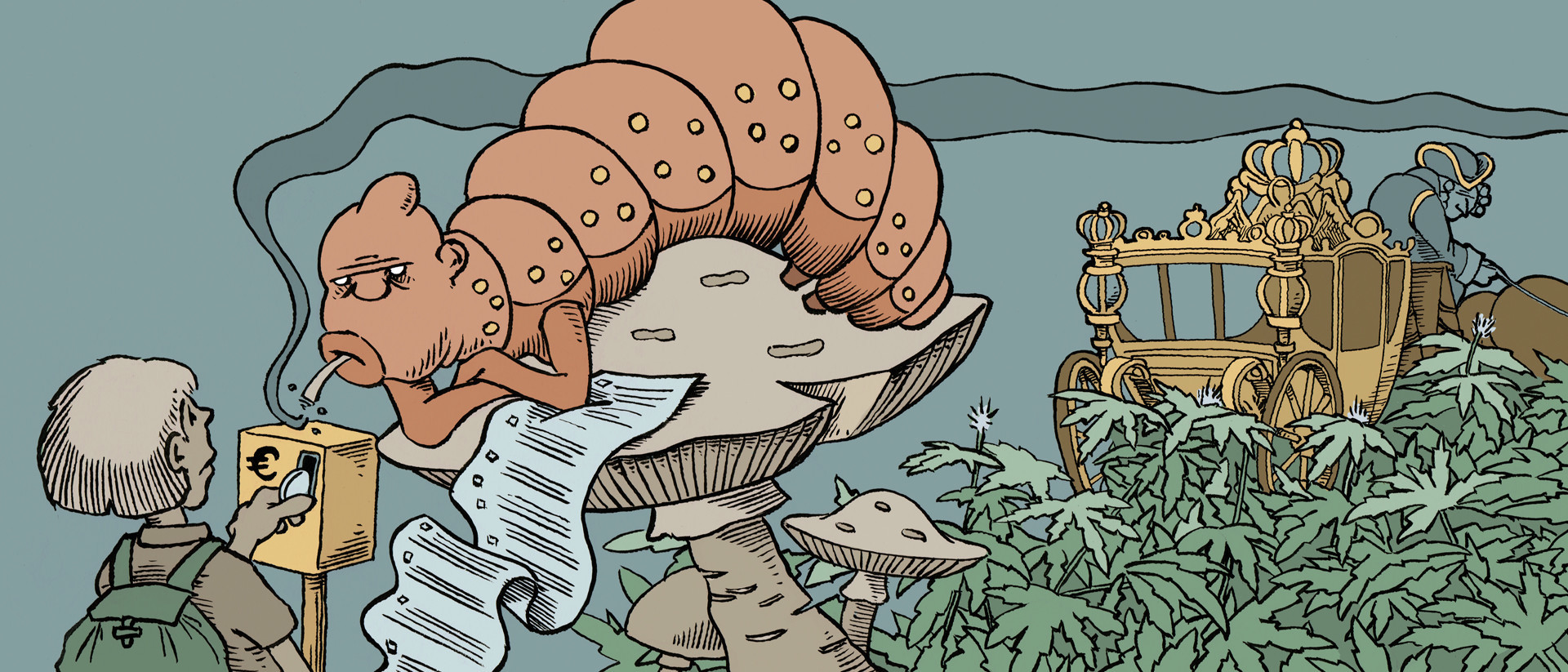

Effective civics classes help refugees integrate into Dutch society as quickly as possible. And that’s what newcomers to the Netherlands hope for once they get their residence permits.

Yet only about half of refugees report being “satisfied” or “very satisfied” with the mandatory civics course they’re attending. About 20% is just plain “dissatisfied”. Our survey confirms what a growing number of refugees, researchers, and municipalities are saying: the civic integration policy doesn’t work.

Source: Interviews conducted by our members

The numbers above refer to the 172 newcomers taking part in the New to the Netherlands initiative. They recently completed a third questionnaire together with a Correspondent member. The results are not representative; they are a starting point for journalistic research.

Civics classes for newcomers: a good idea, poorly executed

Required civics courses are intended to help promote the integration of newly-arrived refugees into Dutch society. In order to build new lives for themselves, refugees will need to learn to speak and write in Dutch. It’s also useful to know how Dutch society works, and how the country’s job market operates. Civics classes for newcomers are intended to help with all of that.

In practice, however, those goals are being insufficiently realized, or only very slowly. The quality of civics education can vary widely and enforcement of standards is lax – this much is clear from the results of our survey among New to the Netherlands participants. A report commissioned by the Dutch Ministry of Social Affairs supports that conclusion as well. Godfried Engbersen of the Scientific Council for Government Policy confirmed this in an exchange with contributing correspondent Colette van Nunen.

Before we delve any further into the results of our survey, it might be useful to lay out the basics of Dutch civic integration policy.

Since 2007, all foreign nationals from non-EU countries who wish to settle in the Netherlands are required by law to take part in an integration process, except those under 18 or over 65 years of age. This applies to all refugees who are granted a residence permit.

Members of this group have three years to pass their civic integration exam. Shortly after being issued a Dutch social security number, they receive a letter from the Education Executive Agency that contains the start date for their term of integration. As of October 1, 2016, a total of 80,000 people were subject to the civic integration requirement.

There are two ways to meet this requirement: by passing the civic integration exam or by passing the state examination for Dutch as a second language, the NT2 exam, plus one or two additional exams. Most refugees set their sights on the civic integration exam. For the vast majority of people who were issued a residence permit after 2014, this means that they must pass six exam components within three years’ time, one of which includes four Dutch-language tests: reading, listening, writing and oral skills. There are also exams on “knowledge of Dutch society” and “Dutch job market orientation”.

Privatized courses: you’re on your own, newcomers

The Dutch Civic Integration Act has changed drastically since 2013. Civic integration has been privatized. Until 2013, local authorities were responsible for integration policy. They provided the classes and monitored the progress of participants. Civic integration was seen as one of the duties of a properly-functioning pluralist society, a society that seeks to ensure economic independence and opportunities for self-improvement while working to prevent segregation.

Source: Interviews conducted by our members

As of 2013, however, immigrants have been obliged to bear responsibility for their own civic integration. They must somehow manage to make a well-informed, considered choice from among a disorderly array of privately-owned businesses offering civic integration courses, usually at a point in time when they have only just been assigned to a particular city. “Are you looking for someone to help you get started with civic integration?” asks the government website inburgeren.nl. The answer is telling. “Maybe your family can help. Or a friend.”

In the last few years, more and more businesses have rushed headlong into the lucrative civic integration sector. Refugees now have their choice of 190 businesses that have been certified by the quality assurance institute Blik op Werk. This quality seal indicates that lesson providers have a proper curriculum and enough qualified teachers. But the institute doesn’t have guidelines in place for class size or number of teaching hours, nor for measuring whether a business offers classes that differentiate between existing knowledge levels.

The survey among New to the Netherlands participants showed that some 65% needed help in choosing a class. Only about 50%, however, actually received assistance from VluchtelingenWerk or another aid organization. Some 70% reported that the support was sufficient to allow them to make a well-considered choice.

In choosing a class, most of those asked felt the level of the course was the most important consideration, followed by the distance between their home and the lessons. The cost of the class played only a marginal role. That makes it easy for businesses to charge fees that bear no relation to the quality of education. It also begs the question of whether newcomers are aware of the financial repercussions of their decision.

Integration is more expensive than you think

Civic integration costs a lot of money. The journalistic research of New to the Netherlands reveals that, for at least 60% of respondents, the civic integration course cost more than 1,000 euros each quarter, which is over 4,000 euros a year; for approximately 40%, the quarterly cost exceeds 1,250 euros, which is more than 5,000 euros a year.

Source: Interviews conducted by our members

Newly-arrived immigrants can borrow up to 10,000 euros from the Education Executive Agency (the DUO) to pay for their civic integration. Refugees with a residence permit who have applied for asylum in the Netherlands do not have to repay this loan if they pass the exam within three years. If they don’t, they will have a significant amount of debt – and be fined on top of that. It gets worse: their welfare benefits may be docked and their residence permit could be revoked.

The partners, parents, and children of asylum-seekers also qualify for loans to pay for their civic integration education. They, too, are exempt from repayment so long as they pass the exam within the three-year term. Should they fail to do so, they face the same sanctions as the other refugees.

As of 1 October 2016, the outstanding loans issued by the DUO for civic integration totalled 132 million euros. That number represents the civic integration industry’s turnover since its privatization: 132 million euros.

Yet classes are below par

So, are refugees getting their money’s worth? Some 65% attend classes with twelve or more students, and 30% are in groups of sixteen or more. Individual levels within a class often vary widely.

Around three-quarters of New to the Netherlands participants attend class fewer than twelve hours a week, and some 40% have fewer than nine hours of class each week. And this is supposed to prepare them for six exam components. In a “school year” lasting forty weeks, civic integration can then easily take one and a half to two years, despite the fact that many newcomers are in a big hurry to start new lives here. All things considered, over half of those who filled out the questionnaire report being “satisfied” or “very satisfied”. About 20% are “dissatisfied”.

Source: Interviews conducted by our members

Dozens of respondents explicitly state they are not getting their money’s worth from the courses. A selection of comments:

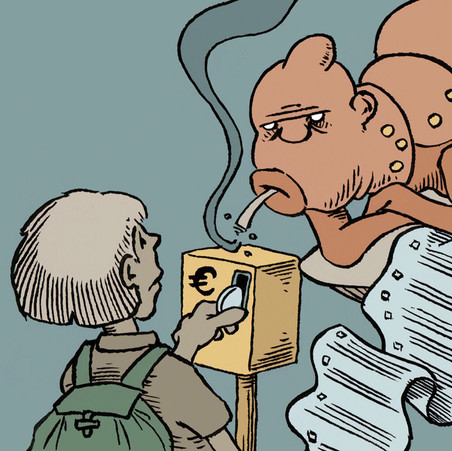

- “A lot of times, the language providers seem like stores to me; the education itself doesn’t seem to be the top priority.”

- “They’re only out to make money, it’s not about helping anybody learn.”

- “I’m dissatisfied with the people teaching the class. They’re always glancing at the clock and don’t really seem interested in their students. Very commercial.” And:

- “My school is mostly concerned with wheedling money out of folks.”

- One person said they got the “strong impression that education providers are ripping off the state.”

And the most commonly-heard complaint? The measly number of teaching hours. Other gripes included: too few qualified teachers; that they moved through the lesson material too slowly; that the difference in individual levels within a single class is too great, so that the weakest student determined the overall level; and that students don’t get enough time in class to practice conversational skills.

All of that’s in line with the results of a study conducted by EenVandaag last September. Many refugees complained about not having enough hours in class, that the education was substandard and that it lacked a connection to society. In addition, four of the five largest cities in the Netherlands voiced dissatisfaction with the way civic integration in the country is being managed.

The current policy doesn’t work

The current civic integration policy doesn’t work. In the interval since the Civic Integration Act turned responsibility for implementation over to newcomers and free-market forces, participation in civic integration courses has declined – just like the percentage of newcomers who pass the exam within three years.

Lodewijk Asscher, the Dutch Minister of Social Affairs, is well aware of this. As early as last April, he called the results ‘troubling.’ “We’re hearing accounts of unqualified individuals dabbling in the language sector,” he said at a conference. “While these reports are anecdotal, they say that agencies are luring people to sign up for courses with special perks like laptops. And other businesses are out to grub as much money as they can, instead of helping people pass their exams as quickly as possible.”

Asscher presented the latest figures in October. Of the very first group of new immigrants who – in the first quarter of 2013 – were given three years to complete civic integration, 49% have been successful. Of the rest, one group was still actively working towards completing integration and had a valid reason for failing to comply with the time limit for the process.

In a letter to the Dutch House of Representatives, the Minister acknowledged that current civic integration policy is ineffective. “When this free-market system was introduced, our expectation was that market forces would result in more individually-tailored solutions... We now see, however, that realizing this intention has proven difficult.”

Asscher also admitted that “for the people required to complete civic integration, there is insufficient insight into the quality of the courses available.” He announced plans to tighten supervision, among other measures. When the revised Civic Integration Act goes into effect on July 1 of this year, local authorities will once again have better control and oversight over the civic integration process. The goal is to allow “this new system of civic integration to function effectively as soon as possible.”

Effective on July 1, refugees with a residence permit must meet an additional requirement: they will be required to sign a “participation declaration” that states they are familiar with Dutch values and that they promise to respect these values. Some 70% of New to the Netherlands participants feels that is a “good” or “very good” idea.

Outside of class, newcomers speak very little Dutch

Something the civic integration policy fails to take into sufficient account is that many newcomers are speaking very little Dutch outside of class. This is apparent from the results of our New to the Netherlands survey. Some 70% of respondents have a language buddy or coach, or a Dutch person who’s willing to spend at least a half-hour each week with them, for conversational practice.

Source: Interviews conducted by our members

Some newcomers are really lucky: about 35% spends more than two hours a week outside of class speaking Dutch. On the other hand, around a quarter of those interviewed get less than a half-hour of practice each week. And that’s despite the fact that most refugees are eager for more contact with Dutch people, as an earlier questionnaire from New to the Netherlands revealed.

Source: Interviews conducted by our members

Illustrations by Hans Klaverdijk

One participant in the initiative spoke of wasted opportunities: “We never have contact with anyone outside of our own classroom and our own classmates – not even with the Dutch students that go to the same school we do, like at a party, for example. That’s a terrible waste of an opportunity for integration. Another wasted chance is that we’re never taught outside the classroom; they could take us shopping, for instance. It’s absolutely not enough to just sit in a classroom the whole time, isolated from Dutch people.”

Civic integration is a lengthy process that doesn’t stop once you’ve passed your exam, Godfried Engbersen of the Scientific Council for Government Policy told contributing correspondent Colette van Nunen. “Becoming a citizen is a complicated undertaking.” It can only succeed when both newcomers and society do their very best, and when the government supports these efforts.

This report is part of the New to the Netherlands initiative, which is made possible by support from the Dioraphte Foundation.

—Translated from Dutch by Liz Gorin and Erica Moore

More from De Correspondent:

How theater helped 22 Syrian refugees find their way in a new land

Community theater as a means to integration – it’s never been seen before in this country. One Dutch town has put the idea to the test, and I went to have a look. Language skills improved, prejudices disappeared, and new contacts were made. “All of us are truly happy about this.”

How theater helped 22 Syrian refugees find their way in a new land

Community theater as a means to integration – it’s never been seen before in this country. One Dutch town has put the idea to the test, and I went to have a look. Language skills improved, prejudices disappeared, and new contacts were made. “All of us are truly happy about this.”

Refugees on their struggle to look ahead while worrying about those left behind

Bound to their homeland. Fearing for friends and family. Being this close to family reunification. Three insights into how things are going for refugees with a residence permit in the Netherlands.

Refugees on their struggle to look ahead while worrying about those left behind

Bound to their homeland. Fearing for friends and family. Being this close to family reunification. Three insights into how things are going for refugees with a residence permit in the Netherlands.