I am an alcoholic. Let’s get that part out of the way. I don’t say it to shock. I don’t say it to garner sympathy. It’s just the truth.

If you’d seen the inside of my apartment a few months ago, you’d have seen a chaotic mess – a floor covered with empty bottles and cans, with no sense of order or peace. I turned my own home into a place that mirrored my personal life and the wreck I was making of my health.

I started drinking at 16. That’s not unusual in Australia, where the legal drinking age is 18 but the social drinking age is much lower. It’s considered a normal way to live – start having a few drinks with your mates after school, perhaps sharing a six pack, and it forms hard-to-shake habits early on. I’ve been drinking for so long now I can’t remember a single sober celebration. I’ve been drunk on every birthday, every holiday. Certainly every Christmas.

I first recognised that I had a problem when I was in law school, in my early 20s. I was struggling with the weight of my class load and my anxiety and worries about what to do with my life. The stress started to encourage my drinking. The regular glasses of wine or beer at the university bar turned into late-night glasses of scotch alone in my room. But it became far more dangerous when I began carrying a hip flask of that cheap scotch to class with me in the morning, taking a quick sip between lectures, just to have the courage to get through the day. And it didn’t improve from there. It has been at least a decade since I started down that path.

My turning point

I have lost so many people through my drinking. When I look back on the end of my six-year relationship with an amazing woman I had started to build a life and a sense of purpose with, I know my drinking was a contributing factor. It made me distant and impossible to reach, a haze of drunkenness and anger and sadness separating me from her.

I would tell you stories, but they’re clouded and confused in my mind. I know I passed out one New Year’s Eve. I know that I was wasted through every key moment and that the missing pieces are missing because of my choices.

I sobered up on 8 June 2019. It’s a date that is burned into my memory. A date I am planning to have tattooed on my skin as a permanent reminder of my turning point – and a warning not to go back. There are many explanations for why I quit. I could tell you about discovering my friends had a group chat to share how scared and worried they were. Or that I was simply exhausted and could no longer summon the strength to face my ongoing hangovers.

But the most pressing reason is that the night before, I had been drunk enough and miserable enough to begin seriously considering self-harm. I had finally scared myself enough to make a change. I woke up the next morning, surrounded by empty bottles, and realised that there was only one way the spiral of my alcohol abuse could end. I knew it wouldn’t be pretty.

That first morning when I finally stared down my drinking and refused to flinch away, I poured several bottles of spirits and an entire case of wine down my kitchen sink in a manic rush to expel it from my apartment – and from my life. I threw up in the same sink, partly from the residual alcohol in my system, partly because I was horrified at who I had become. I was desperately sick to my stomach at the thought of facing the world and my life sober. I started messaging my friends, telling them that I had finally dried out.

I began counting off the days, one by one, first white-knuckling it to 30. Then to 60. Then 100. I reached 165 days in late November, and I had expected it all to feel easier at that point. But every morning as I wake up, I feel that tug. I know I still want to drink – no more than ever, but certainly no less.

Facing Christmas in Australia without the buffer of alcohol

I’ve never found the holidays particularly easy. They bring up memories I’d much rather forget of a difficult childhood and an abusive parent. This Christmas, I’ll be facing the festivities without having the buffer of gin, vodka, beer, wine, or any other protective shield.

Christmas in Australia is a little different to what you might have seen in Hollywood movies. We don’t have Frosty the Snowman, and our ongoing bushfire crisis means a yule log burning would be in terribly bad taste. Christmas Day is blisteringly hot. It’s more traditional to eat shrimp together and start drinking as soon as it’s daylight, staving off the heat and the pressure with cold food and alcohol.

During December, the last items on my to-do list pile up, the hot days last longer, and the stresses seem to mount. The Aussie heat starts to feel like a pressure cooker, and the social obligations don’t help. I can barely remember most of the Christmas parties I’ve ever attended. They’re obscured in a haze of whatever was being served, with any indiscretions considered forgivable because it was “just that time of year”.

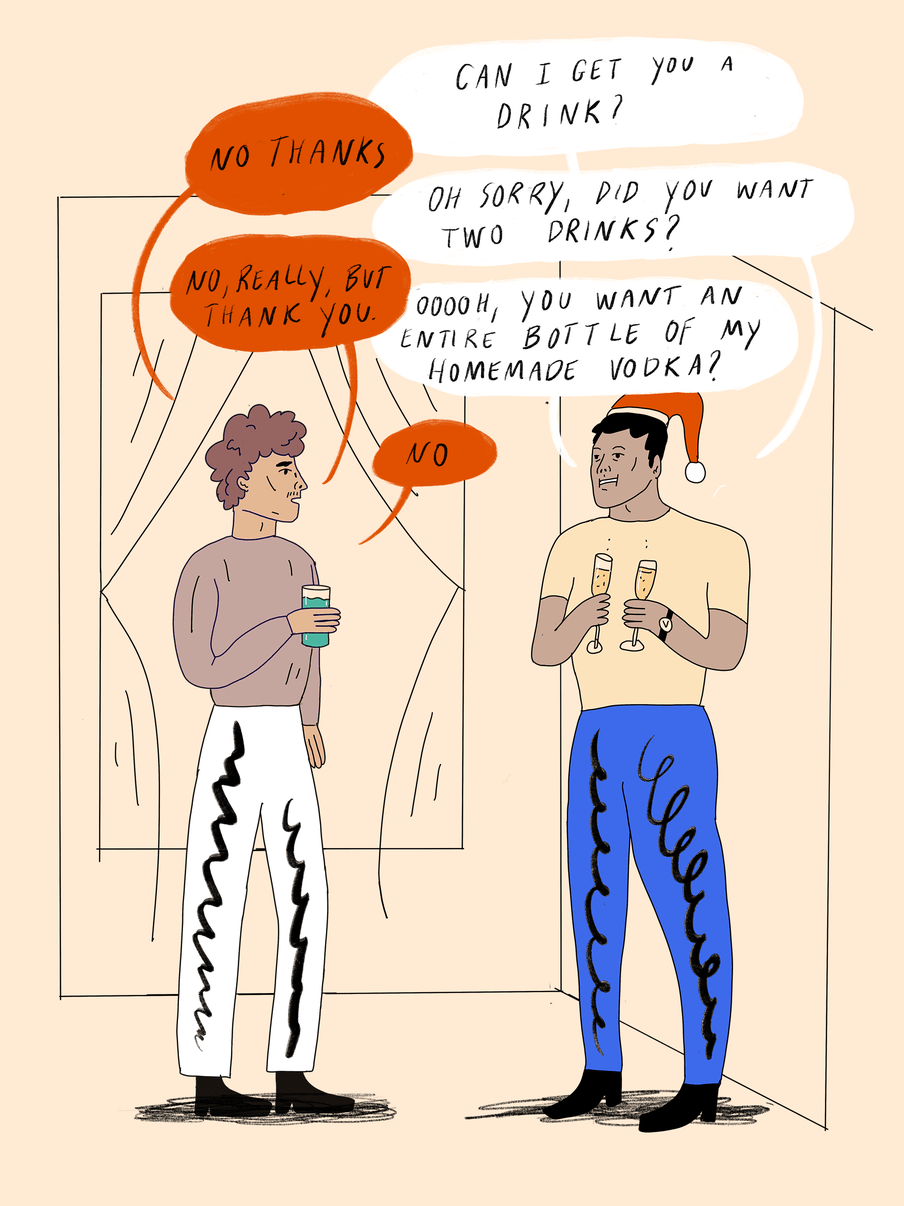

This holiday season, the invitations stare at me with a challenge. When you quit drinking, it becomes an uncomfortable part of your interactions. People often respond quite negatively when you refuse to share a drink with them. They’ll push and needle you to have one – just one. They’ll say they could never quit drinking. They’ll ask why you aren’t joining the fun. Are you allergic to it? Did you just have too big a session the night before? Are you on a weight-loss kick?

It’s a series of questions that eventually push me to admit that I am, in fact, a recovering alcoholic to the embarrassment and discomfort of the interrogator. Whenever that admission is forced out of me, the tension and awkwardness becomes palpable. People don’t really want to know about it. They don’t want to hear the story. They don’t want to face it, perhaps because it might make them ask some difficult questions about how much drinking there is around them and what role they play in enabling it. And maybe they just don’t want to take a look at themselves – at their own habits, their own drinking.

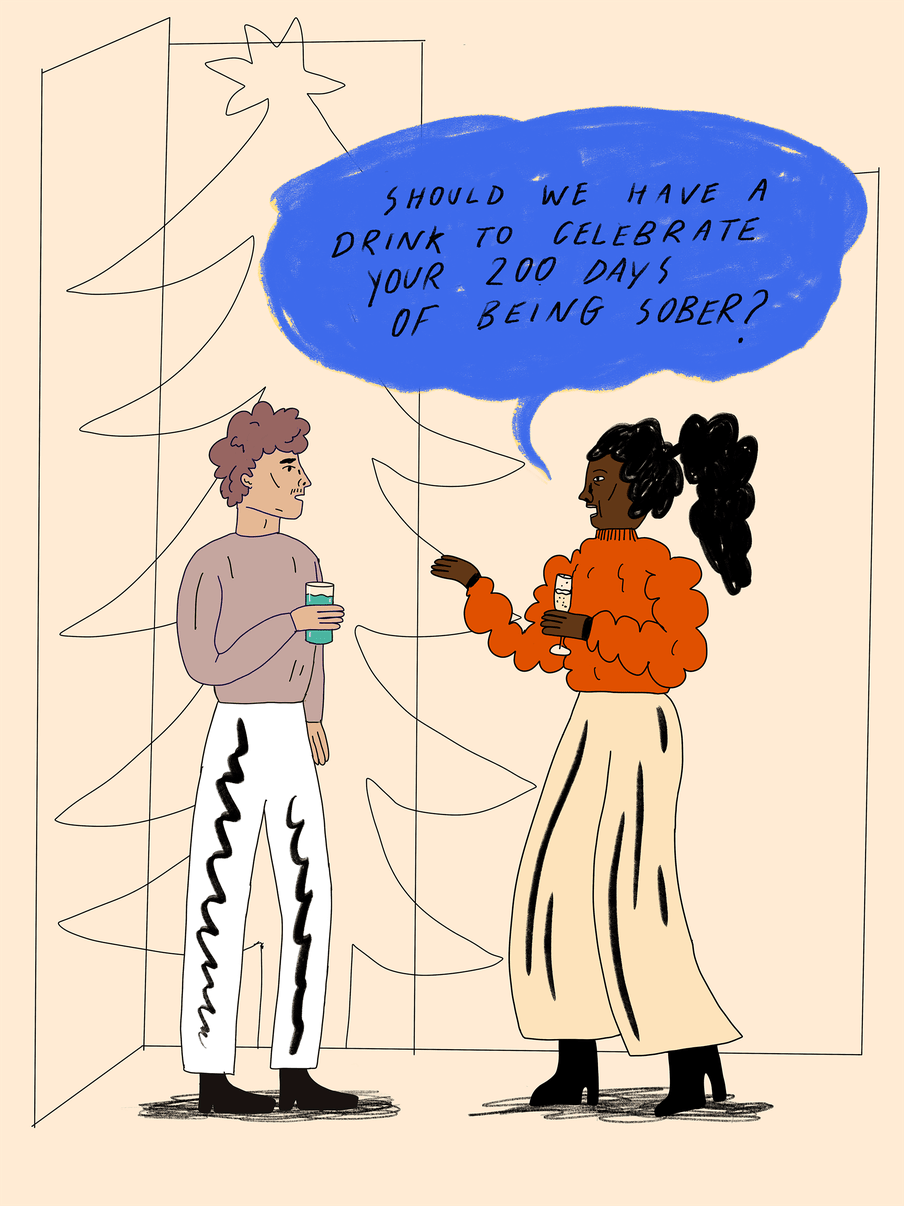

My 200th day sober

On 26 December this year, I will be celebrating my 200th day of sobriety. It still feels impossibly far away, but it’s so much closer now than I ever thought I could be. I’ll mark the occasion as quietly as I can. Although solitude is a difficult, painful and scary part of sobriety, I’ll preferably mark it alone.

I want to feel the honest weight of my sobriety, a weight that I can claim as a sole victory. I want to pause to consider how far I’ve come, with the space to reflect that can only come from being alone. I won’t block my friends out of the occasion, but I think there’s a certain beauty in being comfortable enough with my own sober company to be able to appreciate my growth and progress.

Reaching that point is still at risk, of course. I’m not quite there yet, and the days between it stretch out, full of what I know will be temptations, difficult moments, and the ever-present thought that perhaps just one drink wouldn’t be all that bad. But I think I’ll be fine in the end. At least I hope so.

I find myself thinking about lost things. About lost time, and lost years, and other lost Christmases, too drunk to be able to feel anything. I would like to change the way I see the holidays, and maybe my first sober holiday season will help. It could be a chance to create new memories. It could be a fresh start.

If any of the issues raised in this piece resonate with you or someone you know, please know you don’t have to suffer in silence. Seek help.