On 5 December 2017, Thomas Spijkerboer was glancing through European commission Decision C(2015) 7293 in his office in Lund, Sweden. The document concerned a fund created to address “the root causes” of migration and displacement in Africa. Not exactly light reading, but nothing out of the ordinary for a professor of migration law. But then Spijkerboer came to page nine.

“The countries referred to in paragraph 4 of Article 1 … ”

He flipped back to the previous section: Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Libya, Nigeria, Niger, Senegal, Kenya, Somalia, Algeria ... The list went on and on until it named half the African continent.

“ ... are considered to be in a crisis situation in the sense of paragraph 2 of Article 90 of the Rules of Application … ”

Wait, what? Half of Africa in crisis? It’s not often you encounter such terrible news in a dry legal text. Just how long was this tragic situation expected to last?

“ … for the duration of the Trust Fund.”

Spijkerboer was dumbfounded. “Makes my day,” he scribbled in his notebook, with more than a hint of irony.

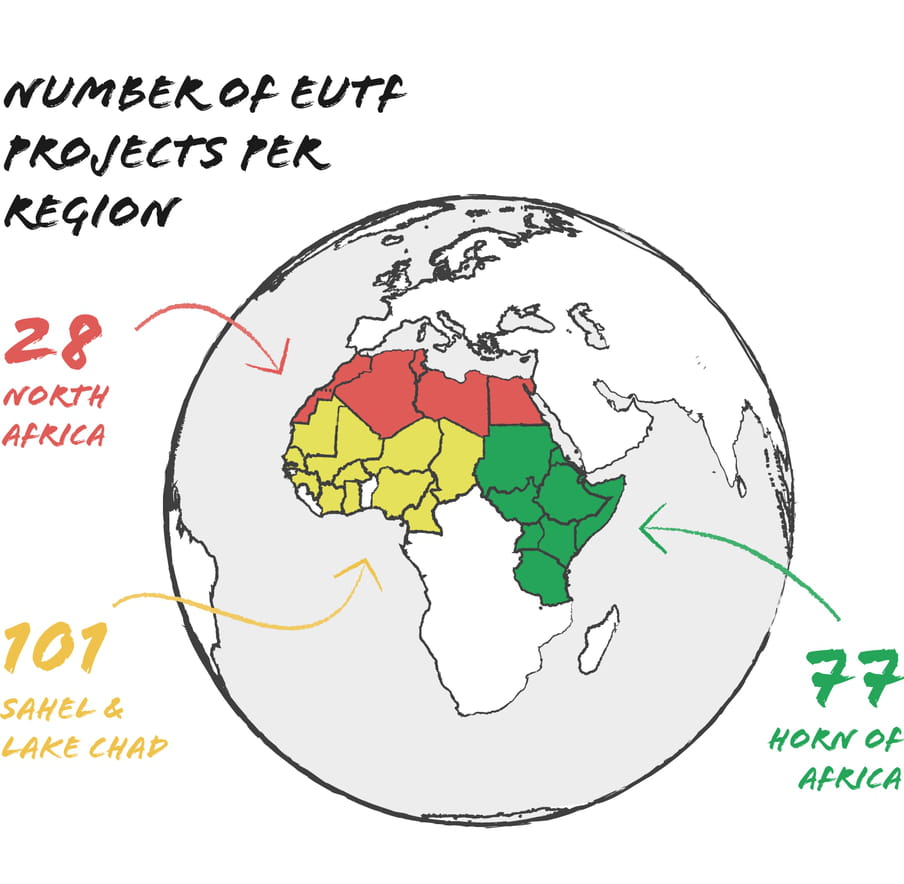

Because there’s a lot at stake here. The document Spijkerboer was reading provides the legal basis for one of the European Union’s (EU) largest and most significant migration funds: the European Trust Fund in Africa (EUTF). Within the space of three years, the EUTF has spent €4.6bn on migration projects in Africa.

And with that one sentence, tucked away in an obscure legal text, the EU had exempted itself from its own regulations. In the event of a crisis, the EU is no longer required to follow public procurement procedures. Necessity knows no law.

A fund founded in a hurry

Now, we realise that a story about procurement procedures for an EU migration fund sounds like something you’d find in a specialist journal. And that’s exactly what Spijkerboer, professor of migration law at VU University Amsterdam, initially set out to write. Together with Elies Steyger, professor of European administrative law at VU, he embarked on an expedition through the legal wilderness of “the Emergency Trust Fund for stability and addressing root causes of irregular migration and displaced persons in Africa”. (It doesn’t exactly roll off the tongue – you can see why it’s known as the EUTF.)

Spijkerboer and Steyger wanted to understand how contracts for EUTF-funded projects are awarded. Who gets the money and why?

However, they soon realised that this seemingly straightforward question actually reveals a fundamental problem with EU migration policy – one with major real-world consequences.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. It’s important to know a little bit about how the EUTF was founded. The short version: it was done in a hurry.

It was the summer of 2015, the height of what Europe would come to call the “refugee crisis”. Migrant boats were arriving daily on the Greek islands, one rubber dinghy after another had sunk off the coast of Italy, and thousands of people were trekking through eastern Europe on foot. Mediterranean governments were overwhelmed by the sheer numbers of people seeking asylum on their shores.

And although most of these asylum seekers came from Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan, the “crisis” also drew attention to migration from Africa, which had remained fairly constant for years. At a summit in Malta, African and European leaders decided that more money was needed to tackle the “root causes” of migration and displacement in Africa. Lots more money. And so the EUTF was born, managed directly by the European commission.

It’s far from transparent how the EU awards all that money

The vast majority of the €4.6bn that has been pumped into the EUTF over the past three years comes from existing EU funds. The rest is made up of contributions from EU member states, Switzerland and Norway. Germany and Italy lead the pack, contributing €182m and €123m respectively.

The EUTF is all over the place: projects aimed at curbing African migration to Europe are lumped together with projects that provide emergency aid during major humanitarian crises. It funds an incredible variety of initiatives: food aid, peace-building projects, border control, awareness campaigns, employment programmes and more.

But the methods for choosing which projects will receive funding remain shrouded in mystery. In the words of the European Court of Auditors, the selection of projects is “not fully consistent and clear”. A study commissioned by the European parliament found “the whole process [is] quite opaque”. Generally speaking, project proposals do not compete openly. In addition, there are no provisions for parliamentary oversight of how the funding is spent. The European parliament has called for more democratic handling of EUTF’s project choices on multiple occasions, but these calls have “largely been ignored”, says Tineke Strik, member of the European parliament (Green party).

Researchers, policymakers, academics and the European commission itself have argued that what the EUTF’s decision-making process lacks in clarity, it makes up for in speed. Rarely has the EU been able to launch projects in Africa so quickly or with such “flexibility”.

So how does EU public procurement work?

Spijkerboer and Steyger wanted to know how this speed was possible. Obtaining funding from the EU is usually a long, drawn-out process involving open calls for tenders.

According to EU regulations, all contracts valued above a certain amount must be published in the Official Journal of the European Union. This gives everyone an equal chance of winning a government contract. “Public procurement is intended to promote competition, ensuring that public money is spent as effectively as possible,” explains Steyger. “The EU must do everything it can to make the procurement process as open, transparent, non-discriminatory and objective as possible.”

During crisis situations, EU grants may be awarded without a call for proposals in the event of emergency. Think: tsunamis, hurricanes, volcanic eruptions

There are a few exceptions to this principle, however, such as defence contracts containing state secrets, or when one party has a legal monopoly.

But there’s another exception, and it’s a big one: during crisis situations, EU grants may be awarded without a call for proposals in the event of “exceptional and duly substantiated emergencies”. Think: tsunamis, hurricanes, volcanic eruptions, and the like.

Of course, this makes perfect sense: if Nepal is hit by an earthquake, you don’t want to have to go through a lengthy procurement process before you can send food, tents or blankets.

The ‘crisis’ in Africa

Back to those EUTF documents. “The fund’s legal basis turned out to be a mishmash of documents,” says Spijkerboer. A legal mess the likes of which is rarely seen in the context of EU bureaucracy. Spijkerboer and Steyger combed through document after document and examined article after article, eventually stumbling on a strange section of text.

"Article 3 Decision C(2015) 7293 final" of 20 October 2015 consists of four unnumbered sentences, each dealing with a completely different issue. “That’s not how a legal document is supposed to be written,” says Spijkerboer. “It keeps people from referring back to the rules you’ve established.”

And yet, tucked away between several unrelated sentences, there’s a startling declaration: the countries that receive EUTF funding “are considered to be in crisis situation in the sense of paragraph 2 of Article 90 of the Rules of Application” for as long as the fund exists.

Article 90 referred to here, however, actually concerns the enforcement of fines, with not a word about crisis situations. Spijkerboer decided to search through all EU procurement regulations for the word ”‘crisis”, finally hitting upon Article 190: an exception clause for earthquakes, tsunamis and other disasters. The EUTF document had omitted a “1” in front of the “90”. Spijkerboer: “They’ve got billions in funding, but they somehow missed a crucial typo in their foundation document? I mean, come on!”

Typos aside, what this means is that EUTF has declared a crisis in all of the countries in which it operates – for as long as it exists. The fund will continue to operate through 2020 at the very least, and there’s already talk of an extension. Because of this so-called crisis, €4.6bn in funding can be allocated without an open call for proposals. In 26 different African countries.

A top official from the European commission informed us that in several African countries there have, in fact, been open calls for tenders for local contracts. This is confirmed by the European commission. “However, the rules don’t actually require us to do so,” the official admitted. “We can allocate funding without calling for tenders if we want to.”

Just let that sink in a minute.

What this means: Europe’s rush to spend money

The question is: why was the EUTF set up in this way? What’s in it for the EU?

Officials working for the EUTF and the European commission were remarkably tight-lipped, even when we spoke off the record. But it’s not hard to imagine why the EU might prefer to act quickly rather than follow normal procurement procedures.

“Migration policy is communication policy,” says one closely involved anonymous source. “Politicians want to be seen as taking swift, decisive action.” A summit in Malta, where the EUTF was established, was the ultimate example of this. It was the height of the refugee crisis and European policymakers were calling for all hands on deck to reduce the numbers of migrants arriving on the shores of the Mediterranean.

Within a single day, world leaders hashed out the framework for the EU-Turkey deal, which gave Turkey €3bn to limit the influx of Syrian refugees. “That caught African leaders off guard,” said the source we spoke to. Now the EU also needed to come up with a deal with Africa “to show that they were also serious about cooperating with [the continent]”. Participants described the resulting negotiations as “an all-night session”.

The outcome was an action plan that was largely symbolic and political in nature, the details of which (read: the actual contents of the programmes to be set up in Africa) were fuzzy or absent entirely. It was therefore crucial for the EU to find a quick and flexible way to actually put the plan into practice.

Their solution: the EUTF. “The idea behind the EUTF was to be able to respond within days, not weeks,” says an adviser to the European parliament.

‘The inclusion of a clause exempting the fund from public procurement was no accident; it was a deliberate choice’

And what better way to hurry things along than by declaring a crisis?

“The inclusion of a clause exempting the fund from public procurement was no accident; it was a deliberate choice,” argues Spijkerboer. This is also confirmed by the European commission. According to a spokesman, the EUTF was set up to allow “a joint and flexible response”, which “has permitted to deliver concrete and swift results on the ground”.

We spoke to other experts on international funds and European law, all of whom agreed that the authors of the document “almost certainly knew what they were doing” and that they had likely “intended” for the clause to be “somewhat hidden”. Spijkerboer adds: “That clause is virtually impossible to find. The only reason to bury a clause like that is if you expect it to cause problems. Problems like, say, angering 26 African governments if they were to find out about it.”

Tensions between the EU and the African Union (AU) were indeed running high at the summit where EUTF was founded. At that particular moment, declaring a state of emergency in 26 countries wouldn’t have been a very smart diplomatic move.

So, what are the consequences? ‘A migration cartel’

But there’s more to this story. In addition to its bureaucratic and diplomatic repercussions, this clause has had major real-world consequences.

When Spijkerboer compiled a list of all EUTF migration management projects (worth a total of €1.7bn), he found that 65% of this funding winds up in the hands of only five organisations: the UN agencies for migration and refugees (IOM and UNHCR, respectively), German development agency GIZ, the Italian government, and French organisation Civipol. IOM receives by far the most money: 22%, nearly a quarter of all funding.

Our own research revealed that this percentage is even higher in Nigeria, where 86% of EUTF funding goes to UN and EU agencies.

But why is that?

It’s not the result of some grand conspiracy, but simply because it’s easier for these organisations to gain access to the fund. European development agencies and UN organisations know exactly who holds the reins of power in Brussels, they speak the necessary bureaucratic lingo, and they’re skilled at drafting proposals that meet EU guidelines. Several officials told us that the majority of project proposals are submitted by member states, their development agencies, and UN organisations. This is also provided for in the fund’s founding agreement: Article 10 defines cooperation with member states as the "preferred option" for implementing projects.

‘What we’ve got is a market where government contracts are only awarded to a handful of players’

For example, the German development agency GIZ could run an idea for a new project by the German embassy in Nigeria, who could then take the proposal to the European delegation in Abuja, who could then bring it up with the European commission. If the project later wound up being approved, GIZ might be tasked with implementing it – without other organisations ever getting a chance to compete for the project.

In this way, the bulk of EUTF funding winds up in the hands of UN organisations and agencies run by EU member states rather than international NGOs or African organisations, who could potentially do it just as well or better, or for less money. Of course, there’s no way of knowing whether formal public procurement procedures would help outside organisations to win contracts. Smaller organisations might find it difficult, or even impossible, to meet the high standards set by the EU.

But as things currently stand, these organisations never even get the chance to try. In addition, African countries aren’t even allowed to vote on EUTF projects, but can only sit in as observers at meetings where projects are chosen.

“This is exactly what public procurement law is meant to prevent,” says Spijkerboer. “What we’ve got is a market where government contracts are only awarded to a handful of players.”

Spijkerboer calls it “a cartel”.

Is it legal?

Spijkerboer and Steyger say it’s unacceptable. The EU is violating its own procurement rules.

Under current EU policy, emergency situations must be “duly substantiated”. “But no such justification exists for the EUTF,” says Spijkerboer. “Absolutely no evidence has been provided to support the claim that all 26 African countries are suffering from a crisis that is expected to last for the duration of the fund.”

A generalisation of this kind is also "clearly disproportionate", adds Steyger. The European Court of Auditors also commented that "the crises that the EUTF seeks to address have not been clearly defined for the different regions".

But in stable countries such as Ghana, Senegal or Kenya? A crisis?

Of course, some of the regions that receive EUTF funding are actually in need of emergency help. There are good arguments to be made for skipping public procurement procedures when it comes to providing hunger relief in northern Nigeria or medical care in South Sudan, or to fight terrorism in northern Mali.

But in stable countries such as Ghana, Senegal or Kenya? A crisis?

Since when are projects such as improving border control in Ghana, creating more jobs in Senegal, or helping refugees in Kenya to become more self-reliant a matter of life and death?

And even in countries such as Mali, where the northern region is indeed in crisis, many EUTF-funded projects have no direct link to the actual source of the emergency. Surely there’s no way of framing the improvement of civil registration in Mali – an issue that the government has been putting off for years – as the result of an unforeseen disaster that exempts it from normal procurement procedures?

And is such a crisis clause necessary at all? The European Court of Auditors has responded to this article by saying: "We note that while the EUTF for Africa has, overall, managed to speed up the signing of contracts, other existing emergency instruments are still faster in this regard."

What’s the EU’s response?

When asked to respond, the European commission says it has indeed declared a crisis in 26 African countries. In so doing, the EU is not violating any "legal provisions", writes the spokesman, "provided that the crisis declaration is justified". This would be the case because "most countries eligible" to EUTF money were, when the fund was established in 2015, in emergency situations. The commission continues: "This is why, for the purpose of the instrument, the countries it covers were assimilated to countries in a situation of crisis."

The commission underlines that sometimes public procurement procedures do take place for the EUTF. How often is unclear. The spokesman says that approximately 14% of EUTF money goes to local or international NGOs via EU agencies.

According to the European commission, the fact that most of the money is spent through the member states and their agencies has nothing to do with the crisis clause, but with Article 10 of the fund’s founding agreement. This defines cooperation with member states and their agencies as the "preferred option" for implementing projects. This is, says the spokesman, "to avoid duplicating structure and make the best use of donors’ expertise".

The commission describes the setting up of the EUTF as a response to "the different nature and dimension of crises characterised by their volatility and amplitude in the African continent". Remarkably, the refugee crisis or "migration" is not mentioned in the entire response. While the EUTF’s mission is to "promote stability and contribute to better migration management, including by addressing the root causes of destabilisation, forced displacement and irregular migration".

The commission does not address our questions as to why the crisis clause is so oddly hidden in the legal documents, or as to the typing error in the document.

Whose crisis is this?

The AU failed to respond to repeated requests for a response. We did receive a response from Ferdinand Nwoye, spokesperson for the Nigerian Ministry of Foreign Affairs: “I don’t think there’s any reason to be angry that Europe has declared a crisis in our country. If desperate Nigerians risk their lives to come to Europe, is that not a crisis?”

“In the event of a crisis, it’s obviously important to be able to make funding available as quickly as possible,” said EU parliament member Tineke Strik. “That’s what these types of emergency funds are for. But the EUTF is paradoxical in that it’s an ‘emergency fund’ that has been used for the past four years to set up projects with long-term objectives. It’s a prime example of how the European parliament became sidelined during the refugee crisis of 2015.”

“It’s entirely unclear which, and perhaps more importantly, whose ‘crisis’ the fund is meant to address,” Strik added. “It appears that the repackaging of migration policy as ‘dealing with a crisis’ has enabled member states to exercise extraordinary powers. This is contrary to the principles of the rule of law that the EU is supposed to stand for.”

International aid organisations agree. “Europe’s wider migration policy – including its activities through the EUTF – sometimes creates more problems than it solves,” said Wouter van Dis, migration expert at Oxfam Novib. “For example, through the EUTF, the EU may have indirectly funded ‘security forces’ in Sudan that brutally suppressed peaceful protest marches in Khartoum, resulting in bloodshed. This was certainly shocking news and a major scandal, but it was frankly the result of hasty and ill-considered standing policies.”

The real crisis

When it comes to migration, the EU is by no means unique in its attempt to bypass normal checks and balances and democratic controls by declaring a state of emergency.

Donald Trump did it – as he does so many things – loudly, crudely, and in front of a bunch of cameras. At the beginning of this year, he declared a national emergency along the US-Mexican border in an attempt to gain easy access to funding for his long-promised border wall.

‘The EU still hasn’t got its own house in order, yet somehow they want to promote good governance in Africa? Something tells me that won’t necessarily be a success’

Viktor Orbán did it in Hungary, Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil, Kyriakos Mitsotakis in Greece, and Lenín Moreno in Ecuador. They all claimed the existence of a migration crisis in an attempt to sideline parliament. But with one crucial difference: they did it in their own countries.

No matter what the EU says, this so-called “migration crisis” isn’t an African crisis – it’s a European crisis. A crisis of how much solidarity EU member states owe one another, who is responsible for taking in asylum seekers, and exactly how to go about “protecting our European way of life”.

The real answer to the crisis is in the halls of government in Brussels, not Africa.

The irony doesn’t escape Spijkerboer. “The EU still hasn’t got its own house in order, yet somehow they want to promote good governance in Africa? Something tells me that won’t necessarily be a success.”

The entire response of the European commission can be found here.

This article was translated from the Dutch by Megan Hershey. It was written with the support of the Money Trail project.

Dig deeper

Europe spends billions stopping migration. Good luck figuring out where the money actually goes

How much money exactly does Europe spend trying to curb migration from Nigeria? And what’s it used for? We tried to find out, but Europe certainly doesn’t make it easy. These flashy graphics show you just how complicated the funding is.

Europe spends billions stopping migration. Good luck figuring out where the money actually goes

How much money exactly does Europe spend trying to curb migration from Nigeria? And what’s it used for? We tried to find out, but Europe certainly doesn’t make it easy. These flashy graphics show you just how complicated the funding is.