New York resembles one big crowd barrier this weekend. The pope, Barack Obama, Angela Merkel, Mark Zuckerberg, Malala Yousafzai, and Shakira are there, as are thousands of journalists from all over the world.

They’re gathering for the Sustainable Development Summit. During the summit member states will ratify the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. It’s a list of seventeen goals that all U.N. member states agree should be achieved so that the world will be a better place in 2030 than it is today.

What does it mean to ratify development goals? And are these goals really going to improve the world? Here are answers to the most important questions.

The world will be a whopping seventeen goals richer after this weekend. But wait a minute, didn’t we already have Millennium Development Goals?

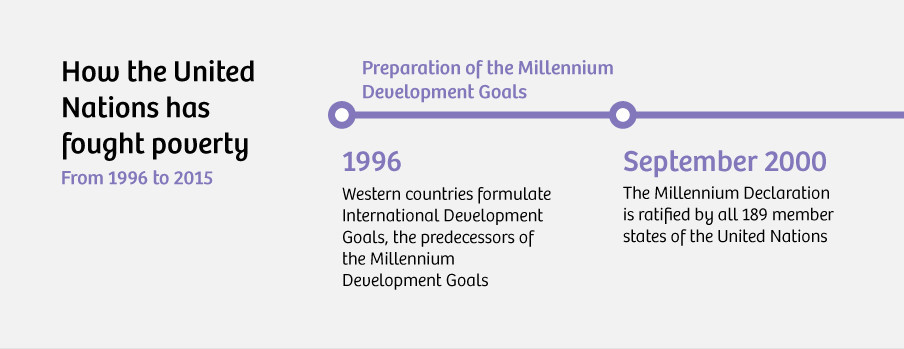

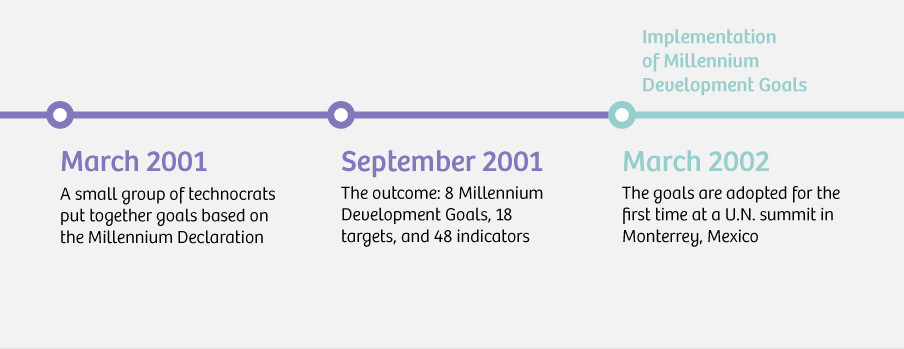

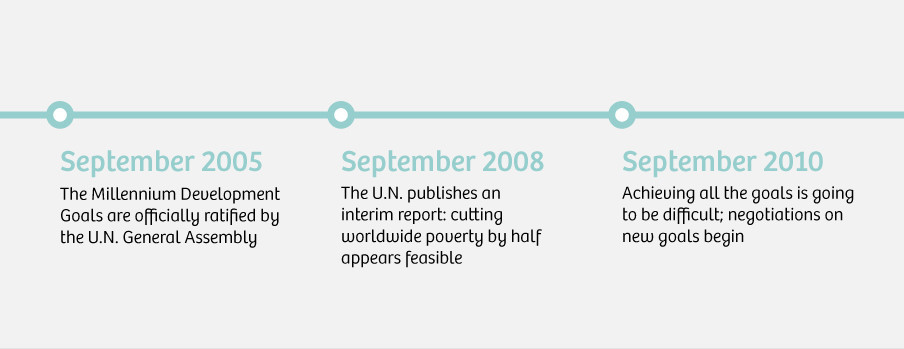

That’s right. Until 2000 there was no international, coordinated agenda for combatting poverty. The new millennium was seen as the perfect occasion to give new impetus to the fight against poverty. This impetus took the form of the Millennium Development Goals. Eight goals, the primary aim of which was to cut global poverty in half in fifteen years.

How? National governments in developing countries would implement the goals, the West would arrange funding, and a network of thousands of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) would provide practical support.

And? Did we achieve the Millennium Development Goals?

The deadline for the Millennium Development Goals is December 31 of this year. Excellent progress has been made in many areas. For example, the number of children attending school has increased significantly; extreme poverty seems to have been cut in half; as has the number of children dying before the age of five. Moreover, the segment of the world’s population with no access to clean drinking water has been reduced by half as well.

We’re still far from achieving universal access to healthcare. While the number of malnourished children worldwide has decreased substantially, it has not yet been cut in half.

But there are a number of points to consider. For example, the only reason why global poverty has been halved is China’s economic growth. The poverty rate in Africa has anything but halved.

And several goals have not been achieved. We’re still far from achieving universal access to healthcare. While the number of malnourished children worldwide has decreased substantially, it has not yet been cut in half. And 2.5 billion people still have no access to hygienic sanitation facilities, 1 billion of whom only have access to open sewers.

What’s more, the data that’s supposed to measure progress on the goals is often unavailable or unreliable.

Okay, so these goals are succeeding the Millennium Development Goals?

To a certain degree, yes. Poverty has still not been eradicated, so there seemed to be a need for a new list of goals. The deadline this time is 2030.

There are two major differences with the previous goals.

- The old goals were about development in the strict sense of the word: fighting poverty, improving healthcare, children attending school, etc. The new goals take a much broader view of development: they are about climate change, peaceful cohabitation, and responsible production and consumption. The new goals stress that it’s pointless to focus on fighting poverty if there is a war raging. That there’s no point improving healthcare if the effects of climate change means people to have nothing to eat. The keyword of the new goals is sustainability.

- The old goals were about traditional development aid: Poor countries had to achieve the goals, while wealthy countries would foot the bill. But the new goals concern the entire world. All countries have to work on sustainable development now, including the wealthy ones.

But hold on. Who determines which goals the world is going to set?

That’s probably the most important question. The Achilles heel of the Millennium Development Goals was that they were conceived by a small group of white men in the basement of the U.N. headquarters. Poor countries, which were the focus of the goals after all, had no say whatsoever in the matter. So they felt that the goals had been shoved down their throats, and as a result for a long time they weren’t very enthusiastic about working on them.

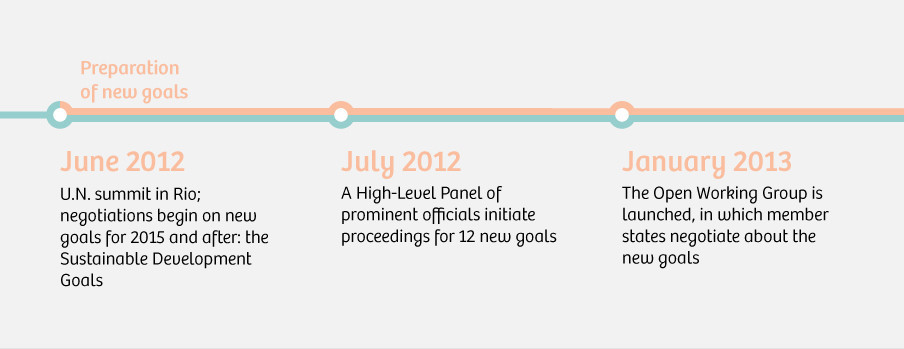

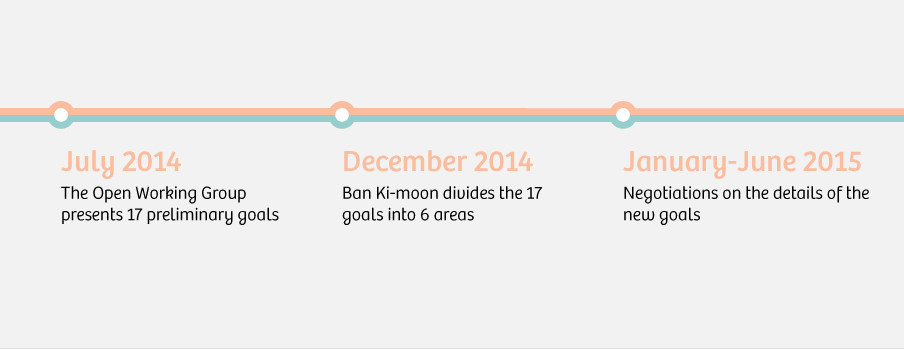

Things went differently with the new goals. An “open working group” was launched, so the entire world to have their say. NGOs, businesses, academics – all kinds of experts were rounded up to provide input. Seven million questionnaires were sent to world citizens to find out what kind of a world we actually want in 2030.

But the really unique thing about the open working group was that countries didn’t negotiate in their traditional alliances, but in troikas. The Netherlands, for example, shared a seat with Australia and Great Britain. Cyprus, the United Arab Emirates, and Singapore worked together, as did Nepal, Iran, and Japan. As a result, countries that are normally obscured by their larger allies (such as small island nations), suddenly had a voice.

Of course, for a long a time it was unclear whether so many countries could agree on such a comprehensive agenda. It even came to blows between the diplomats from Iceland and Saudi Arabia. But in the end it succeeded. This was seen as a major victory in U.N. country.

So who’s going to foot the bill for achieving the new goals?

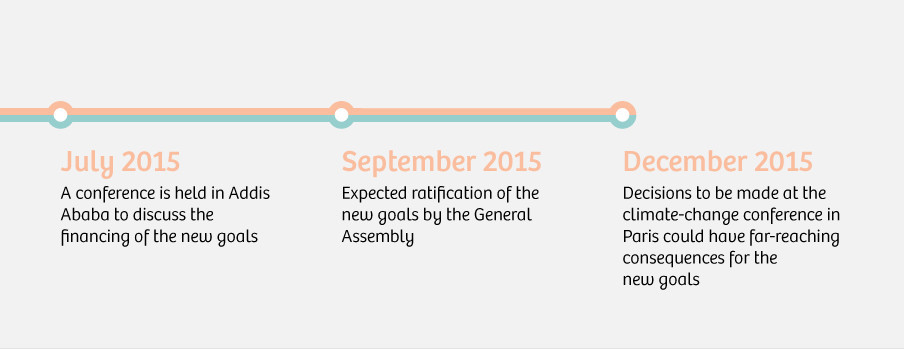

Last June a conference was held in Addis Ababa to come up with an answer to this question. But the world leaders didn’t come up with anything particularly concrete.

One thing’s for sure: governments won’t be able to cough up enough money on their own to achieve all the goals (there wasn’t even enough money available for the eight Millennium Development Goals). So we’re going to need the assistance of the private sector and NGOs. The code word is public-private partnerships (PPPs). We’ll have to wait and see exactly what shape these partnerships are going to take in the coming fifteen years.

By the way, isn’t seventeen goals a bit over the top?

Yes. You could fit the Millennium Development Goals on a refrigerator magnet, but the Sustainable Development Goals will take up your whole fridge.

But if the whole world gets to have a say, then you can’t expect a small list. So, yes, it’s a long list, but it is one that’s backed by all of the countries.

Of course, it’s not realistic to think that every country will achieve every goal. Each country will choose a few priorities from the long list and focus on them. It’s not clear, however, how to prevent countries from cherry picking (and only work on goals that are easy to achieve).

Are countries obliged to do something with the goals?

Obliged is a big word. Ultimately it’s up to the countries themselves whether or not to incorporate the goals in their policy. But it’s certainly important to take these goals seriously in terms of maintaining your international reputation.

Ratifying the goals this weekend will be a formality. But the fact that so many world leaders have chosen to travel to New York for the occasion does show that it’s serious business. Moreover, the pope’s speech will help to give the goals greater weight – he is still considered an important leader, particularly in many developing countries.

What would make these new goals a success?

Actually these goals already are a success. Not so much for their content, but more for the process. It’s the biggest agenda that the United Nations has ever agreed on.

That’s quite an accomplishment in the international political arena, where “agreeing on something” is often a task in itself. But of course that’s meaningless to people who still live in extreme poverty.

It’s not clear yet exactly how we’re going to measure whether all of the goals are achieved. At this point in time, a technical team from the U.N. is putting together measurable “indicators” for each goal. There will probably be more than five hundred. The deadline is March 2016.

Until then, there is above all a sense of relief in U.N. circles that the goals have been ratified. And that there’s a list which everyone is behind – at least on paper.

The question is how will we look back on it all in fifteen years? And will the world have moved forward thanks to or despite these goals? Even the greatest optimists won’t speculate on that.

—Translated from Dutch by Mark Speer

More from The Correspondent:

Poverty 101: How can we end global poverty once and for all?

By 2030 the world must be free of extreme poverty. The question is how? Of course there’s no single answer. In this crash course on global poverty, we bring together as many answers as we can. We’ll look at the extent of the problem, the causes, and possible solutions.

Poverty 101: How can we end global poverty once and for all?

By 2030 the world must be free of extreme poverty. The question is how? Of course there’s no single answer. In this crash course on global poverty, we bring together as many answers as we can. We’ll look at the extent of the problem, the causes, and possible solutions.

Climate Change 101: Our future on a warming planet

Right now, it looks as if life on earth is going to get a lot more uncomfortable, thanks to the effects of global warming. But it’s precisely in periods of great change that our decisions, our actions – and the stories we tell one another – make the biggest difference. In this crash course, we explore why global warming is dangerous and what’s being done to put a stop to it.

Climate Change 101: Our future on a warming planet

Right now, it looks as if life on earth is going to get a lot more uncomfortable, thanks to the effects of global warming. But it’s precisely in periods of great change that our decisions, our actions – and the stories we tell one another – make the biggest difference. In this crash course, we explore why global warming is dangerous and what’s being done to put a stop to it.

Why we know less about developing countries than we think

Africa boasts five of the world’s ten fastest-growing economies. And the percentage of poor and malnourished people worldwide has been cut by half in the last 25 years. Poor countries seem to be prospering – but is the rosy picture accurate? I crunched the numbers, and here’s the truth: when it comes to developing countries, there’s a lot we don’t know.

Why we know less about developing countries than we think

Africa boasts five of the world’s ten fastest-growing economies. And the percentage of poor and malnourished people worldwide has been cut by half in the last 25 years. Poor countries seem to be prospering – but is the rosy picture accurate? I crunched the numbers, and here’s the truth: when it comes to developing countries, there’s a lot we don’t know.

This is what hunger does

It sounds brutal, but three groundbreaking studies in World War II taught us a lot about starvation. Today, more than 800 million people are chronically malnourished. Two billion more suffer from “hidden hunger.” What does hunger do to those affected?

This is what hunger does

It sounds brutal, but three groundbreaking studies in World War II taught us a lot about starvation. Today, more than 800 million people are chronically malnourished. Two billion more suffer from “hidden hunger.” What does hunger do to those affected?