the fear of losing jobs that, according to one estimate, stress-related complaints among Indian professionals doubled in 2019 over the previous year.

Now is the time employers need to prioritise mental health support, not put it in cold storage.

Employers need to end their obsession with winning ‘the war for talent’

In 1997, a team from the consulting firm McKinsey announced that businesses were engaged in "the war for talent", which would determine their survival.

Few other ideas in HR have had the seductive appeal of the war for talent. Its most visible fallout is the race to transform offices from uptight places of business to hip spaces where millennial employees love to hang out, as their employers find ways to serve them more beetroot and fewer fizzy, sugary drinks using cutting-edge data analytics.

The nuance that gets glossed over is that the McKinsey report defined talent as "smart, energetic, ambitious individuals", an exclusive club restricted to the top 200 executives in any company.

"Talent", by McKinsey’s 1997 definition, isn’t everyone in a company. The "war" isn’t being fought to gratify everyone, either. Roger Martin, former dean of Rotman School of Management at the University of Toronto, explains the consequence of this incisively: "Capital (a shorthand for business owners and investors) is outraged because it is being beaten up by talent – whether CEOs, investment bankers, consultants, movie stars, players – and it takes out its anger on the easiest target: labour."

In other words, business owners have to give so much to talent that they are loathe to make any concessions for those who are denied this tag - those who are merely labour. The result is unconscionable income inequality. Martin writes: "The gulf grows between talent – the high-earning, differentiated workers – and labour, those widget makers who support them."

The other thing about wars is that they end. As long as the demand for talent outstrips supply, employers will play nice. But when jobs are scarce and the power balance shifts, as is happening in some places now, those healthy snacks are the first thing to go.

Treat mental health as an inalienable human right

The list of problems is long. Finding solutions needs to start with one declaration: mental health is an inalienable human right. Without it, there is no freedom or dignity.

As the American Psychological Association explains, adopting a rights-based approach to mental health is critical for "clinical and economic reasons, as well as moral and legal obligations".

For instance, in 2017, India passed a new law that brought parity between mental and physical healthcare. The US has the concept of "reasonable accommodation" under the Americans with Disabilities Act, making it illegal for employers to discriminate against employees with certain mental illnesses (though according to a 2014 article, about 90% of plaintiffs who sued under the act lost, and there is constant criticism that the law has created a compensation extortion racket).

Ultimately, legal safeguards, while essential, are not watertight. Making workplaces mental health-friendly will require a cultural revolution, reimagining how and why business is done.

Humanity and profitability can coexist

The good news? None of this means sacrificing profits.

Jason Fried and David Heinemeier Hansson prove this point well. Fried and Hansson are co-founders of Basecamp, a company that makes project management software. Their latest book, It Doesn’t Have to Be Crazy at Work, is a call to embrace slow growth and calm workplaces. Basecamp sets no targets for its teams, doesn’t measure market share, and doesn’t work more than 40-hour weeks. In fact, in summers, its employees work 32 hours.

"Our company fails the real world test in all kinds of ways," the co-founders say – and yet Basecamp is consistently profitable.

Much of what Fried and Hansson argue for can be distilled into one sentence: you can build a healthy workplace – if only you are willing to check your ambition to win at any cost.

"Business is not war. Don’t "target" customers. Don’t "fight" for talent. Don’t "capture" a market. Don’t hire "head-hunters". Don’t pick your "battles". Don’t make a "killing". Eschew the language of war. Put your mind in a positive place," Fried recently tweeted.

So, there’s a start. Ditch the idea of winning wars, forget about selling "happiness", and embrace humanity.

Reward managers who foster open conversations about mental health in their teams, not just those who extract the greatest productivity.

Reward everyone for acts of compassion, not just dedication to duty.

Guarantee pay parity.

Don’t force your employees to lie when they need to stay away from work.

Then give us all the smoothies in the world.

Correction: this piece previously misstated the value of Basecamp as $100bn. The company does not believe in monetary valuation.

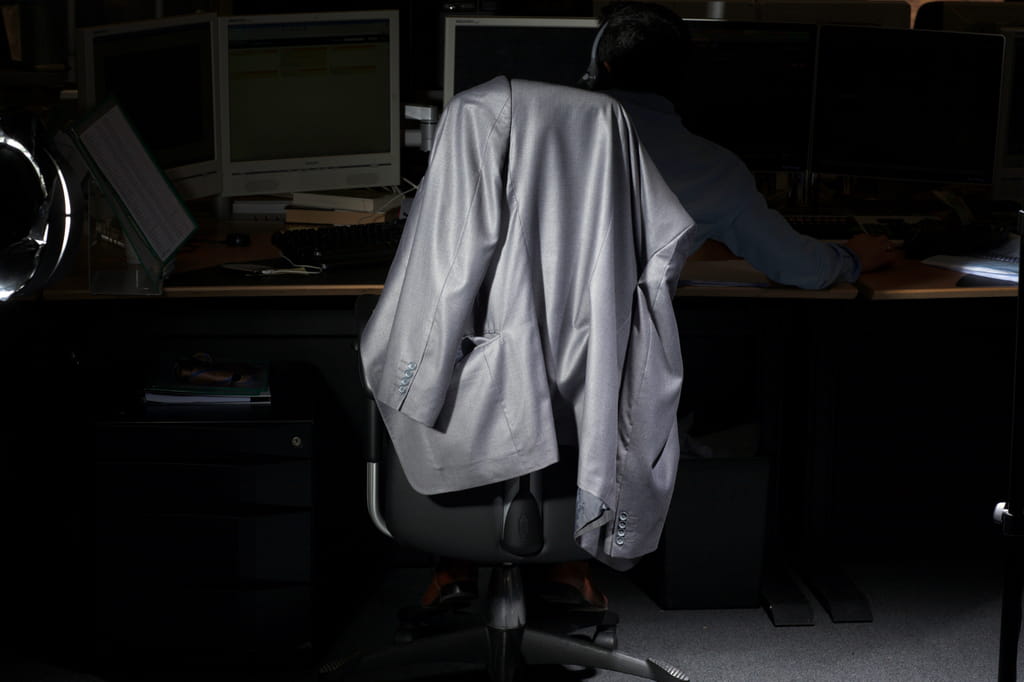

About the images

For 15 months, Florian van Roekel explored different offices throughout the Netherlands to create the series How Terry Likes His Coffee. His candid photographs show the distinctive symbols and aesthetics of office culture. The overwhelming feeling of anonymity and disconnect is enhanced by the flash. (Lise Straatsma, image editor)

About the images

For 15 months, Florian van Roekel explored different offices throughout the Netherlands to create the series How Terry Likes His Coffee. His candid photographs show the distinctive symbols and aesthetics of office culture. The overwhelming feeling of anonymity and disconnect is enhanced by the flash. (Lise Straatsma, image editor)

Dig deeper

‘How’s your mind?’ The quest for new ways to talk about mental illness

My longterm battle with depression and anxiety has made plain the need to reset the way mental illness is perceived, discussed and treated.

‘How’s your mind?’ The quest for new ways to talk about mental illness

My longterm battle with depression and anxiety has made plain the need to reset the way mental illness is perceived, discussed and treated.