It started with a small idea.

We wanted to see what we could find out about the companies in the Netherlands that purport to make us safer.

But little ideas soon grow into big ones.

When we started to look into the subject, we discovered there was no “Dutch security industry” as such. Instead, Dutch security firms

- get their technology and expertise abroad,

- are often subsidiaries of international defense and technology giants,

- receive EU subsidies,

- operate on the international market, and

- are affected and influenced by events elsewhere, such as the recent attacks in Paris.

In short, security doesn’t stop at the border. It was time to take a transnational approach to the subject. We needed to map not the Dutch market but the European one.

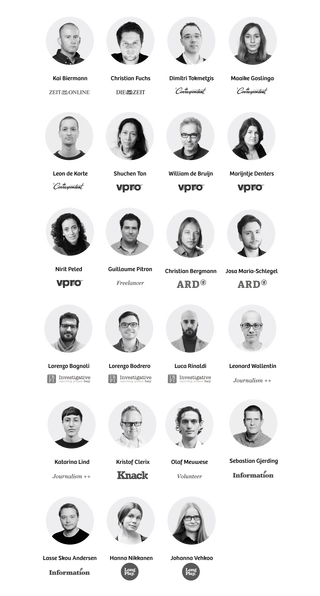

By mid-2016, we’d put together a solid consortium of 22 European reporters willing to help us do it.

How we got started

Let’s backtrack a little. In early 2016, we emailed journalists in a number of European countries with sizable security industries. We contacted some out of the blue; we were introduced to others by colleagues. We didn’t approach just anyone. We were specifically looking for our foreign counterparts – people as passionate about the subject of security as we were.

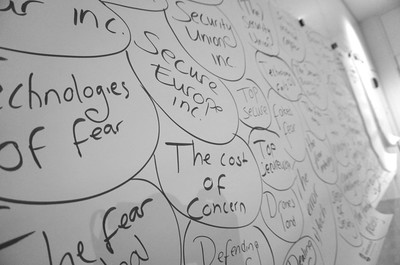

We briefly explained what we had in mind. Bodycams, drones, border surveillance, airport scanners, lawful interception, facial recognition – high-tech gadgets are being developed by businesses and deployed across Europe. But what kind of businesses make these technologies? How much money do they earn from them? How are they working with governments? And do these tools really make us safer? We wanted to find out. Not on our own, but working with a team from all over Europe.

Luckily, we didn’t have to do much persuading. Soon we had our team, made up of journalists from VPRO Tegenlicht in the Netherlands; Dagbladet Information in Denmark; ARD, Zeit Online and Die Zeit in Germany; Journalism++ and Svenska Dagbladet in Sweden; the Investigative Reporting Project Italy and l’Espresso in Italy; Le Monde diplomatique in France; and the Centre for Investigative Journalism in the UK.

But an idea is one thing. What should we do next?

We arranged to meet in Amsterdam on March 6 and 7, 2016. Sitting around a table with a big tray of croissants and thermoses of coffee, we embarked on a massive brainstorming session. Afterward, we divided up the tasks. For instance, we decided The Correspondent would concentrate on EU subsidies. The German reporters would focus on lobbying practices, particularly those engaged in by large German companies and influential individuals. And the Italian journalists would delve into border control.

These were the challenges

At ZEIT ONLINE in Berlin.

We met twice more, at an international journalism conference in Mechelen, Belgium, and at the Zeit Online offices in Berlin. Each time, we had new findings to report, and new partners too. Knack and Politico in Belgium joined the team. So did Long Play in Finland, and a filmmaker from Israel (working for VPRO Tegenlicht).

The past few weeks have been the most intense. How do you combine the research of 22 journalists into one unified whole?

It hasn’t been easy.

The consortium’s journalists come from TV shows, a magazine, newspapers, and our own online platform, The Correspondent. Each is focusing on a different aspect of the European security industry; all the aspects overlap with others in places. We’re writing in different languages. Every media outlet has its own text and picture editors with their own priorities, plus its own production schedule.

So fitting together the puzzle pieces of the various reporters’ research has been quite a job.

Here’s where we are now

But we’ve succeeding in respecting the wishes of every member organization, crafting relevant stories for each platform, and presenting them in the appropriate way. We’ve ended up with:

- big stories based on input from all the reporters;

- stories put together by one organization and reproduced by others, with additions where needed;

- stories put together by one organization and not published in other languages.

We’re collecting these stories on our project page Security for Sale. Over the next couple of months, we’ll be publishing more!

Why we believe this project matters

Collaborating with other journalists on this broad a scale is new for The Correspondent. Would we do it again – say, on the subject of the climate or another international issue?

Our answer is a resounding yes.

Of course, it will take plenty of time and effort. Chasing down colleagues is hard enough when they sit at the next desk, never mind a thousand miles away. Giving somebody a heads-up at the coffee machine is a lot faster than Skypeing them over a crappy connection. And the harsh truth is, cross-border productions cost money. Fortunately, our consortium received a grant from Journalismfund.eu, a Flemish foundation that promotes cross-border journalism. That money enabled us to fund travel and freelancers’ work.

We’ll undoubtedly do some things differently next time. For instance, The Correspondent now truly understands the importance of having a secure forum for document exchange. And on reflection, we’d like to have spent even more time researching the export of surveillance technology – a pressing issue about which EU legislation is currently being written.

Everyone at the meetings at ZEIT ONLINE in Berlin.

We believe international cooperation among journalists is absolutely necessary if we’re to understand and cover cross-border issues. Our research shows that security crosses borders by definition and must therefore be examined through an international lens. The same is true of money, the climate, and health. Journalists can only interpret the world and monitor power if we’re able to find patterns and look beyond national borders. And it’s our job to do those things.

But we can’t do it alone. In this group, we made full use of each other’s expertise. If you had a question, somebody else had the answer. And if you needed an interview with a faraway big cheese, a reporter on the ground would handle it. Exchanges of knowledge like these are vital, and they bring out the best in journalists.

In the end, we aren’t competitors. We make each other’s work stronger.

We want to express gratitude to our members, especially Olaf Meuwese and the 20 volunteers who helped build our surveillance database. You helped make this project possible. Thank you.

This piece is part of the investigative journalism project Security for Sale – reporting on Europe’s security industry in partnership with journalists from eleven European countries. Security for Sale is made possible by Journalismfund.eu

—Translated from Dutch by Laura Martz

More from Security for Sale:

Security for Sale. The price we pay to protect Europeans

The EU has deep pockets when it comes to security. But who reaps the benefits of generous subsidies? The public or the industry? For over a year now, we’ve worked with 22 journalists in 11 EU countries to investigate the European security industry. The result is Security for Sale, which brings you up to speed on this burgeoning sector.

Security for Sale. The price we pay to protect Europeans

The EU has deep pockets when it comes to security. But who reaps the benefits of generous subsidies? The public or the industry? For over a year now, we’ve worked with 22 journalists in 11 EU countries to investigate the European security industry. The result is Security for Sale, which brings you up to speed on this burgeoning sector.

How European spy technology falls into the wrong hands

Since 2014, the EU has tried to put a stop to the sale of surveillance technology to undemocratic nations. But goods and expertise are still being exported to authoritarian states, our international consortium Security for Sale found.

How European spy technology falls into the wrong hands

Since 2014, the EU has tried to put a stop to the sale of surveillance technology to undemocratic nations. But goods and expertise are still being exported to authoritarian states, our international consortium Security for Sale found.

The surveillance industry still sells to repressive regimes. Here’s what Europe can do about it

The European Union has tried in vain to stop the export of spying technology to despotic states. Why is the industry so hard to regulate? Here’s our analysis.

The surveillance industry still sells to repressive regimes. Here’s what Europe can do about it

The European Union has tried in vain to stop the export of spying technology to despotic states. Why is the industry so hard to regulate? Here’s our analysis.