What role might the courts play in addressing the problem of climate change? This is no longer a rhetorical question: next week, a Dutch judge will issue a ruling in a case brought by the action organization Urgenda against the Dutch government, charging that it has not done enough to prevent dangerous climate change. But more on that in a moment.

Our story starts in the early 1990s in the Philippines. Antonio Oposa, lawyer and environmental activist, had a brilliant idea that would go on to have far-reaching consequences.

He wanted to put an end to industrial logging in his country. In just under 100 years, 90% of old-growth forest in the Philippines has been chopped down, making a tiny elite billions of dollars richer, costing millions of people their homes, and seriously undermining the country’s ecological resilience. The archipelago once described by a Spanish poet as the “Perla del mar de Oriente” was losing its luster.

“What if I were to ask a judge to issue an opinion about this?” Oposa thought. “What if I could prove that something we believe to be unjust is in fact illegal?”

Oposa wanted to prove that in issuing lumber permits, the government was facilitating the depletion of natural resources and thus victimizing future generations. Their rights to a balanced and healthful living environment were being violated.

Who better to argue that fact than the future generations themselves? Oposa asked his friends and family if he could take legal action on their children’s behalf. He eventually filed a class action suit on behalf of 43 children and their parents, as well as all Philippine children yet to be born.

The first judge declared that minors (living and unborn) lacked the legal standing to sue and that the complaint was not specific enough. But Oposa appealed the ruling – all the way up to the Supreme Court of the Philippines, where something astonishing happened.

The court ruled in the children’s favor on all counts.

Deforestation in the Amazon, Brazil. Photo by Ricardo Funari/Getty Images

Each generation is responsible for the next

The concessions the government had granted the loggers were deemed unlawful because in essence they granted it permission to deprive succeeding generations of a healthy living environment. Politicians do not have the right to disrupt nature to such an extent that it will not support future generations – even if the demands of “economic development” dictated that they use up all of the natural resources in a single generation.

The Philippine judge took it a step further, moreover. He reminded the government of the Philippines of its constitutional duty to, in fact, promote a healthy living environment.

The idea that each generation is responsible for preserving the environment for succeeding generations, that children can go to court in the name of their own and future generations to protect their living environment, became known as the Oposa Doctrine.”

“Many human lives are at stake, making the issue one of a violation of human rights.”

It was only a matter of time before this principle would be applied in the arena of climate change.

That time has come.

In late 2013 Urgenda filed a lawsuit against the State of the Netherlands charging that it has taken insufficient action to prevent dangerous climate change. The Dutch government is thus endangering not only the living environment of future generations, but also life itself,” according to the brief, which strongly echoes Oposa’s original complaint.

“This has gone well beyond a concern for drowning polar bears,” attorney Roger Cox said at the time. “Many human lives are at stake, making the issue one of a violation of human rights.”

Court cases have been filed in Belgium and the United States, as well, in the quest for a robust climate policy. And earlier this month, representatives of Fiji, the Solomon Islands, the Philippines, and other nations declared their intention to bring collective legal action against the largest contributors to climate change.

Could the law play a role in tackling climate issues?

Whether the law can really make a difference on climate issues is still up for debate. Climate change law is a very young field and the cases referred to above have yet to be adjudicated.

The underlying question is what governments are actually obliged to do from a legal perspective to cut their carbon emissions. A group of prominent lawyers and scientists has been trying to answer that question for the past few years. It was established by the lawyer Jaap Spier and the philosopher Thomas Pogge and has representatives from every continent. Spier is a professor of liability law and advocate-general at the Dutch Supreme Court in The Hague; Pogge is a professor of philosophy and international relations and the Director of the Global Justice Program at Yale University.

“Up until now, lawyers have not delineated what exactly must be done by whom to battle the problem of climate change,” Spier said, during an interview in his office at the Supreme Court building in The Hague. “We wanted to gain some clarity about the obligations states and enterprises have.”

After holding meetings in The Hague, New York, London, and Oslo, the group presented the results of its years of deliberation in March: the Oslo Principles, named for the city in which they were ratified. According to the document, under existing law, governments and businesses already have a profound moral and legal duty to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

The Principles themselves do not establish any legal obligations; they are more of an opinio juris, a legal vision that has been argued. It’s meant to serve as a guide for anyone pursuing legal action in climate matters and as a reference point for judges adjudicating climate cases. They can use the Principles as a source of information on the legal principles that apply in climate issues.

Deforestation in the rainforests of Sumatra, Indonesia. Photo by Kemal Jufri/AFP

Why climate change is a matter for the courts

“If we allow climate change to continue unchecked, it will result in profound violations of human rights,” says Pogge during a Skype interview with him from his hotel room in Tel Aviv, where he is on a business trip. “Take the right to access to food and water. That is seriously threatened by climate change because of the extreme weather patterns, for instance.”

“Judges are in the unique positions of being able to rein in politicians.”

In February a group of NGOs sent the U.N. a letter requesting that it address the relationship between human rights violations and climate issues. “Climate change is a global injustice to present and future generations, and one of the greatest human rights challenges of our time,” according to the signatories. Poorer countries, who have contributed the least to climate change, face the heaviest impact.

The rationale behind the Principles is simple: any parties who contribute to climate change are violating human rights. States can thus preeminently be held to account for this, because it is their duty to protect human rights.

The Principles are explicitly intended to engage judges and the courts in the problem, according to Pogge. “Judges are in the unique positions of being able to rein in politicians,” he points out. “If a court says that the government has to do, or stop doing, something, then it has to obey.”

A just principle for all

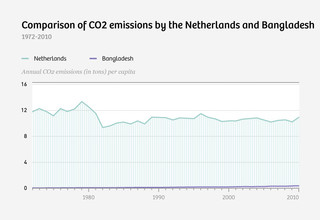

But what criteria should judges use to decide what countries are supposed to do? The group sought to define a single principle that could be applied to all of the countries in the world. The “carbon budget” was a possibility: that is the amount of CO2 we can continue to emit and still have a hope of keeping planet warming under the critical limit of 2°C. A per capita share of the acceptable emissions level can be derived by dividing this budget across the entire world population. Underdeveloped, densely populated countries come in well under this level and should therefore not, as a rule, have to curtail their emissions according to the Principles.

The same is not true for developed countries. The Netherlands would need to reduce its emissions more quickly than, say, Bangladesh, under the Principles’ guidelines. That does indeed seem most just, since the Netherlands has traditionally emitted much more greenhouse gases, something that helped it achieve its current economic prosperity, whereas the reverse is true for Bangladesh. Moreover, countries such as the Netherlands can better afford to cut emissions.

Source: World Development Indicators

By formulating a single rule that applies to all countries, Spier and Pogge hope to eliminate the uncertainty regarding countries’ obligations. Although there are exceptions, in the vast majority of cases, the countries that currently emit the most are also the biggest contributors to climate change. Yet they only feel obligated to adhere to the emissions reductions they have set for themselves – which are not collectively sufficient to prevent climate change and its dangers. The countries in the legal danger zone are primarily Western countries, which currently emit more greenhouse gases than permissible under the Principles.

What’s legal one minute, could be illegal the next

Ideally for Spier and Pogge, the Principles would take precedence without having to be enforced through court cases, for the simple fact that they represent what is just. But the two activists are realistic enough to realize that the doctrine will only truly have an impact once a judge rules in accordance with the underlying principles they have outlined in writing (because the Principles would then become jurisprudence, instead of merely an “opinion”).

This will, of course, require a sympathetic judge, Spier acknowledges, because up until now liability law has rarely been applied to climate change.

But what is legal one moment can be illegal the next, because the judge says so. Just as in the Oposa case – and perhaps in the climate cases now in the courts.

Deforestation in the Amazon, in Brazil. Photo by Raphael Alves/AFP

Government obligations

But even if a judge in the Netherlands or elsewhere is prepared to interpret existing law in such a way as to eliminate the injustice of climate change, obstacles remain. Judges cannot advocate for “human rights in general,” for instance. And it is difficult to demonstrate specific violations of human rights that have been caused by climate change. How do Dutch carbon emissions, for instance, contribute to a greater risk of flooding in Bangladesh? How does that specifically lead to a shortage of drinking water for local residents there?

“Our emissions have an impact on the climate problem. That is reason enough to tell the government, ‘You have an obligation to do your job better.’”

“These are interesting questions when you start talking about damages,” says Spier. “But if we are talking about solving the problem, then you don’t have to look far. Our emissions have an impact on the climate problem. That is reason enough to tell the government, ‘You have an obligation to do your job better.’”

But what if it costs a country a lot of money to reduce emissions? Spier acknowledges that concrete investments will always be part of the political battle. “We resolved that by having the obligations be graduated. The countries’ top priority is to reduce their emissions to the extent that these exceed the allowable limit.” That means they have to take action when it starts costing them money.

But is the responsibility of a small country sufficient to warrant legal action? In 2014 the Netherlands was only responsible for 0.52% of global CO2 emissions, for instance. “You could say that the contribution of a particular country is too small,” Spier says, “and that that country is therefore not under any legal obligation to cut its emissions. You could maintain that, but I do not consider it right. There are countless situations in which very small contributions can still be considered sufficient to trigger particular obligations.”

The soft power of the law

The Principles should be viewed as more than merely a legal device, however, according to Pogge. People become motivated to take action and ramp up the pressure on politicians when they see a practice as being either fair or unfair. “We must never underestimate the power of ideas,” he exclaims. “Just think back to the civil rights movement in the United States, when people decided [...] that black people deserved the same opportunities as white people. That could happen here, too: if people recognize that cutting emissions is the fair thing to do, it could prompt them to take action.”

The total amount of CO2 we can continue to release into the atmosphere is limited, and it is not fair for one country to account for a greater share of the allowable carbon emissions than another. Pogge goes on, “What if people were to say, ‘Yes, I know that the United States is more powerful than Bangladesh, but it is unfair of it to use that power to grab a greater share of the remaining carbon emissions than Bangladesh.’”

“The law is a living instrument,” says Spier. We can use it to frame the discussion about climate change in terms of what is equitable.

It is not equitable for us, within just a few generations, to destroy the climate for all the generations that come after us.

Palm oil plantation in what used to be rainforest in Sumatra, Indonesia. Photo by Ulet Ifansasti/Getty Images

The winning card in a good case is a strong story

Oposa, back in the Philippines, has always prided himself on his storytelling abilities, with the law as his medium. His influence has been profound.

Not much happened initially after the judgment from the Supreme Court in his country. The judge of the administrative court was asked to once again look into the logging concessions, but the case faded away, and Oposa did not pursue it further. He already had his trump card: a public judgment from the highest court in the land that generated a considerable amount of media attention and public pressure. The responsible government minister had already used that pressure during the court case to revoke a large number of concessions. No new commercial licenses for logging have been issued in the Philippines since 2011, and despite the fact that lumber is still illegally harvested, there are some hopeful signs of recovery.

After the forests, Oposa turned his attention to the waters. In 1999 he won a remarkable victory in a case against the government of the Philippines and pollution in Manila Bay. The Supreme Court ruled that 12 government agencies had to partner together to clean the bay and that they had to submit action plans and report regularly on their progress to the court.

Oposa had once again managed to force the government to start acting responsibly by taking them to court.

It remains an inspiring prospect.

—Translated from Dutch by Nina Woodson

More from The Correspondent:

Poverty 101: How can we end global poverty once and for all?

By 2030 the world must be free of extreme poverty. The question is how? Of course there’s no single answer. In this crash course on global poverty, we bring together as many answers as we can. We’ll look at the extent of the problem, the causes, and possible solutions.

Poverty 101: How can we end global poverty once and for all?

By 2030 the world must be free of extreme poverty. The question is how? Of course there’s no single answer. In this crash course on global poverty, we bring together as many answers as we can. We’ll look at the extent of the problem, the causes, and possible solutions.

Climate Change 101: Our future on a warming planet

Right now, it looks as if life on earth is going to get a lot more uncomfortable, thanks to the effects of global warming. But it’s precisely in periods of great change that our decisions, our actions – and the stories we tell one another – make the biggest difference. In this crash course, we explore why global warming is dangerous and what’s being done to put a stop to it.

Climate Change 101: Our future on a warming planet

Right now, it looks as if life on earth is going to get a lot more uncomfortable, thanks to the effects of global warming. But it’s precisely in periods of great change that our decisions, our actions – and the stories we tell one another – make the biggest difference. In this crash course, we explore why global warming is dangerous and what’s being done to put a stop to it.

How the world managed to set common goals (though we ended up with quite the list)

Conceived in back rooms fifteen years ago, they have determined how we help the world move forward – the U.N. Millennium Development Goals. Now the entire world can put in its two cents as new goals are drawn up. But is that such a good idea? Here’s our reconstruction, with a view to the future.

How the world managed to set common goals (though we ended up with quite the list)

Conceived in back rooms fifteen years ago, they have determined how we help the world move forward – the U.N. Millennium Development Goals. Now the entire world can put in its two cents as new goals are drawn up. But is that such a good idea? Here’s our reconstruction, with a view to the future.