Eleanor Thom is 34 years old and preparing for her tenth surgery – to prevent her left ovary from pulling towards her uterus.

The comedian and author has endometriosis, a condition which causes a tissue similar to the lining of the uterus to grow in other places, such as the ovaries and fallopian tubes.

For as many as 176 million people worldwide, the disease, which is usually found in the lower abdomen or pelvis, can cause chronic pain and severe discomfort during sex, and threaten fertility.

Thom, author of Private Parts: How To Really Live With Endometriosis, has tried everything since she was diagnosed at 17, including hormonal treatments and surgery. With the former Thom spent months with bald patches, sore teeth and an aching jaw, dry skin, greasy hair, and constant nausea.

After nine operations, recovery is taking longer each time. With her first procedure it took less than two weeks – she could “dance slowly” at her 18th birthday party – but after the second, she was incapacitated for five weeks. Now it takes months, partly due to the build-up of scar tissue.

Thom has been delaying surgery as long as she can by taking painkillers and doing physiotherapy. Both are intended to reduce the amount of pain and trauma her body endures as a result of going under the knife.

“I’m currently managing ludicrous levels of pain,” she says, “but the painkillers have made me quite groggy so forgive me if I can’t find the words.”

The success of surgery often comes down to the skill and expertise of the surgeon. Even when deemed successful, surgery does not eradicate the disease. 20% of women who participated in a study led by researchers in Australia and the UK reported no improvement after surgery. In a Chinese study, 50% of women were back for more surgery after five years.

Pain consultant Winston de Mello says the best surgical results are experienced by those who enter the operating theatre in a calm state of mind – a difficult prospect given the high levels of pain sufferers endure.

“The more psychologically distressed you are, the less likely you are to get benefit from nerve blocks or surgery,” he said. “It’s like putting a roof on a house without foundations. Surgery [becomes] very fraught with chronic pain.”

Christian Becker, gynaecologist and co-director of the Endometriosis Care Centre in the United Kingdom, points out that 30% of laparoscopies – the most common form of endometriosis surgery – provide short-term placebo relief rather than a long-term cure.

“A lot of the women we see also have chronic pelvic pain. A chronic pain condition is much more difficult to get rid of, even if you cut out or burn away the endometriosis tissue, due to inflammation in the bowel or bladder, or muscular spasms. So we’re not getting on top of the pain and that’s why women are having repeated surgery after short intervals.”

There are many questions that Thom’s story triggers: why does suffering from endometriosis persist on such an astonishing scale? What is it about the nature of the disease, pain management, or the medical and health research establishment itself that could help explain the prevalence of chronic pelvic pain?

A quick online search reveals that there are many people who attest that they have been operated on without being given a proper explanation about the nature of the surgery, or its variable success rate. Could there be a link between treatment of pain and gender? In other words, does the medical community take a gendered approach to pain and could this help us understanding the treatment of endometriosis, more specifically?

Clinicians have long held onto the belief by 17th century French philosopher René Descartes that humans are “bodily machines” that can be fixed. It wasn’t until the latter half of the 20th century, when the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) recognised that pain was influenced not only by biological but also psychological and sociological factors, that the default option of surgery as a way to ‘fix’ the body started to decrease.

The IASP only has one definition of pain, first published in 1979: “An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage”.

This definition doesn’t mention gender identity, and nor does the revised version due to be published this year. Yet there is a growing body of empirical evidence which shows that not only do men and women feel pain differently, they are also treated differently.

"We found that the most plausible explanation for the bias is the enduring assumptions about the dominant role of males, and unimportance of variation in female genitalia" - Malin Ah-King, evolutionary biologist.

A 2001 study called “The Girl Who Cried Pain: A Bias Against Women in the Treatment of Pain” showed that women are “undertreated”: they are less likely than men to be given a health exam when complaining about chest pain and less likely to be given medical relief after having the same procedure as a man.

Yentl Syndrome refers to the documented phenomenon of women having to “prove” they feel as much pain as men to receive “aggressive” treatment. Even in countries that otherwise have a reputation for being egalitarian, gender biases play out. A 2014 Swedish study found that women waited significantly longer than men to see an emergency doctor, with their complaints less frequently classified as urgent. Even when they do see a doctor, women are more likely to be given a sedative, while men are more likely to be given a painkiller.

The lived experience of endometriosis sufferers confirms what the research finds. Thom says she and other women have been told that their pain will “go away eventually”; that they need to take over-the-counter painkillers; that they need to relax, have a glass of wine or become pregnant then hormones released during pregnancy will “sort them out”.

Faced with a lack of options, alternative remedies have become big business for women with genital-related pain, as they turn to aloe vera topical gels, vaginal steaming, and chemical-free tampons in a desperate search for relief.

Medical treatment is also not universal for women. In the UK, black women are five times as likely to die in childbirth and in the US, the same demographic are two to six times more likely to die from complications during pregnancy. While the causes of death are complex, US researchers did point to the “quality of prenatal delivery and postpartum care” to explain the racial differences in maternal mortality rates.

Data on women’s sexual and reproductive health overall tends to be limited, much more so for women of colour and non-binary people. Similarly, the best-cited research is based on the experiences of women in the west, though language barriers also in part explain the limited breadth of evidence.

The treatment of women’s pain is not to be confused with overall health outcomes. All over the world, women outlive men, but the World Health Organisation puts this health gap down to “behaviours associated with male norms of risk-taking and adventure” and “greater exposure to physical and chemical hazards”.

There is no drug or treatment specifically designed for endometriosis. Hormonal treatments such as the coil and the pill were developed for sexual and reproductive health, and other medication such as Anastrozole, were initially developed for women with breast cancer. GnRH, which sent Thom’s body overnight into the pseudo-menopause – twice – has been used to treat women with endometriosis for at least 20 years.

Becker suggests there are medical advances in the pipeline, including some endometriosis-specific drugs in early-phase trials. He also talks about the development of a new dataset which would allow researchers around the world to collect and process data samples according to universally recognised standards, allowing healthcare practitioners to better understand the disease, instead of comparing studies with small sample sizes and inconsistent data.

This improved understanding is crucial, Becker says. It could lead to diagnosing a patient without surgery thanks to a ‘biomarker’, such as a urine or blood test. Or provide insight into the three types of the condition and the drugs could be used to treat them.

“If you look at breast cancer 40 years ago, there were just one or two treatments, and now there are sub-groups of the disease which have more specific treatments,” he says. “With endometriosis, we throw one thing at everything and assume it’s just one condition and it probably isn’t.”

The gap in understanding cannot be bridged without research funding, and if women in pain are not being taken seriously, neither is there serious investment in endometriosis research or, more broadly, in female scientists who are more likely to recognise it as an issue.

In March of this year, Reuters reported on a study that found that in the US, female scientists get smaller first-time grants than their male counterparts.

In 2015 it was revealed that less than $1 a year is spent on research per woman who has endometriosis in the US, compared to diabetes, which receives more than $1bn every year from the National Institutes of Health. And in 2013, a study in the British Medical Journal found that over a 14-year period, between 1997 and 2010, 80% of money for research of infectious diseases in UK institutions was awarded to men. Some of the biggest investors in health research were also the worst culprits with researchers adding that there were “large differences in median funding amounts for men and women researchers in investments by the European Commission and the [British] Medical Research Council.”

Despite the latter study’s focus on funding to infectious disease, the same trend is seen with non-communicable diseases. The difference between endometriosis and diabetes or asthma, which all have similar number of sufferers, is that endometriosis only affects women. “It’s not ‘sexy’ to talk about women’s pain and periods,” acknowledges Becker.

Spending money on research could save money long term. Lost productivity, combined with endometriosis treatment, is a major economic burden. The UK foots a bill of $10.5 billion a year in treatment, loss of work and healthcare costs, while in the US treating the disease costs the economy $22 billion a year.

The cost to society can be measured, but the cost to the individual often remains invisible. Thom says she has not been comfortable in her body since she was 17. While going through the pseudo-menopause, she dropped out of university and broke up with her partner. In her book, she writes about her dreams “of croissants and high heels, of dancing without the consequences, of trampolines and ice skating, of long walks and spinning around until I’m dizzy with the children I love. I dream of lovers and sex and someone to hold my hand.”

Not only is women’s pain often dismissed or underestimated, there is also a lack of knowledge about the causes of pain and about women’s bodies more generally. "Females are excluded from animal and human studies," researchers at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston concluded in 2014 . In the same year, answering the question "why do scientists ignore female genitalia?" evolutionary biologist and gender researcher Malin Ah-King was quoted as saying: “We found that the most plausible explanation for the bias is the enduring assumptions about the dominant role of males, and unimportance of variation in female genitalia” .

The medical establishment has begun to think differently about pelvic pain management, introducing the four p’s: patient education; pain modification; physical therapy and pelvic floor work; and psychological and psychosexual therapy support.

“Ideally endometriosis patients should be treated in centres of expertise, with a multi-disciplinary and holistic approach,” says Becker. “I’m not saying we can cure everybody – it’s a chronic condition – but it’s better to have someone who understands the condition and symptoms than some private practice surgeon who is good at cutting things out.”

Thom is “disappointed” she has to have another operation, but says she’s not lost hope.

“The more we increase awareness of women’s experiences in all areas of health and the more we talk, the better this will all become, and there will be more advocates saying, ‘We can’t leave women like this.’”

“People will see that it’s wrong on a wider scale – not just because it’s their sister, aunt or cousin. That will then change how the medical system approaches women’s pain and women will less likely be dismissed.”

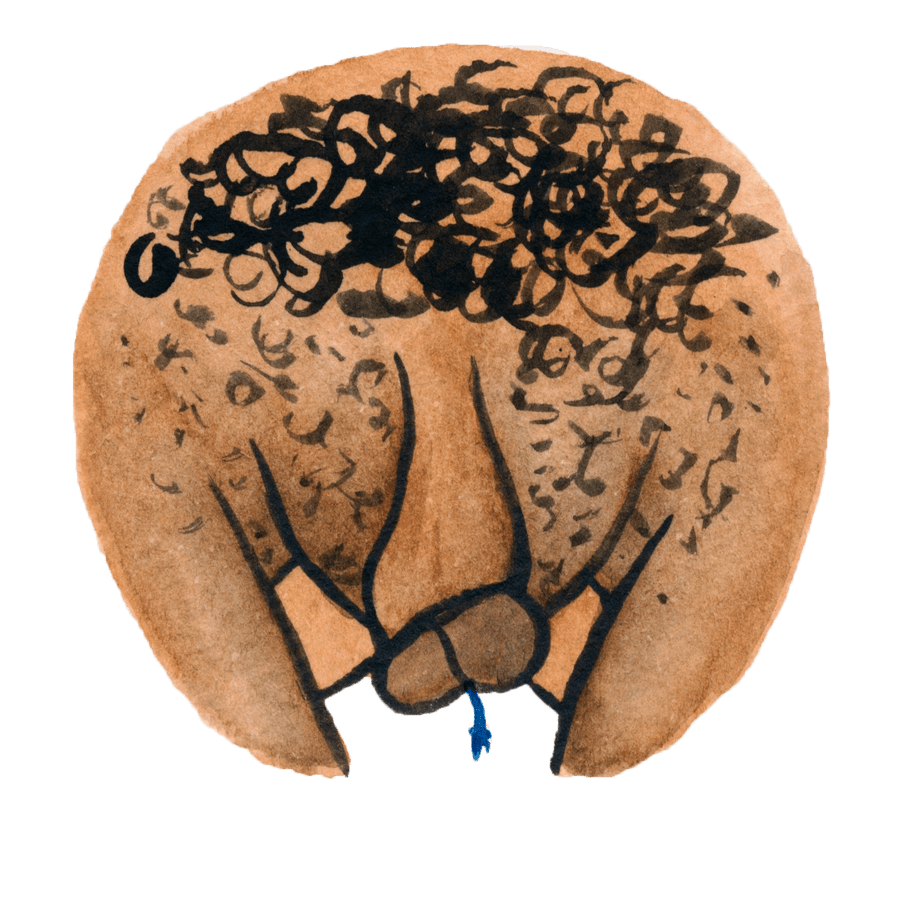

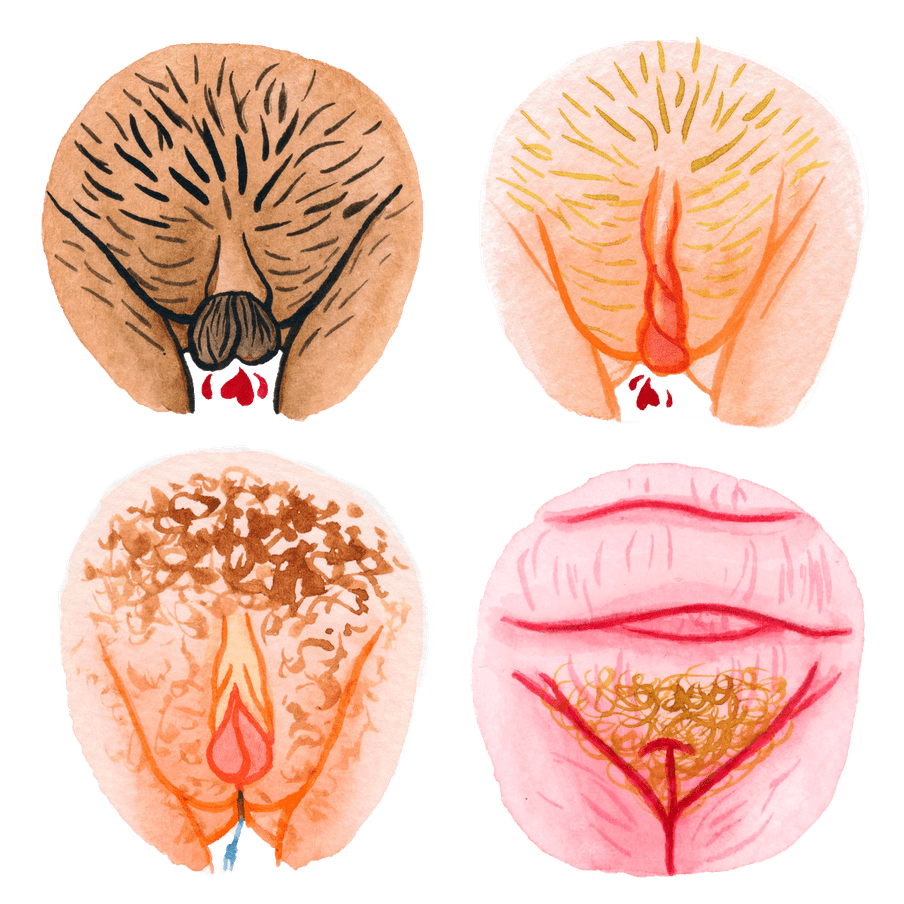

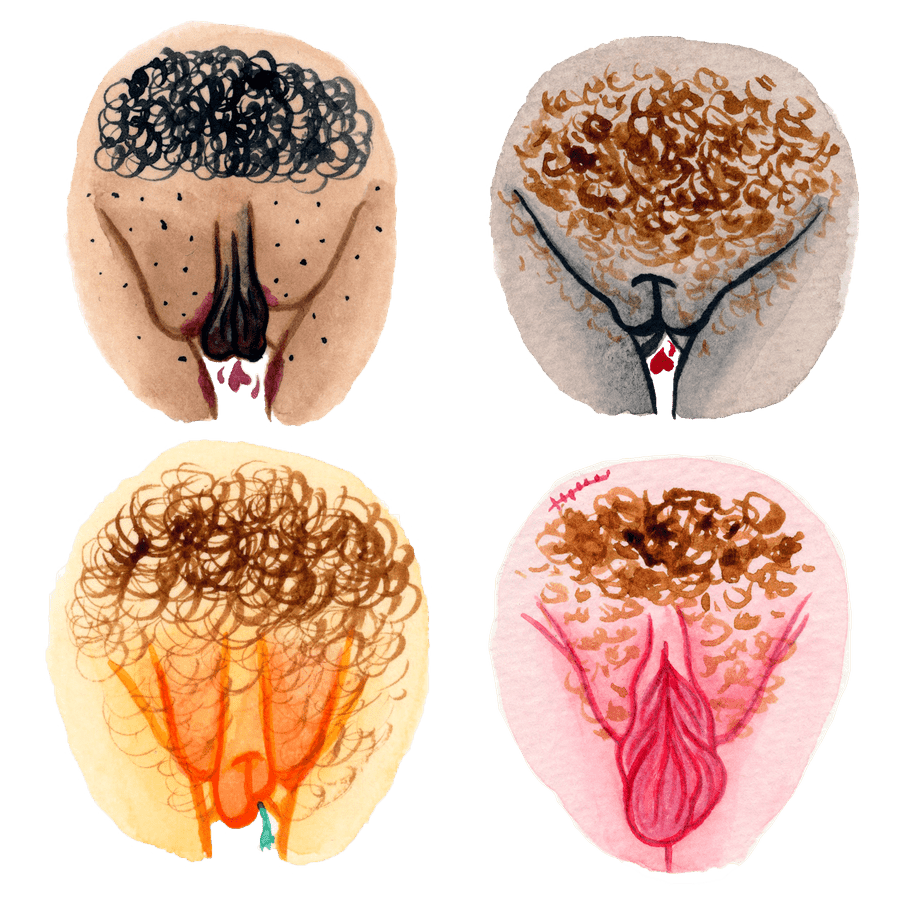

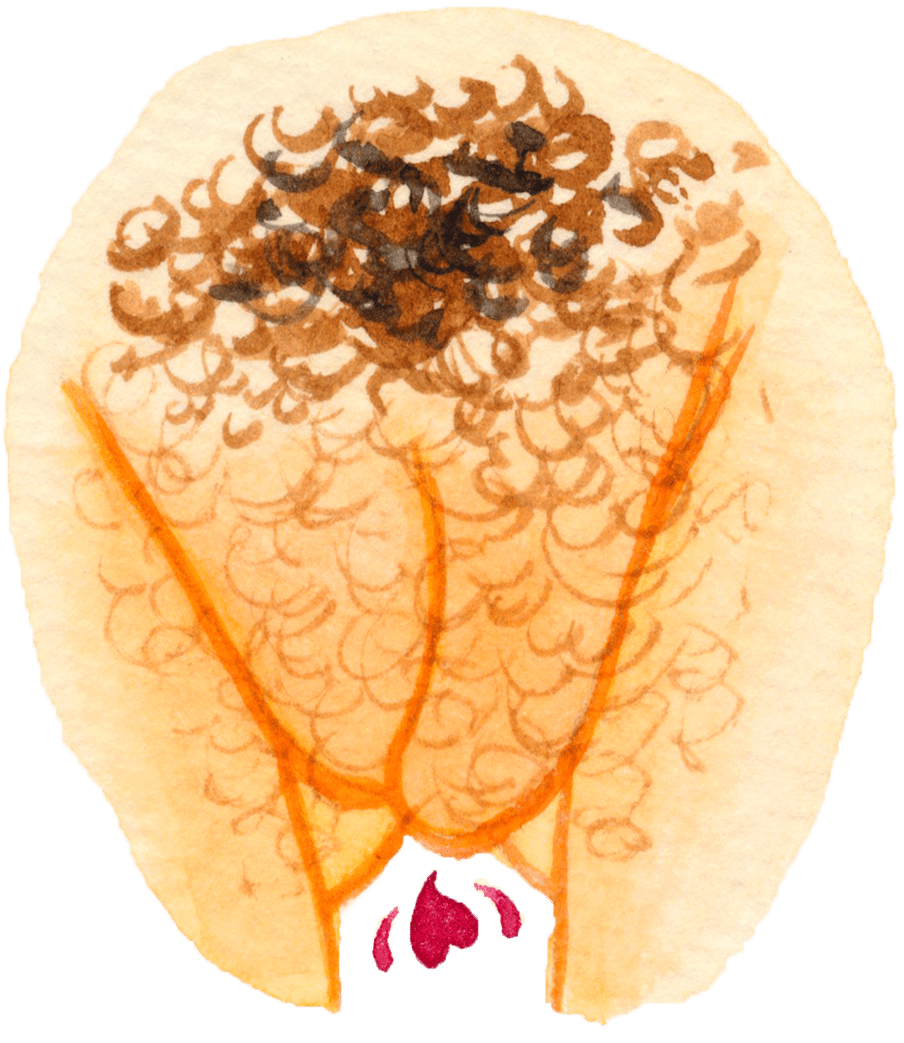

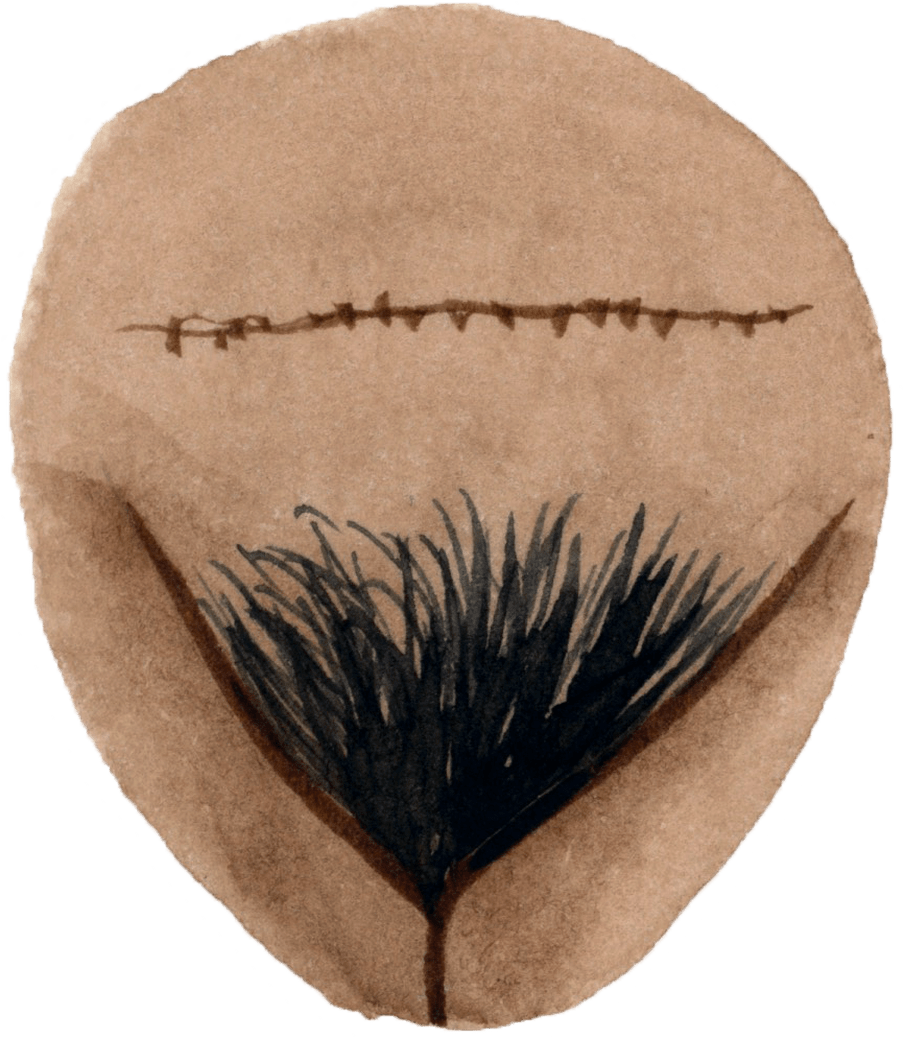

About the images

In 2016 illustrator Hilde Atalanta created The Vulva Gallery – an educational platform centred around illustrated vulva portraits and personal stories – in order to break the taboo surrounding the topic. The project, which has now also become a book, aims to celebrate the vulva in its uniqueness by contradicting the unrealistic image that popular media, magazines, mainstream porn, or even biology books give. Atalanta manages to achieve multiple goals at once: to raise awareness about body positivity and body diversity, to inspire and empower individuals by sharing personal stories, and to provide information on anatomy and sexual health. (Lise Straatsma, image editor)

About the images

In 2016 illustrator Hilde Atalanta created The Vulva Gallery – an educational platform centred around illustrated vulva portraits and personal stories – in order to break the taboo surrounding the topic. The project, which has now also become a book, aims to celebrate the vulva in its uniqueness by contradicting the unrealistic image that popular media, magazines, mainstream porn, or even biology books give. Atalanta manages to achieve multiple goals at once: to raise awareness about body positivity and body diversity, to inspire and empower individuals by sharing personal stories, and to provide information on anatomy and sexual health. (Lise Straatsma, image editor)