Hi,

This is my last newsletter of the year. Writing weekly newsletters has been surprisingly fun. I didn’t think I’d always be able to find something to say, but it would seem that I underestimated myself. Still, in the next several days, I will be taking some time off to be with my loved ones, so you won’t hear from me until we’re firmly ensconced in 2020 (which I think is the most numerically satisfying year we’ve had in a long time. I look forward to writing "2020" all year long!).

This week I’m in Accra, the humid, bustling capital of Ghana. I came here to speak at an event called Adventures Live!, to which I was invited by Nana Darkoa Sekyiamah, a brilliant feminist and communications strategist. Adventures Live! was organised to commemorate the 10th anniversary of the blog Adventures from the Bedrooms of African Women, which publishes exactly what you imagine. The blog was co-founded by Nana Darkoa and Malaka Grant, and for the past decade it has been a valuable community-building and knowledge-sharing resource for women from all over the continent on the subjects of pleasure, sexual freedom, and more.

Nana Darkoa is a dear friend and a great event organiser, so I was excited about this event from the moment I heard about it. I generally find gatherings that prioritise the knowledge, experiences and wellbeing of people who are marginalised really inspiring, and Adventures Live! was no exception. Throughout the day, we talked about pleasure, safety, sex, love, power and freedom from the perspective of queer folks, women, sex workers, and any combination of the three.

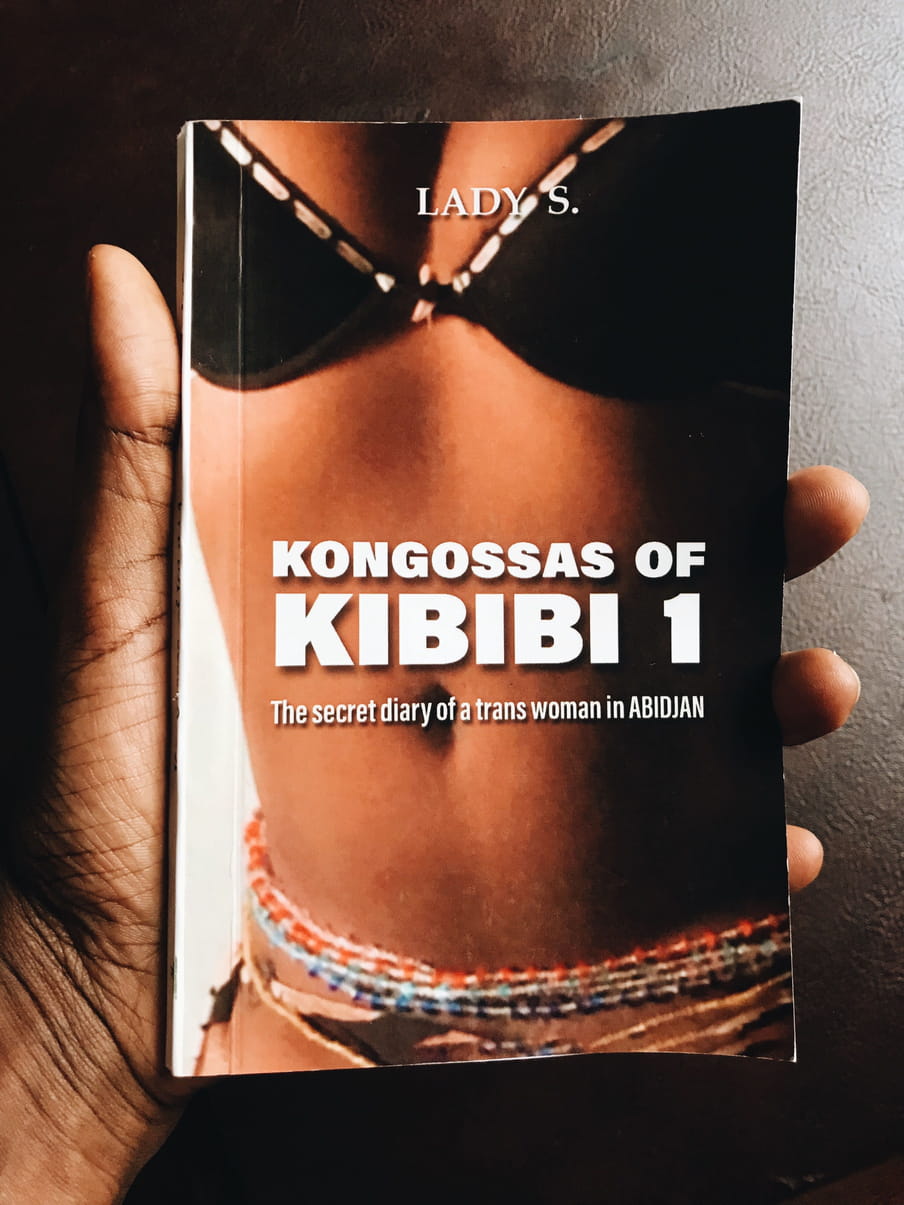

I made new friends, hugged old friends, and held hands with people I had just met. I bought a book written by Lady S Kibibi, in which she chronicles a few of her experiences as a transgender sex worker in Canada and Côte d’Ivoire. I danced with people from Haiti, Kenya, and Ghana. I shared my ideas on what it means to find pleasure, be personally free, and raise liberated children in today’s world. I walked in on a session where someone was teaching people how to put condoms on a phallus (flesh or silicone) with just their lips. It was spectacular.

What struck me the most, though, was a remark by a young woman who attended the session on Women Loving Women: Exploring Pleasure. One of the facilitators was sharing her journey to understanding and accepting her asexual identity, and this young woman asked in a voice full of surprise, "So you’re saying it is really possible to love someone and not want to have sex with them?" Many voices chorused, "Yes, it is."

At the end of the session, as everyone in the room took turns commenting on the discussion, this young woman said: "For the first time in my life, I feel normal."

Normal.

I recently subscribed to an image-focused news service called Beautiful News. Their most recent newsletter contained an infographic titled Far More Unites Us Than Divides Us. It was based on a 2019 study of 85,000 people across countries, religions, economic status, genders, age groups and education levels. The lowest rate of commonality was evident across countries at 84%. The other categories showed convergences of 91%, 96%, and 97%.

I was honestly a bit surprised by the numbers. If we share so much, how do we manage to fixate so aggressively on categories of difference? Why do we sustain social structures, institutions and widespread practices that result in people going through their whole lives feeling "abnormal" and suffering for it? How do we manage to amplify and denigrate difference so much that people end up ill, ostracised, and even dead? Why do we weaponise difference against people who are actually extremely similar to us?

When I introduced one of my closest family members to my female partner last year (and thus effectively "came out") over the phone, my relative took some time to think about it. "I’ll call you back," she said. An hour later, she called back and said: "You know what? I thought about it, and it actually doesn’t make that much of a difference." And she was right. Love is normal. Lust is normal. Sex is normal. Intimacy is normal. Companionship is normal. Affection is normal.

We are all products of our environments, socialisation and conditioning. Most of us grow up thinking that "normal" is what we see everyday, everywhere around us. And we are correct. But it is important to remember that "normal" is not only what we have always known. Normal is also what we do not know, have never encountered, or struggle to understand.

In a world of seven billion people, there are infinite possibilities for difference. Difference is normal. Once we accept this, it makes it so much easier to fixate not only on the 3% to 16% that differentiates us. It allows us to also see the 97% to 84% that connects us. It enables us to see the full picture, which is that we are all 100% human.

It shouldn’t be the case that people spend their whole lives not knowing they are normal, but this is what happens when we misunderstand and misrepresent difference. I like to think that the words "normal", "typical" and "common" do not mean the same things, even though most people use them interchangeably. For instance, violence is common, but it is not normal. Platypuses are not common or typical, yet they are quite normal.

The Adventures Live! festival was not typical, but it was completely normal. And I’m so glad to have been able to witness a quiet young woman’s realisation that she is really and truly normal, just like everybody else.

Till next year,

Want to receive my newsletter in your inbox?

Follow my weekly newsletter to receive notes, thoughts, and questions on the topic of Othering and our shared humanity.

Want to receive my newsletter in your inbox?

Follow my weekly newsletter to receive notes, thoughts, and questions on the topic of Othering and our shared humanity.