On October 9, Donald Trump debated Hillary Clinton twelve miles away from what he has deemed one of the most dangerous places in the world: Ferguson, Missouri. One would think there is some tough competition for this title – Syria comes to mind – but no, it is Ferguson that Donald Trump fears. Since 2014, Trump has repeatedly claimed Ferguson is overrun with roving gangs of illegal immigrants. “Rough dudes,” he warned, and assured America that if elected, he would evict them.

Ridding Ferguson of illegal immigrants shouldn’t be too hard: the foreign-born population of Ferguson is 1.1%. Cracking down on illegal immigrant gangs should be even easier: there are none.

The Ferguson that Donald Trump describes exists only in his imagination. To be fair, he is not alone in portraying Ferguson inaccurately: countless media outlets proclaimed the mundane lower-class suburb a “ghetto” or a “war zone” in 2014, after police brutally suppressed protesters grieving the death of Michael Brown, the 18-year-old shot dead by police officer Darren Wilson.

But Trump is unique in ascribing Ferguson’s woes to roving bands of illegal immigrants.

While Ferguson remains deeply divided, there is one issue that all citizens in Ferguson – black or white, protester or policeman – can agree on: Donald Trump knows nothing about their town. What is it about Ferguson, they wonder, that fills Trump with such fear? The farmer’s market? The new Starbucks? The strip malls and pie shops?

Trump has toured the country, yet learned nothing

The bafflement expressed by Ferguson residents is not unique. Throughout the election, Trump has behaved as a stranger in his own land even as he tours it. He talks like a time-traveler wearing a blindfold, living in 2016 but mentally trapped in the early 1980s. He could stay locked in Trump Tower, listening solely to the rap lyrics of Grandmaster Flash and the heartland rock of John Mellencamp, and emerge with the same views of rural and urban life as he does after more than a year on the road.

It would be funny, if he weren’t running for president.

Trump is known for pointed and malicious lies – spurious claims of rigged elections, audacious denials of statements he made and things he did, vicious stereotypes of ethnic and religious groups, and libelous attacks on individuals. His portrayals of U.S. cities (and the suburbs like Ferguson he mistakes for cities, having never visited) seem different, rooted as they are in ignorance and indifference. But the end result is just as insidious.

Trump’s comments on cities are among the clearest evidence yet that Trump has little respect for actual inhabitants of actual places. So little, he does not worry they will counter him with facts about their own hometowns, or be offended by his gross inaccuracies. They are merely bit players in a fantasy America starring Donald Trump. These urban dwellers appear in his speeches over and over – not as human beings with whom he has engaged, but as caricatures in a dated tragedy.

Photos by Jewel Samad / AFP

This fantasy America reveals the depth of Trump’s contempt

“I want to do things that haven’t been done, including fixing and making our inner cities better for the African-American citizens that are so great, and for the Latinos, Hispanics, and I look forward to doing it. It’s called make America great again,” Trump proclaimed at the St. Louis debate. There are many strange things about this statement – the use of “the” before ethnic groups, for example, as if they are remote monoliths – but his portrayal of urban America itself is insulting and flawed.

Let’s begin with St. Louis, the site of the second debate, and the city I know best, because I live here. Prior to his October arrival, Trump had visited St. Louis twice during his campaign: once in March, at a rally at the Peabody Opera House in downtown St. Louis, and once for the September funeral of Phyllis Schlafly, an American conservative icon and St. Louis resident. Unlike Hillary Clinton, who met with black St. Louis citizens in the city during the primary season, Trump made no effort to venture into non-white St. Louis neighborhoods to meet with “the African-Americans” or “the Latinos, Hispanics” he keeps bringing up in his speeches.

Granted, had he done so, it may not have gone well. The St. Louis Trump rally was the first one to be seriously disrupted by protesters, which consisted of an incredibly diverse array of St. Louisans – black, Latino, Muslim, LGBT, Jewish, white, young, elderly – uniting in a demonstration against Trump’s hatefulness and bigotry.

When not treating black Americans as if they are pitiable and interchangeable, Trump treats them as a hostile force

But one would think Trump would have some interest in at least exploiting St. Louis for his own purposes, as St. Louis is one of the very few cities that – in a few respects – fits his stereotype of what an “inner city” is. Before touching on what, in his perverse and unintentional way, Trump gets right about “inner cities”, let’s examine the many things he gets wrong.

At the debate, Trump was asked by a man from the St. Louis region, James Carter, whether he would be “a devoted president to all the people in the United States”. Because Carter is black, Trump immediately resorted to stereotypes:

“I would be a president for all of the people, African-Americans, the inner cities. Devastating what’s happening to our inner cities…. You go into the inner cities and – you see it’s 45% poverty. African-Americans now 45% poverty in the inner cities. The education is a disaster. Jobs are essentially nonexistent.”

In Trump’s worldview, there are no middle or upper-class black citizens, only a horde of jobless, uneducated Americans fighting for survival amidst the urban blight. This is an inaccurate and insulting portrayal of black American life, one that completely neglects diversity of income, education, profession, and residency. And when not treating black Americans as if they are pitiable and interchangeable, Trump treats them as a hostile force – as he did most notably with the Central Park Five, the black teenagers falsely accused of rape in the 1980s and jailed thanks to Trump’s persecution.

Photos by Sarah Rice / Getty Images

Not a word about the suburbs, which are struggling...

Then there is his contention that poverty exists in two places: impoverished majority white small towns, where his followers live, and dangerous “inner cities”. Suburbs do not fit into this equation, but suburbs – both diverse and impoverished – are where the crisis of American poverty has spread.

Ferguson, and the surrounding suburbs of St. Louis’s North County, are a prime example of the transformation of the American suburb. Once primarily white and populated by blue-collar workers, North County is now heavily black and populated with service workers, a result of the erosion of the economy, black flight from St. Louis city as families fled to the suburbs for a better quality of life, and white flight from North County as racists fled black people. The arrival of black families in the suburbs prompted white North County residents to move to distant, majority white exurbs. Not coincidentally, these exurbs are where the Trump campaign headquarters are now located.

St. Louis is not unique in its rise of suburban poverty – the same phenomenon is occurring across the U.S., as inner cities become gentrified, driving out lower-income residents who can no longer afford to call them home. These cities are often lauded as “success stories” – Trump’s hometown of New York is a prime example – but the end result is often a literal white-washing, in which wealthy white newcomers are given the resources non-white residents were long denied to “clean neighborhoods up”. The original inhabitants rarely benefit from the new businesses that move in (as those businesses tend not to hire locals), but instead suffer soaring rent and denigrating attacks on their communities as a consequence.

Suburbs do not fit into this equation, but suburbs – both diverse and impoverished – are where the crisis of American poverty has spread

Furthermore, the problems of poverty, underemployment, and racial discrimination that former inner city residents often experience do not go away when they are priced out of the neighborhood. Those problems remain with them in their new location – nowadays, the cheaper suburbs – only now basic advantages of city life like public transportation and access to a variety of jobs are gone.

But there are some neighborhoods in “inner cities” that actually do resemble Trump’s broad caricature, like here, in St. Louis. The city has been a prime relocation site for refugees for over a century – thanks in part to its low cost of living and long-standing local organizations aimed at providing for refugee communities – and I have lost track of the times a refugee tells me parts of St. Louis look worse from where they came, cities including 1990s-era Mogadishu and Sarajevo.

While some mundane suburban towns, like Ferguson, are falsely described as resembling war zones, there are other areas of St. Louis where this description is fairly accurate. Collapsed and burnt-down buildings line the streets, shrines to homicide victims dot the corners, infant mortality is high, schools are closed, shootings are frequent, and unemployment is rampant. These neighborhoods are almost always majority black, their problems have continued for decades, and they are unlikely to be remedied quickly. They actually resemble the blighted urban landscape described by Donald Trump. Of course Trump has shown no interest in understanding what problems citizens in these neighborhoods face, how they cope, or what they want. To be fair, the Democrats rarely have either, from what residents tell me.

Photos by Brian Blanco / Getty Images

...while locals roll up their sleeves.

But that doesn’t mean no one’s doing anything. What you’re most likely to find in inner cities are citizens, with extremely limited resources and zero acclaim, trying to fix the communities themselves.

The most common sign you see in these St. Louis neighborhoods is not for a presidential candidate, but a sign that proclaims “We Must Stop Killing Each Other.” The signs were distributed by a local black church organization, and proved wildly popular with those appalled by violence. Some residents are skeptical of the signs, seeing them as a superficial way to address structural problems like racism and police brutality, but others have embraced them as a public moral condemnation.

Trump is not going to fix inner cities. He has proposed no policy for them except the racist “stop and frisk”

All over these neighborhoods, you will find acts of kindness and protectiveness – some grand, many small, most rarely covered in the news. I have seen young black men who would be stereotyped by Trump as dangerous go out of their way to assist elderly black residents in need. I’ve met black writers and artists and rappers who want nothing more than to get the story of their neighborhood out, so that fellow residents will receive more resources and support. I have visited an after-school center set up by an ex-felon to provide safe and fun activities for local children. He told me many of the attendees are children of drug dealers, who hope the center will deter kids from following the path they resorted to out of financial desperation. And I have also witnessed muggings, and heard gunfire, and seen drug deals, because that is part of life there too.

Trump is not going to fix inner cities. He has proposed no policy for them except the racist “stop and frisk”. He has had every opportunity over his long, privileged life to take interest in these areas, and he has shown none. At the same time, the Democrats who tend to represent these areas, while at least having a more realistic assessment of what neighborhood life is like, have often been ineffective in their legislation.

Give locals the resources, and they’ll get the job done

The most likely people to fix blighted inner cities are residents of blighted inner cities. What they need is money, resources, and trust from officials that residents know their neighborhoods’ problems best and therefore may have the best solutions to fix them. This level of trust is rarely extended due to a focus on formal education and credentials, which people who grow up extremely poor cannot afford to attain. But formal outside validation is meaningless in these areas, and often locks intelligent and compassionate people out of opportunities to help others, since they cannot apply for grants or jobs to do so. Often the biggest concern is simply surviving, and helping others survive.

It is shameful that Trump has brought up inner cities in the way he does – carelessly, impersonally, and, if strategically at all, aimed at confirming stereotypes his white followers share. While not as overtly adversarial as his attacks on Muslims, Mexicans and other religious or ethnic groups, Trump’s descriptions of inner city life are just as dehumanizing. In his vision, inner city blacks are not players but pawns. When asked why black voters should back him, his response is a dismissive “What do you have to lose?”, as he simultaneously advocates destructive policies like racial profiling.

There is always more to lose: the St. Louis neighborhoods that have declined for decades are proof of that. There is also the possibility to turn things around. But for that to happen, residents of inner cities need material support and public respect – not the sneering bromides of Donald Trump.

More stories from The Correspondent:

Meet Darren Seals. Then tell me black death is not a business

This Ferguson protestor and local activist was found murdered in St. Louis last month. To the end, Darren Seals continued to call out those who exploited black suffering for their own benefit – something that didn’t always win him friends. A portrait of a city’s pain and a life cut short.

Meet Darren Seals. Then tell me black death is not a business

This Ferguson protestor and local activist was found murdered in St. Louis last month. To the end, Darren Seals continued to call out those who exploited black suffering for their own benefit – something that didn’t always win him friends. A portrait of a city’s pain and a life cut short.

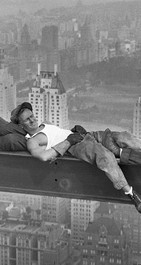

How nostalgia blinds Trump to the reality of working class America

The American middle class has been shrinking for decades. It’s one reason for the success of Donald Trump’s presidential campaign, in which he claims to represent American workers. But the irony is that Trump has no idea who today’s workers are or what kind of work they do.

How nostalgia blinds Trump to the reality of working class America

The American middle class has been shrinking for decades. It’s one reason for the success of Donald Trump’s presidential campaign, in which he claims to represent American workers. But the irony is that Trump has no idea who today’s workers are or what kind of work they do.

How I tried to cover 605 elections in one day

This election year, instead of following the Big Race, I’ve been talking to everyday Americans campaigning to improve their cities and streets. In April, I set out to cover 605 local races and proposition votes in one day – which turned out to be a big race in itself.

How I tried to cover 605 elections in one day

This election year, instead of following the Big Race, I’ve been talking to everyday Americans campaigning to improve their cities and streets. In April, I set out to cover 605 local races and proposition votes in one day – which turned out to be a big race in itself.