Hi,

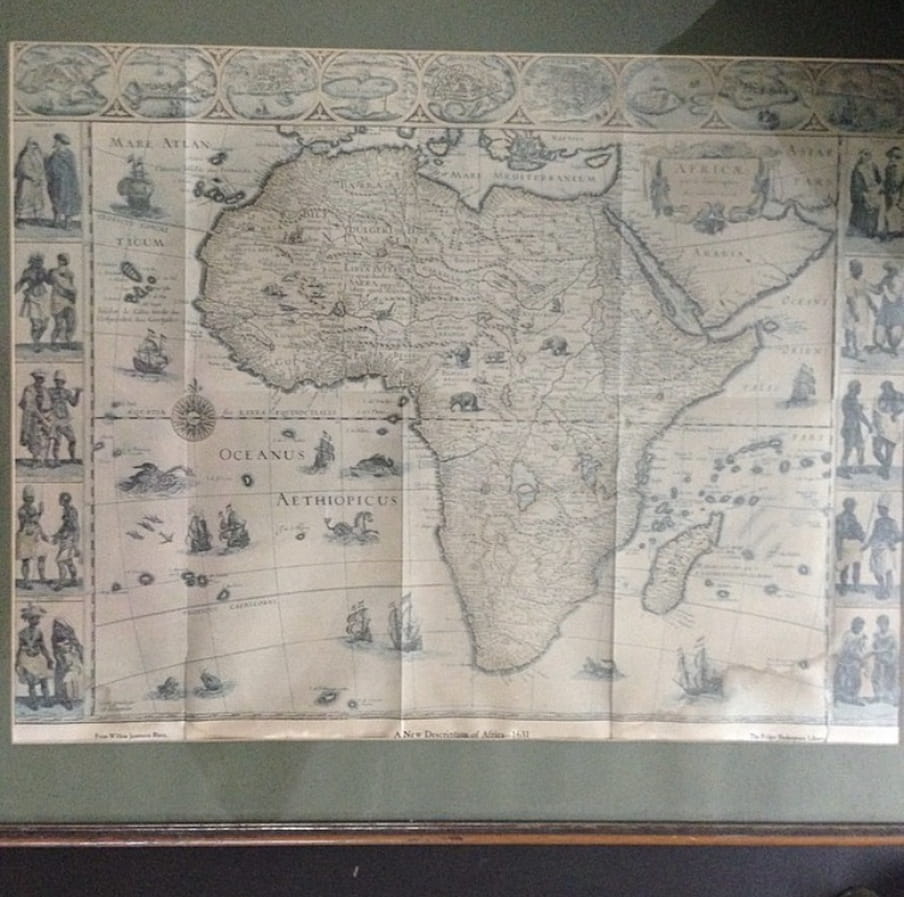

Four years ago, I happened upon a map with the words "A New Description of Africa". It was dated 1631, which made me wonder when the old description was published.

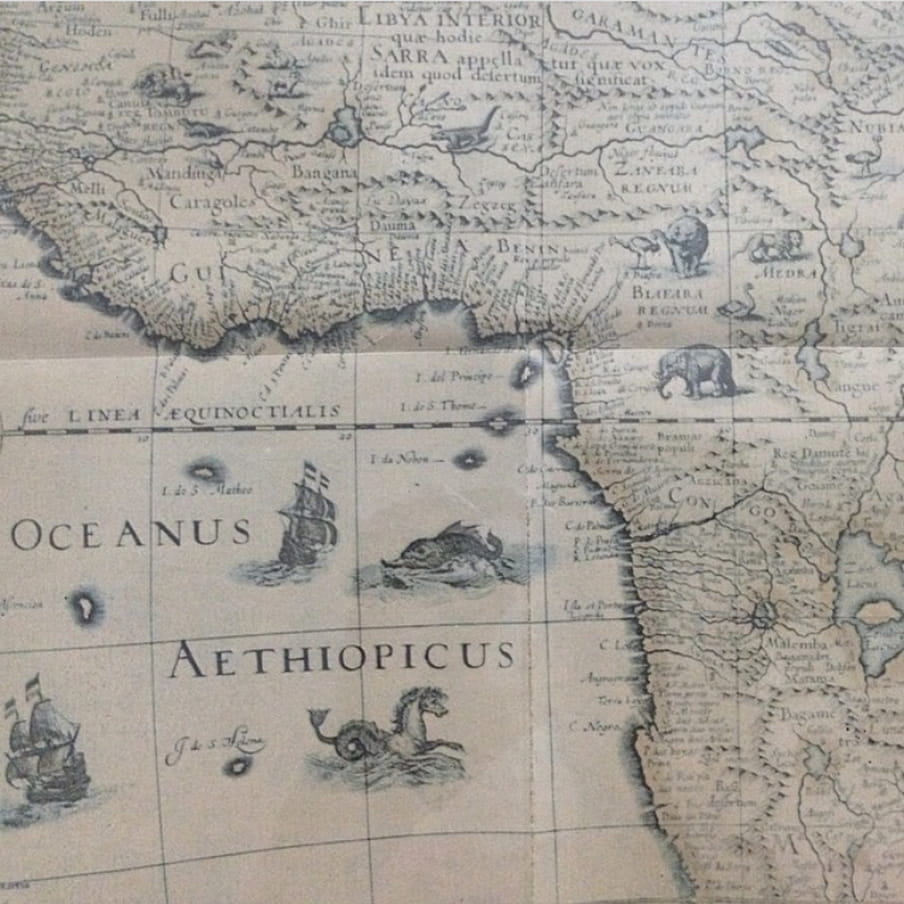

The only names I immediately recognised on this map were "Benin", which referred to the kingdom captured and destroyed by British forces in the late 19th century, Congo, and Libya. Needless to say, there were no borders or internal lines on this map, except those formed by the contours of the continent and natural formations such as rivers and mountains.

Today, a borderless world is considered by many to be a radical – and maybe even completely absurd – idea. Yet not that long ago, people would have found the idea of borders as we understand them in modern times just as absurd.

Having spent the last two or three weeks thinking intensely about borders and the violence that happens at some of them, I’ve come to the unsurprising conclusion that borders themselves are not the issue. It is the meaning that they are imbued with that determines whether or not they become sites of dehumanisation. When borders become symbols of the ideological barrier between citizens and an invading enemy horde, the inevitable consequence is suffering and death for many of those who seek to cross them.

In 1631 – and indeed, until 1914 – my country, Nigeria, did not exist. Today, as I move through the world, I inescapably carry my identity as a Nigerian with me. I have a passport, and a flag, and a national ID card, and an anthem. In theory, these symbols also mean that I feel some sort of special allegiance to the entity that is Nigeria. But less than 110 years ago, none of these things would have even been comprehensible to me.

I believe that borders, like any boundary which denotes social difference, can mean nothing more than a simple distinction between one and the other. After all, they don’t seem to be that good at their ostensible job: thwarting the desires of people who want to get out of or into a particular physical territory by any and all means. We don’t have to value borders more than we do human lives; we invented them. They should be subject to us, rather than us being subject to them.

As the conversation about open borders, free migration, and the rights of people to cross the earth at will rages on, I would like to remind us all that our world has been borderless far longer than it has not. And, no matter how many lines we draw on our maps, the planet itself will always be borderless. Just look at photos of the Earth and its continents from space.

Borders emerged out of the human need to categorise, claim, and conquer. We haven’t always had them, which I believe means we can definitely do without them. What do you think?

Want to receive my newsletter in your inbox?

Follow my weekly newsletter to receive notes, thoughts, and questions on the topic of Othering and our shared humanity.

Want to receive my newsletter in your inbox?

Follow my weekly newsletter to receive notes, thoughts, and questions on the topic of Othering and our shared humanity.