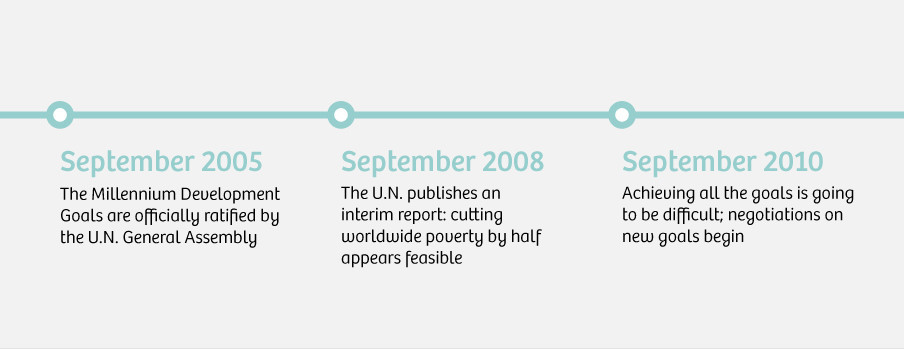

According to Ban Ki-moon, Secretary-General of the United Nations, we are living in a special year. Because now, in 2015, the world has “a unique opportunity” to do something that has "never been done before": completely eradicate poverty.

How? By setting clear, concrete goals to improve the world in the coming fifteen years. They are called the Sustainable Development Goals.

Wait – where have we heard that before?

Kofi Annan, Ban’s predecessor, also thought we were living in a special year. Back then, in 2000, the world had a ‘ "unique opportunity" to do something that had "never been done before": eliminate poverty.

How? By setting clear, concrete goals to improve the world in the coming fifteen years. They were called the Millennium Development Goals.

History repeats itself, which isn’t surprising because poverty, hunger, and child mortality have not been eliminated. So this year we need new goals.

Better goals. Goals that will actually help the world move forward. Sustainable goals, with a capital S.

This article is not about whether the Millennium Development Goals were achieved. The answer to that question is often the result of juggling with numbers.

Nor is this article about whether there’s any point to setting such goals. After all, we’ll never know what the world would look like without Millennium Development Goals.

What we are going to look at is how you go about setting such goals. Because it’s quite a challenge: how do you develop an agenda that the whole world can live with?

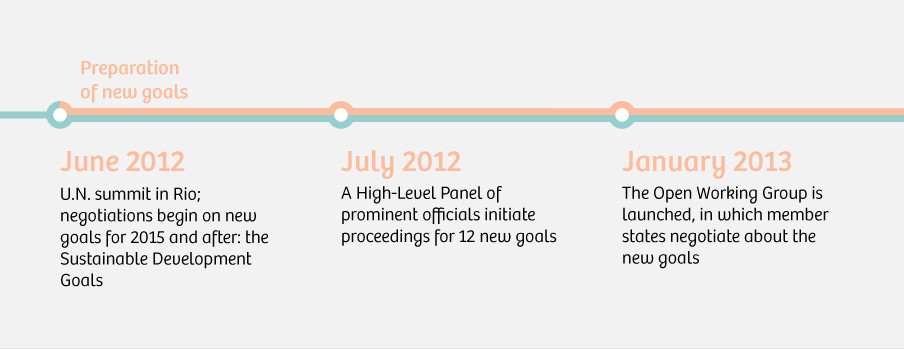

Since 2012 people have been working on new goals for 2030, the successors of the Millennium Development Goals. What did the hundreds of negotiators learn from the past fifteen years? We spoke with past and present negotiators about the challenges. Here’s what they had to say:

Challenge 1. How do you arrange for the whole world to have a say in the matter?

It’s the year 2000 and the new millennium is about to begin. We’re afraid that our computers are going to crash, the euro doesn’t exist yet, but the Twin Towers do. As for eradicating poverty, that’s essentially an ad hoc effort. Major conferences are held frequently, but they always focus on a single issue. How to get all children to go to school, for example. Or how to get women to contribute to the development of your country. But there is no coordinated agenda.

Illustration by Tjarko van der Pol

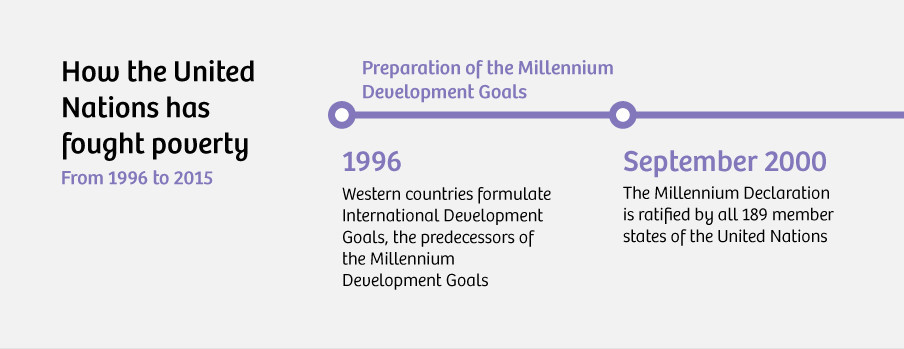

High time to change that, thinks U.N. chief Kofi Annan. Under his leadership the United Nations takes the initiative to develop a concerted plan to eradicate poverty. And what could be a more symbolic occasion than the new millennium? And indeed, all 189 of the U.N.’s member states signed the Millennium Declaration in 2000: a solemn pledge to really make an effort this time to improve the world. But as is often the case with good intentions, the declaration was already gathering dust six months later.

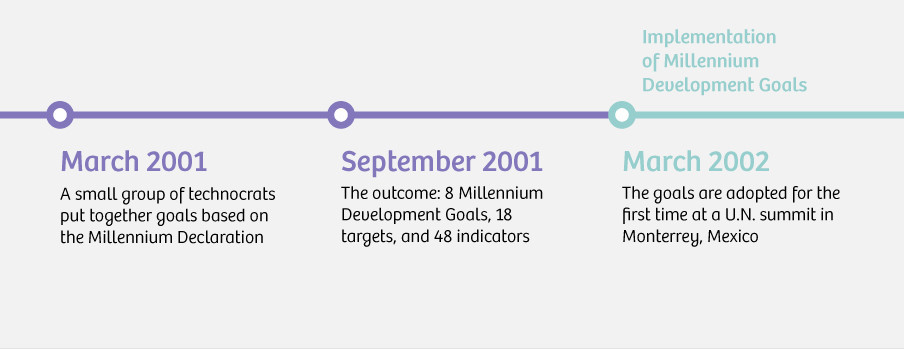

Annan decided to intervene. A group of technocrats were summoned to make the targets pledged in the declaration more tangible. That group drew up the Millennium Development Goals behind closed doors. Eight in total.

There’s plenty of conjecture about exactly how it all transpired: some say that the goals were jotted down on a beer coaster in a smoke-filled bar. Others claim that the technocrats toiled non-stop for two days in the basement of the U.N. headquarters on 1st Avenue in New York. Jan Vandemoortele, the Belgian director of UNDP’s poverty group at the time, was one of those present. He speaks of the leadership the group had within the U.N. “You can discuss things in back rooms that you would perhaps never bring up in public.” A Dutchman who was part of this select group describes the “independence” and “freedom” they were granted while drafting the goals.

The goals were an extension of the West, which was once again determining what was best for the rest of the world

But the technocrats were not thanked for this “freedom” and “leadership.” The U.N. member states – particularly the developing countries for which the goals were intended – were not amused to discover that they weren’t part of the process. The goals were an extension of the West, which was once again determining what was best for the rest of the world.

As it turns out, few countries were interested in really committing themselves to achieving the goals. It was only after a couple of years, when it became clear that Western donor money would actually be distributed based on the goals, that there was more willingness to use the goals as a guiding principle.

But now it’s 2015. Emerging economies such as Brazil and India have an increasingly strong voice on the world stage. The paternalistic way in which the goals were conceived in 2000 is no longer in keeping with the times. “When we started to think about new goals, the developing countries sent a clear message: you got away with that once, but you’re not gonna get away with it again,” says Kitty van der Heijden, a diplomat who was involved in discussions about the new goals on behalf of the Dutch government.

Lesson number one for negotiators was therefore: the decision-making process has to change. More people have to have a say, and certainly the countries whose development is at stake.

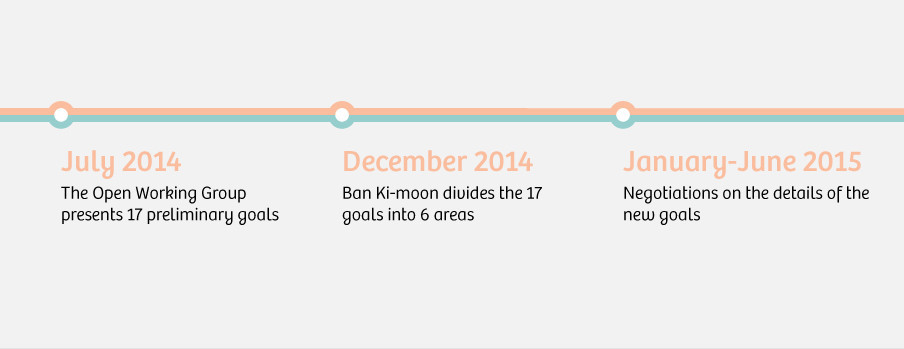

And so it transpired these last years. Unlike with the Millennium Development Goals, this time it’s not U.N. technocrats determining the goals but governments. That has turned the new goals into a political game. Instead of two days in a basement, negotiations have been going on for over three years this time round. And they’re not there yet.

From eight to seventeen goals

Virtually anyone who wants to can offer their input now: non-governmental organizations (NGOs), businesses, academics, regular citizens, you name it.

What kind of an impact has the new approach had so far?

The preliminary results were presented in August 2014. This time it wasn’t a list of eight goals but a list of seventeen. Pretty much anything you can think of to improve the world is on the list.

Still number one: eradicating poverty. But now there are also goals to protect the oceans, make cities safer, promote sustainable energy, and ensure access to justice.

So the most important lesson has a flip side: a proliferation of goals. For example, who’s going to be able to recite goal fifteen: “Protect, restore, and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss?”

Because no matter how elitist the process of developing the old goals was, they did succeed in easily conveying promise to the world. Everyone from New Delhi to New York could understand and remember them.

The eight goals were a to-do list that everyone could use. Today’s 17 goals read like a seven-year-old’s wish list. There’s no end to it. How can you explain a list like that to the world, let alone implement it within fifteen years?

Challenge 2. How can we turn universal goals into national goals?

It was crucial, for the goals to succeed, that governments in developing countries adopt them as policy. But Nicole Rippin, who works at the German Development Institute, argues that the impact of the Millennium Development Goals on national policy in developing countries was “pretty mediocre.”

The goals did have a major impact on policy in Western donor countries. They became the guiding principle for how development budgets in the West were disbursed.

But sometimes the outcome was strange. Take Millennium Development Goal Six, which focuses on reducing HIV/AIDS and malaria. Devoting attention to these two diseases makes perfect sense in a country where these are the two biggest health problems. But in countries where that’s not the case – but which do rely on Western development aid – it can lead to awkward situations.

Illustration by Tjarko van der Pol

In 2009 in Rwanda, for example, less than 3% of the population was HIV positive. But during that same year 24% of the national health-care budget (largely financed by Western donors) was spend on combatting HIV/AIDS.

It also shows that goals meant for the entire world are not necessarily the best goals for a single country. A given country may face different problems, or the global goals may simply not be feasible there.

Take Burkina Faso. In 2000 about 30% of the country’s children went to school. The idea that all children would attend school fifteen years later – as goal two stipulated – was too farfetched. It’s not particularly motivating if you know for certain that you won’t achieve your goal. And it’s even less motivating when a country is continuously branded a failed state despite making progress.

On top of that, a global indicator can obscure national problems. Poverty has been halved worldwide in the last fifteen years, for example. Time to celebrate at the U.N., because that Millennium Development Goal has been achieved. Except that the goal never would have been achieved without China’s economic growth. Can we attribute the 50% reduction to the goals? And what good is that anyway to countries where poverty has not been halved?

So lesson two of today’s negotiators is clear: Ensure that every country translates the worldwide goals into national goals. So, for example, make ‘promote health care’ the worldwide goal and ensure that countries can choose for themselves whether that means focusing on HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, or obesity.

But this second lesson contains a challenge of its own. How truly ambitious are the goals, if every national government can interpret them as it chooses? And who determines what’s ambitious enough? “Of course, every country wants to be perceived as a success story,” says researcher Nicole Rippin. “So there’s a good chance countries will set the bar low, saying, ‘We have to because of our national circumstances.’”

Moreover, various experts are warning against cherry picking. If it’s clear that a country will never achieve all the goals, then it will start to focus on the easiest goals. Whether these experts’ fear is well-founded will be clear next year, when all countries set national goals.

Challenge 3. How do you ensure the West is on board?

Action by the South, financed by the North: that was the guiding principle in 2000. National governments in developing countries were to carry out the goals, while the West would take care of the funding, and a network of thousands of NGOs would provide support on the ground.

But developing countries protested, wondering why the goals should only pertain to developing countries? The fact that girls attend school in the U.S., certainly doesn’t mean there’s no work left to be done about the position of women. And aren’t there people living in poverty in the United States and France? And is there even such a clear distinction between “developing countries” and “the West” anymore? Singapore, which is a member of the G77 – a power block of developing countries – has a higher GDP than Bulgaria, a member of the European Union.

So who exactly is a developing country here?

Illustration by Tjarko van der Pol

The new goals are meant to apply to the whole world, largely because making development sustainable is something prosperous countries need to commit to. Take cutting CO2 emissions, for instance, investing in sustainable energy, or augmenting the sustainability of food production.

That’s why in U.N. circles we keep hearing how “universal” the new goals are going to be. And that’s reflected in the way the goals are formulated. While the Millennium Development Goals referred to “achieving universal primary education,” the new goals talk about “ensuring inclusive, equitable and quality education, and promoting lifelong learning.” The U.S. is sure to interpret that differently than Burundi, but the ultimate goal is the same.

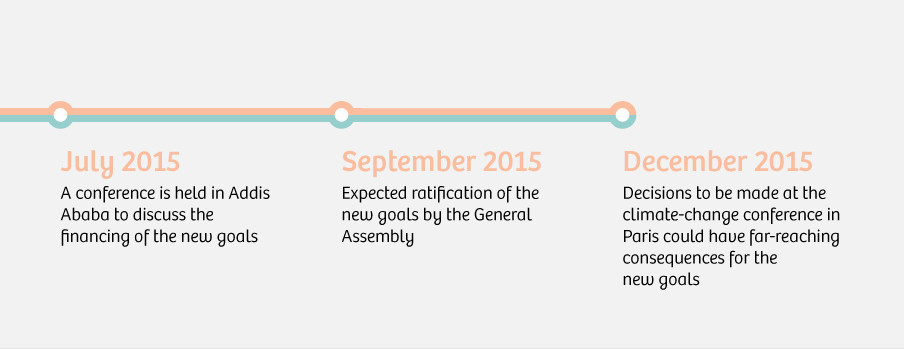

You know what’s coming. This lesson will be a challenge in the years to come, too. Because if as a prosperous country you want to help achieve new goals you can now opt to spend your money on developing your own country or on developing other countries. The major risk of this strategy is that there will be less money left for the poorest countries. This issue will be addressed at the U.N. conference in Addis Ababa this year.

Challenge 4: How can we make these goals sustainable?

It was a close call, but there were nearly seven Millennium Development Goals instead of eight. The group of technocrats that wrote the goals had already shut the door behind them when one of them, head of UNDP Mark Malloch Brown, bumped into the head of the United Nations Environment Program on his way to the exit. “I cursed myself profusely as soon as I realized that we had forgotten to include a goal for the environment,” Mark Malloch Brown would later tell The Guardian.

Because, yes, that’s right, the environment wasn’t really part of it all. It was a goal on the list, but neither the developing countries nor the donors considered it a priority. The fact that one climate conference after another failed didn’t help matters.

Illustration by Tjarko van der Pol

That’s different now: sustainability, which has subsumed the issue of environment, is the buzzword for anything to do with development. When meetings on the new goals first took place in June 2012 in Rio de Janeiro, they yielded a document that contained 384 instances of the word “sustainable.” It’s no wonder that the new goals have been christened the Sustainable Development Goals.

Which is a good thing, of course. It’s not only important to solve today’s poverty problem, you also have to prevent creating more poverty tomorrow. Think of sustainable agricultural methods that won’t deplete scarce farming land, sustainable water supplies to prevent acute shortages in the future, sustainable energy to keep climate change in check, and a sustainable consumption pattern to ensure a fairer and more affordable distribution of food worldwide.

Nonetheless, the last thing many developing countries were waiting for was sustainability in the goals. They said they were afraid that the focus on environmental issues would be at the expense of other societal problems. Of course, there is a connection between climate change and development, but if funds to preserve the oceans come from the same source as those to improve healthcare, then developing countries understand well what’s coming.

This fear was reiterated in the run-up to the new goals as a result of the list of priorities drawn up by the EU – traditionally the most important player in development cooperation. These goals were all related to the environment. “Combining these environmental goals with lifting people out of poverty was a complete disaster,” says Kitty van der Heijden. “In doing so, the EU confirmed exactly what all developing countries feared: all that money is going to go to the green agenda, and nothing will remain for traditional development goals.”

The strong focus on the environment entails another danger as well, concealed in an asterisk. Goal 13 states: “Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts*.” And in the small print at the bottom of the page, we subsequently read: “*Acknowledging that the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change is the primary international, intergovernmental forum for negotiating the global response to climate change.”

In other words, goal 13 – and basically all the other environmental goals – relies on what will be achieved during negotiations at the next climate change conference, due to take place in Paris in December. . What if the conference fails? Does that mean the new goals are doomed too? Virtually all the negotiators we spoke to shared this fear.

A menu for everyone

The way the U.N. draws up development goals – now as well as fifteen years ago – demonstrates just how much has changed in the world: No one can simply shove a plate full of policies in front of developing countries anymore. Western countries can no longer deny their own problems. And climate change cannot be ignored.

Of course it’s good news that lessons are being learned, yet the new challenges are nothing to scoff at either. So what’s the net gain for the world?

The goals are like the menu in a restaurant. In 2000 wealthy countries put together a small menu for poor countries, then disbursed their funds to a limited number of options. Now wealthy and poor alike are creating the menu together, and there are many more options.

But the funds that wealthy countries can spend in the restaurant is unchanged. So they’ll choose relatively less from that larger menu. And he who pays the piper (i.e. the West) still calls the tune.

In the meantime, nothing is definite yet. In the months to come, it will become clear whether the 17 goals will actually be approved by the United Nations, how they will be funded, and whether the world will also back the climate change goals. Negotiations on the details of the new goals are still in full swing.

So will the world seize Ban Ki-moon and Kofi Annan’s “unique opportunity” this year and help lift the world out of poverty in the next fifteen years?

That’s the goal.

—Translated from Dutch by Mark Speer

More from The Correspondent:

Poverty 101: How can we end global poverty once and for all?

By 2030 the world must be free of extreme poverty. The question is how? Of course there’s no single answer. In this crash course on global poverty, we bring together as many answers as we can. We’ll look at the extent of the problem, the causes, and possible solutions.

Poverty 101: How can we end global poverty once and for all?

By 2030 the world must be free of extreme poverty. The question is how? Of course there’s no single answer. In this crash course on global poverty, we bring together as many answers as we can. We’ll look at the extent of the problem, the causes, and possible solutions.

Climate Change 101: Our future on a warming planet

Right now, it looks as if life on earth is going to get a lot more uncomfortable, thanks to the effects of global warming. But it’s precisely in periods of great change that our decisions, our actions – and the stories we tell one another – make the biggest difference. In this crash course, we explore why global warming is dangerous and what’s being done to put a stop to it.

Climate Change 101: Our future on a warming planet

Right now, it looks as if life on earth is going to get a lot more uncomfortable, thanks to the effects of global warming. But it’s precisely in periods of great change that our decisions, our actions – and the stories we tell one another – make the biggest difference. In this crash course, we explore why global warming is dangerous and what’s being done to put a stop to it.

Cutting a deal with the whole world is a messy affair

For four months, research assistant Jan Sluyterman and I interviewed more than forty people involved in the United Nations’ negotiations on development goals for the world. We wondered: How in the world can all countries manage to reach agreement about the future of our planet? A reconstruction.

Cutting a deal with the whole world is a messy affair

For four months, research assistant Jan Sluyterman and I interviewed more than forty people involved in the United Nations’ negotiations on development goals for the world. We wondered: How in the world can all countries manage to reach agreement about the future of our planet? A reconstruction.

Nearly all the world’s relief supplies

pass through this desert

In an unlikely spot in the middle of the desert lies the world’s largest stockpile of humanitarian relief supplies. Blankets, tents, buckets, and bodybags await the next big disaster. But why here, in Dubai? And what are conditions like for the city’s migrant workers? A travel log from a surreal place.

Nearly all the world’s relief supplies

pass through this desert

In an unlikely spot in the middle of the desert lies the world’s largest stockpile of humanitarian relief supplies. Blankets, tents, buckets, and bodybags await the next big disaster. But why here, in Dubai? And what are conditions like for the city’s migrant workers? A travel log from a surreal place.

Ten questions about the goals meant to save the world

All world leaders, from the pope to Angela Merkel, will be in New York this weekend. They’re there to shake on seventeen “sustainable goals” that aim to make the world a better place by 2030. What can we expect from the summit?

Ten questions about the goals meant to save the world

All world leaders, from the pope to Angela Merkel, will be in New York this weekend. They’re there to shake on seventeen “sustainable goals” that aim to make the world a better place by 2030. What can we expect from the summit?