Manal Al-Sharif was wearing sweatpants and a Mickey Mouse T-shirt when the police arrived at 2am. They banged on the door of her home so hard that the frame shook. The previous day, at the wheel of her brother’s car, Al-Sharif had been pulled over by traffic police – it was 2011, and still illegal in Saudi Arabia for Saudi women to drive.

As she was taken away to the police station, Al-Sharif had no idea that a colleague was live-tweeting her arrest. Omar Al-Johani worked at the same oil company, and although they didn’t know each other well, when Al-Johani drove past and saw police at her house, he wanted to help. “People knew what was happening,” Al-Sharif told me, “Twitter saved my life that night.”

Fast forward seven years, and Al-Sharif is on stage at a conference in Norway. This is the moment she chooses to delete her Twitter account, in a public act of protest: “This tool that once saved my life is now being used to put my life and the lives of a lot of human rights activists in danger,” she explained in a video posted to YouTube.

Al-Sharif’s change in attitude is emblematic of a wider shift in attitudes to social media platforms. Facebook, Twitter and WhatsApp were once touted as agents of democratisation, heralded by activists across the world as megaphones for protest. In many countries with a record of repression, these same platforms – previously seen as untouchable by forces of coercion – have compounded activists’ fears of censorship and surveillance.

The balance of power on social media has shifted

Freedom House, a Washington-based democracy index, found that social media channels are becoming “instruments for political distortion and societal control”. Where activists embraced social media as a means to organise and broadcast, repressive regimes have seen the same opportunity to push their own messages.

“In 2009, the internet was this liberating force,” says Allie Funk, a research analyst who works on Freedom House’s annual Freedom on the Net survey. It found that online freedoms have been shrinking for nine consecutive years. “Every single year it seems governments are figuring out how to better use digital technology against their citizens, and they’re doing it in more sophisticated ways,” says Funk.

Instead of just banning Twitter – as happened in both China and Iran – authorities in Saudi have embraced the platform. Previously, Twitter and Facebook had played a crucial role in promoting women’s rights inside the Kingdom.

“Without these social media platforms we wouldn’t have had a voice. On Twitter you could be yourself and speak up,” says Al-Sharif. The online opposition to women activists came mostly from religious Saudis, who attempted to smear them with made-up rumours. “It was a battle, but it was a fair battle. The government was not interfering, other than by blocking our websites. They thought we were just kids, playing.”

The battle became more sinister in 2017, when the Saudi government took up online bullying. “They began using [social media] effectively, hiring people to tweet, buying bots,” says Al-Sharif. In October 2018, the New York Times reported on a troll farm in the Saudi capital Riyadh, where employees were tasked to intervene in online conversations on themes including the war in Yemen and women’s rights.

Employees would be sent lists of people to threaten, insult and intimidate; daily tweet quotas to fill; and pro-government messages.

Al-Sharif relocated to Australia, but physical distance was not enough to escape harassment. When Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi was murdered in Istanbul in October 2018, suddenly the death threats Al-Sharif had been receiving didn’t feel so hollow.

Just 23 days after Khashoggi’s disappearance, Al-Sharif made her decision: “If the same tools we joined for our liberation are being used to oppress us and undermine us, and used to spread fake news and hate, I’m out of these platforms,” she said.

Calling in the cyber troops

Other authoritarian states have adopted similar tactics, deploying the social media platforms that once jeopardised their power. The Global Disinformation Order. A September 2019 report from Oxford Internet Institute at Oxford University, surveyed social media manipulation in 70 countries. It found evidence of 26 authoritarian states harnessing social channels to suppress freedom of expression, discredit critics and drown out political dissent.

Saudi Arabia ranked among nine of those 26 countries where researchers found signs of “high cyber troop activity”. Substantial resources are allocated to “psychological operations or information warfare” and “full-time staff dedicated to shaping the information space”.

Egypt, where the use of Facebook and Twitter in the 2011 uprisings was dubbed "social media revolution", is another offender. In the early years of social media, videos of police torture posted to YouTube sparked widespread anger and street demonstrations. Activists’ path from screens to streets prompted researchers to describe Facebook as a "liberation technology".

In truth, Egypt demonstrates how activists’ success on social media was contingent on the technological backwardness of the authoritarian regimes they opposed. Former president Hosni Mubarak was one of the old guard, a generation of leaders who failed to see the significance of protest on social media: “Let them play,” he told a television interviewer, just weeks before protesters stripped him of power.

His successor, President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, has overseen a tactical shift. “Whereas Mubarak had largely ignored the Internet, the current regime uses the internet in a much better way,” says Wael Ghonim, a former Google executive turned activist, who created the Facebook page said to have sparked the country’s revolution.

Today, Egyptian authorities are “drowning out dissident voices amidst its own propaganda and also conducting a campaign of terrorising those who speak out online,” he says.

Locking up online dissenters in Vietnam

Authoritarian regimes that fail to intimidate activists online have a simple fall-back strategy: arrest them. According to Freedom House, 71% of internet users live in countries where people have been arrested for what they post.

“We are seeing the targeting of individual activists, particularly those with large social media profiles or who are well-respected within their community,” says Adam Shapiro of Frontline Defenders, an organisation that tracks activists’ arrests. “In the Gulf or the Middle East, it’s more likely political posts [that lead to arrest],” he told me, speaking from New York. “In Vietnam - one of the more repressive governments in Asia - it can be anything critical. Even complaining about the price of food, can get you in trouble.”

Vietnamese authorities were especially busy in November 2019. On the 5th, Nguyen Van Nghiem (known online as “Dr Haircut”) was charged with defaming the People’s government – becoming the 18th Facebook user to be arrested this year. “His video clips seemed normal to me, though some were a little bit critical,” his wife said in an interview with Radio Free Asia.

The effectiveness of China’s so-called “Great Firewall” proved the former US president Bill Clinton wrong.

Two days later, environmental activist Nguyen Ngoc Anh lost his appeal against a six-year prison term for criticising the government on Facebook, where he urged people to take part in peaceful protests. Human Rights Watch reported that Anh blogged to criticise environmental damage caused by a 2016 toxic waste spill, the lack of free choice in the 2016 elections and his concern for the welfare of political prisoners in Vietnamese jails.

On 15 November, Nguyen Nang Tinh, a 43-year-old music teacher, was sentenced to 11 years in jail on charges of "making and spreading anti-state information and materials" on Facebook. In his defence, Tinh said the Facebook account in question did not belong to him.

Asia’s authoritarian trend

China’s online censorship is a benchmark for governments across Asia. “Ten years ago you didn’t see the prosecution of people solely for online expression,” Nicholas Bequelin of Amnesty Asia said, speaking from Bangkok. “As public opinion has increasingly moved online, governments have followed suit. They’re trying to regulate this space in the same way they regulate other spaces.”

For years, western governments were convinced that attempts to restrict online speech were destined to fail, an attitude summed up in 2000 when US president Bill Clinton sarcastically wished Chinese authorities “good luck” in controlling online speech: “That’s sort of like trying to nail jello to the wall,” Clinton said, famously.

Today, China’s so-called “Great Firewall” has proved the former US President wrong. “China has shown you can tame the internet; they have demonstrated that [online] censorship is actually do-able,” says Belquelin, who argues that China’s restrictive internet policy has influenced other governments in the region.

Researchers worry that advances in artificial intelligence will enable governments to invest in mass surveillance tools, making it easier to comb social media for dissent. “Now they can find every single needle in a haystack that they don’t like,” says Funk.

Criminalisation of government criticism on social media is a trend creeping across continents, according to Shapiro. “One of the other things we’re starting to see is this trend is extending beyond what we’d consider to be authoritarian governments.”

He points to Turkey, where scores of social media users have been arrested for criticising President Erdogan’s military operations in Syria. European Union member states are not immune: in Croatia, journalist Gordan Duhacek was fined in September after he published a satirical anti-government poem, The Crab of Velebit, on Twitter to draw attention to environmental issues.

Pulling the plug: internet shutdowns

A fail-safe option to silence critical voices is to shut down the internet altogether. When Iran’s government abolished petrol subsidies in November, causing prices to rise by at least 50%, protests erupted across the country. Demonstrations blocked roads, banks were set on fire and at least 12 people were reported killed before an almost total internet blackout brought mobile data to a stop.

The internet was “almost completely shut down,” according to the New York-based Centre for Human Rights in Iran. “About 7% of [Iran’s] internet is accessible inside the country,” said Amir Rashidi, internet security and digital rights researcher.

His analysis found that authorities specifically targeted the messaging platforms WhatsApp, Viber and Instagram: “This is common practice among every single dictatorship,” Rashidi adds, “as soon as they cannot control a protest, they shut the internet down to stop people connecting to each other and the outside world.”

In the four months to November 2019, shutdowns have been used to suppress protesters in Sudan, Indonesia and Iraq. Between 2017 and 2018, the number of internet shutdowns almost doubled, according to research by digital rights group Access Now.

The worst repeat offender is a democracy

Notwithstanding the trend among authoritarian regimes, the most prominent offender since 2012 is also the world’s biggest democracy. India has shut down the internet more often than any other country.

Shutdowns in India have been targeted at specific regions - in the jargon, at "hyper-local" level. Authorities have sought to justify the shutdowns as a means to prevent or pacify protests sparked by the spread of fake news, which authorities blame for deaths caused by outbreaks of sporadic violence.

Critics dispute that argument, claiming the internet is a scapegoat for other failures. “Religious violence has always transpired in India, it’s not the internet that has created this,” says Aditi Chaturvedi, who works with India’s Software Freedom Law Centre. She has seen no evidence that shutdowns calm demonstrators. To the contrary, a study by researcher Jan Rydzak found that shutdowns in India actually exacerbate violence.

If shutdowns are not effective in calming protests, they may serve an ulterior motive. “The phenomenon we’re seeing is that shutdowns appear to be increasingly used to amplify the voices of authorities online,” says Alp Toker, executive director of NetBlocks, an organisation that tracks internet shutdowns.

In Iraq, where the internet has been disrupted since October, “we’ve seen the Iraqi government continue to use social media to publish alerts,” he says.

A similar pattern is evident in Iran. As most Iranians struggle to get online, the Tehran government has continued to use Twitter - banned in the country since 2009 - to broadcast its own version of events. According to the official narrative, the main beneficiaries of fuel subsidies were more affluent families, while the impact of rising fuel prices on other commodities would be “negligible”.

By exploiting internet shutdowns to amplify their own voices, and simultaneously suppressing all others, governments effectively turn social media into a “one-way medium,” warns Toker.

The trajectory of repression: who is responsible?

In 2011, a former CNN bureau chief in Beijing, Rebecca Mackinnon, published Consent of the Networked: The Worldwide Struggle For Internet Freedom. Her book challenged assumptions that the mere existence of the internet makes the world more free.

“I wrote a whole chapter about China being exhibit A, how an authoritarian regime adapts to the internet, using it to bolster its power,” Mackinnon told me. “Unless everyone - governments, companies and people - take responsibility for how the internet is governed and operated and used, the trajectory was going to take us in the direction of global networked authoritarians.”

So has Mackinnon’s vision of a “citizen-centric internet” been realised? “No,” she says, without hesitation. “People were delusional, companies were saying things like, because we exist, the world will be more free”.

While she believes the biggest tech companies should be more responsible, Mackinnon argues that it’s unfair to place the responsibility for internet governance solely at the feet of Silicon Valley.

The trajectory was going to take us in the direction of global networked authoritarians.

“The internet is an extension of human society. Power is going to get abused whenever anyone has power that can be abused without being checked in some way and we don’t really have the institutions or approaches when it comes to corporate or global governance to address these problems,” she says.

Now executive director of Ranking Digital Rights, an organisation that ranks the world’s most powerful internet players according to international human rights standards, McKinnon sounds pessimistic when we speak over WhatsApp.

“A lot of people think the internet is a problem that can be solved,” she tells me. “It’s not going to get solved, any more than - say - the city of London can become a perfect place for everyone who lives there. It’s going to be a constant negotiation between many inhabitants, and many different types of power.”

She insists that it’s not helpful to underestimate the challenge ahead: “I’m pretty optimistic for the long term - the next 100 years - but I think the next decade is going to be really tough.”

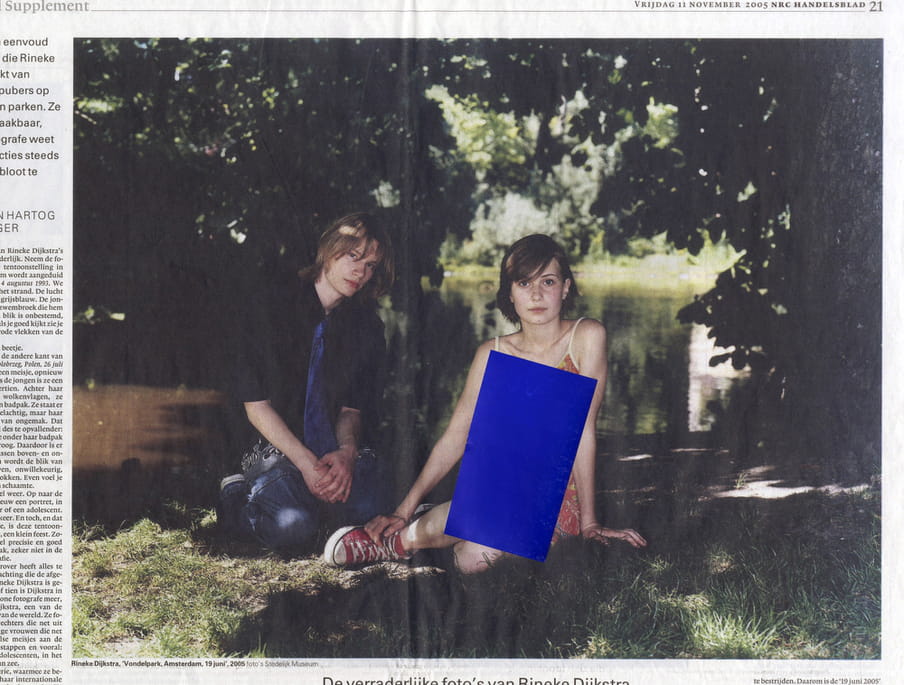

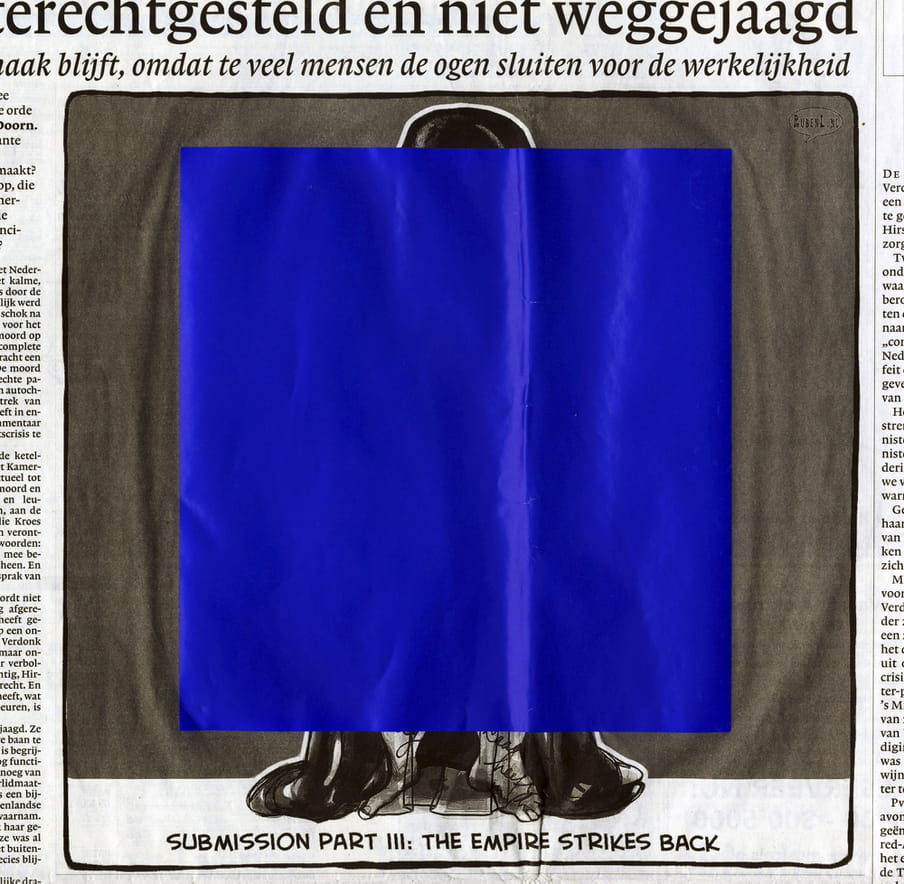

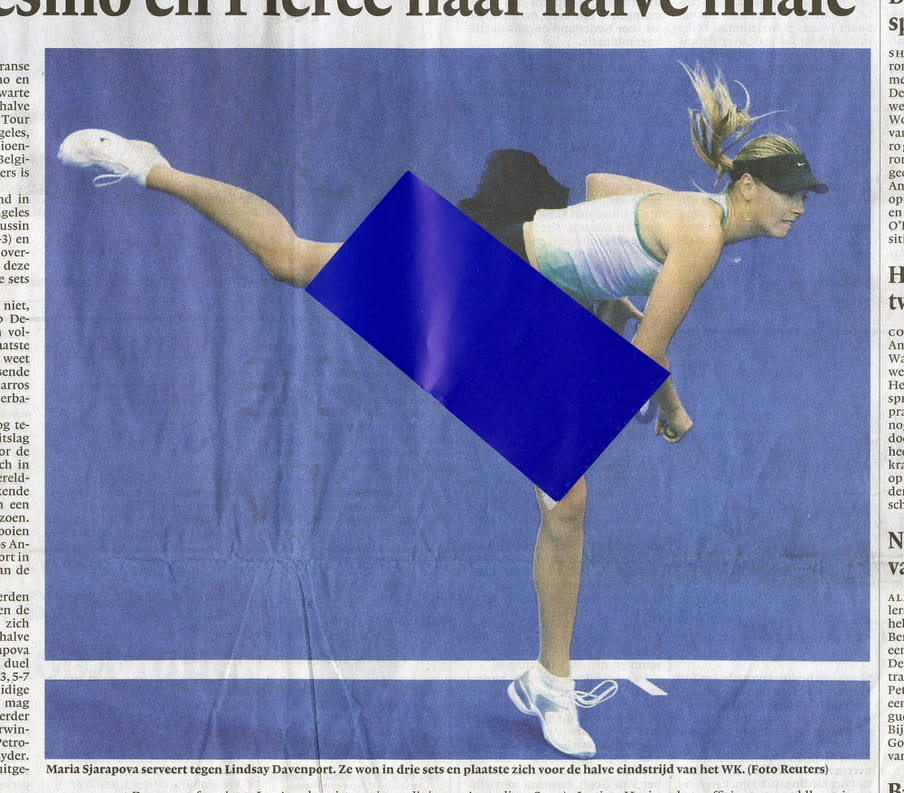

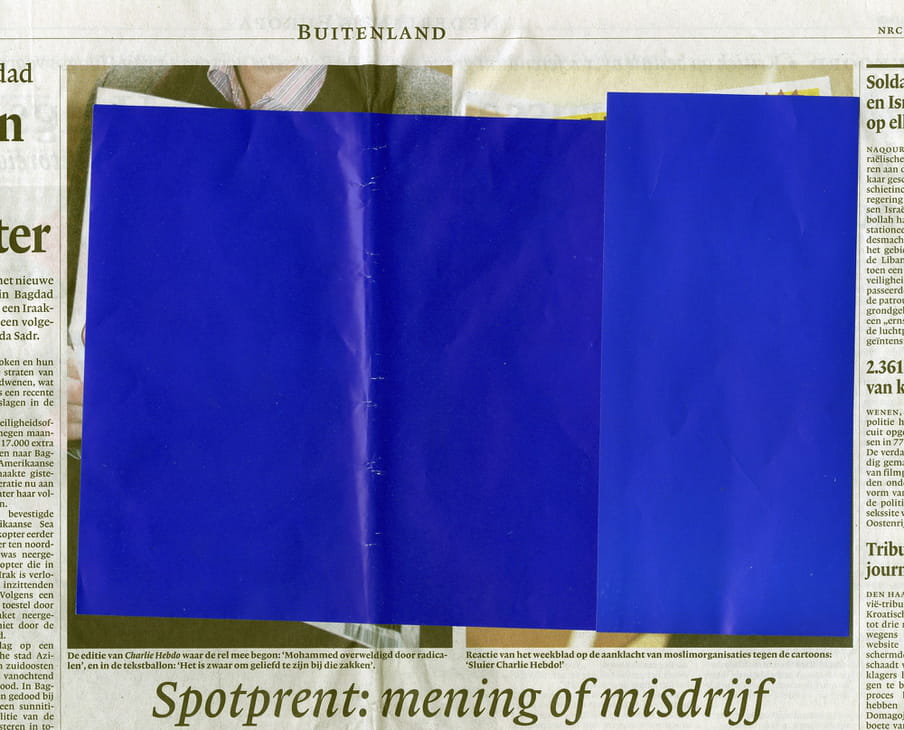

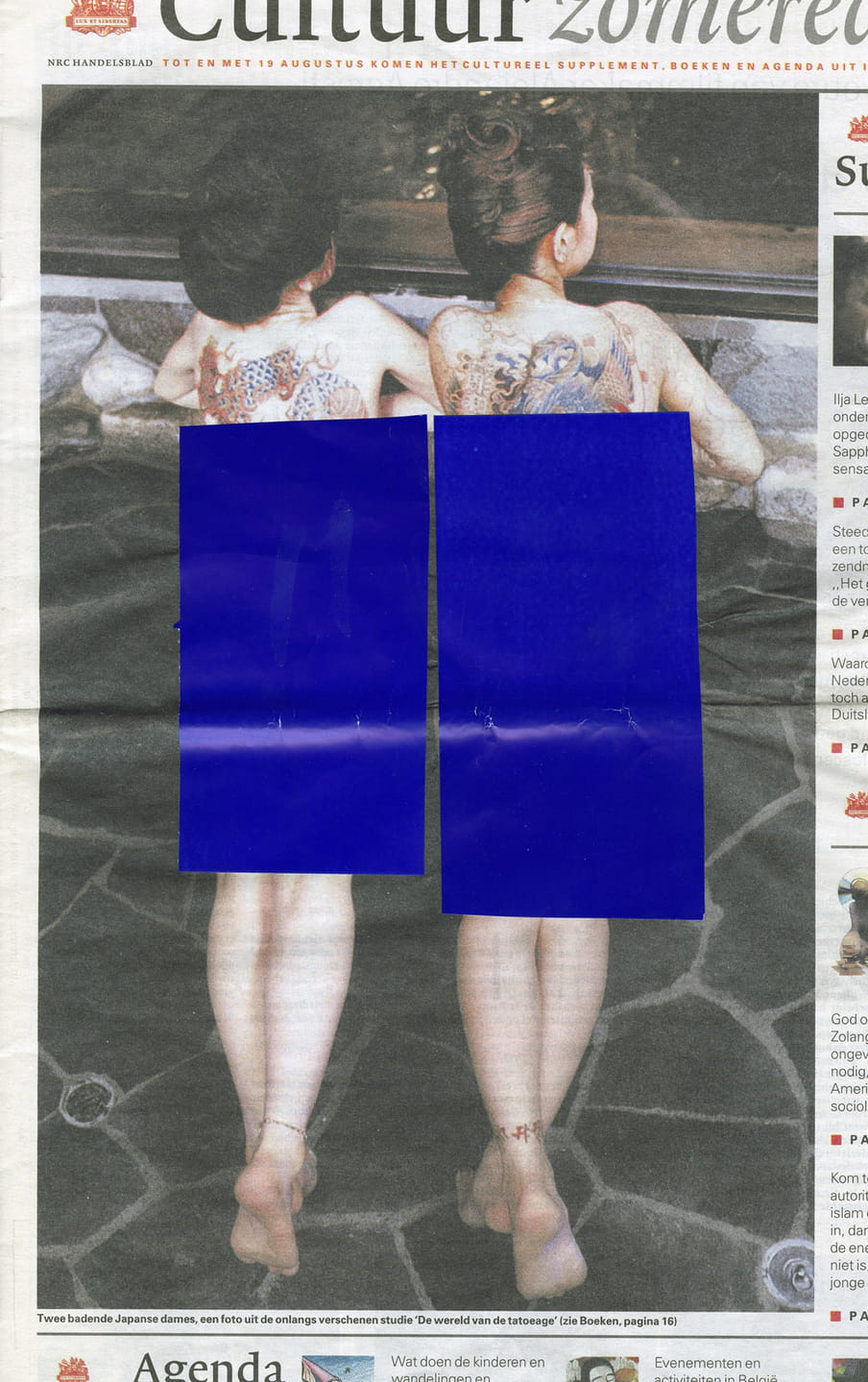

About the images

Every time Thomas Erdbrink’s copy of Dutch newspaper NRC Handelsblad landed on his doormat in Tehran, its contents had already been inspected. Iranian civil servants were tasked with opening the paper, and applying blue tape to cover up images that failed to meet the censor’s standards. Photographs were left intact as much as possible, with only the offending details obscured. The result fascinated and intrigued Dutch visual artist Jan Dirk van der Burg, a friend of Erdbrink’s, who dubbed the vetted paper The Censorship Daily. In 2012, he was crafting a book with this material when - out of the blue - the censorship stopped, without explanation. (Lise Straatsma, image editor)

About the images

Every time Thomas Erdbrink’s copy of Dutch newspaper NRC Handelsblad landed on his doormat in Tehran, its contents had already been inspected. Iranian civil servants were tasked with opening the paper, and applying blue tape to cover up images that failed to meet the censor’s standards. Photographs were left intact as much as possible, with only the offending details obscured. The result fascinated and intrigued Dutch visual artist Jan Dirk van der Burg, a friend of Erdbrink’s, who dubbed the vetted paper The Censorship Daily. In 2012, he was crafting a book with this material when - out of the blue - the censorship stopped, without explanation. (Lise Straatsma, image editor)