The sun hangs high in the sky above the blindingly white sand of the beach. The azure sea lies on one hand, while on the other, rock faces erupt steeply. It’s no coincidence French colonists called the island of Hispaniola the “Pearl of the Antilles.” It produces rich quantities of coffee, sugar, and rice.

Half of that wealthy island is now Haiti.

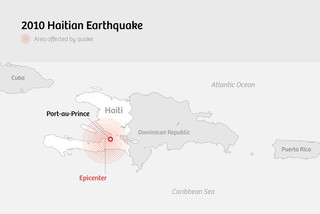

Which might surprise you, since many of us hear about Haiti mostly in connection with human misery. Like the devastating earthquake in 2010, or the cholera epidemic that swept the country in its aftermath. You might know it as the poorest country in the western hemisphere.

No wonder many Haitians believe that the country has been cursed since declaring its independence in 1804. When the Haitians fought and won their independence from France (the first slave colony to do so), a Vodou legend holds that a pact was made not only with benevolent spirits, but with the devil as well. The pact gave Haitians a state of their own, but it also brought them more than two centuries of poverty, coups, dictatorships, and natural disasters.

Within the miserable continuum of Haitian history, the 2010 earthquake – which killed 230,000 people and rendered 1.5 million homeless – was not only a fresh tragedy, but also (as terrible as it sounds) a fresh opportunity. Or, as many Haitians put it: “It’s the best thing that ever happened to Haiti.”

As a result of the disaster, Haiti gained two things that were in short supply in the country up to that point: widespread media attention and money. The island nation was finally in the international spotlight. People around the world collected teddy bears, used clothing, and even celebrities to help the cause. In total, the island received some 7.5 billion euros in aid. To put it in perspective: in the year before the quake struck, Haiti had a gross domestic product of 5.5 billion euros.

At the peak of the humanitarian response, over 10,000 aid organizations were active in Haiti – that’s one for every 900 people. The result was chaos: redundant efforts, competition, a lack of coordination, oversight and accountability. As the U.N. stabilization mission MINUSTAH was being expanded, some blue helmets from Nepal brought the cholera bacteria along with them.

What ensued was a disaster within a disaster – a cholera epidemic that is still raging today.

Today, January 12, is five years to the day since the earthquake struck. The camera crews and celebrities have all gone home; the international sources of funds have turned their attention to other crisis areas; now the teddy bears are being shipped to West Africa or Syria. A few crews remain, working to cover the massive anti-government protests of recent months. But these haven’t made global headlines.

It seems a good moment to stop and take stock. Haiti was a country in rubble and ruin. And a country in ruin is like a giant puzzle that needs to be put back together.

If we reassemble the pieces of Haiti now, what picture will we be looking at? Has the earthquake finally broken the nation’s pact with the devil?

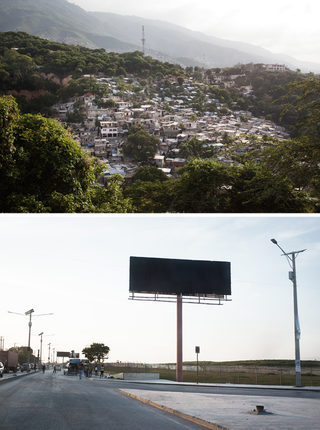

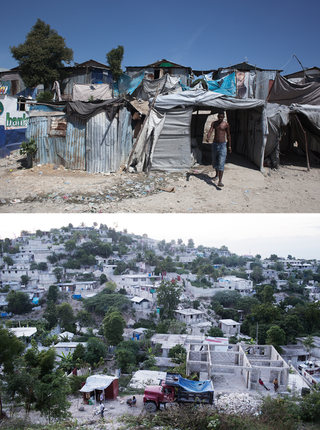

The hilly Haitian capital, Port-au-Prince. Photos by Pieter van den Boogert

First piece of the puzzle: the government

The fences around the presidential palace in Port-au-Prince have been screened off with green tarps. Behind them, hidden from the sight of passers-by, lies a crater. The palace – which residents of the capital referred to as the wedding cake – literally collapsed like a cream puff back in 2010. A new palace has yet to be built.

And it wasn’t just the palace: the earthquake wiped out practically the entire civil service apparatus. Around 25% of Haitian government officials were killed, while in Port-au-Prince only two of the twenty-seven government buildings remained standing.

Yet the government that collapsed was built on shifting sand long before the quake hit. Since the fall of the father-son dictatorship of the Duvaliers in 1986, Haiti has seen over a dozen heads of state.

These often seized power through a military coup. The current president, Michel Martelly was elected after the earthquake in hopes he would get the country back on track. Unfortunately, the 2015 Transparency International corruption index still ranks Haiti number 161 out of 175 countries.

This track record is the reason why only 1% of emergency aid funding was issued to the Haitian government directly. The rest of the money was given to aid organizations. And for development aid, it’s the same story: between 2014 and 2014, only 9% of funding went to the government. The assumption being that if the money was given to the government, it would never reach the intended recipients.

Which is precisely the problem, according to experts including Haitian economist Camille Chalmers, who works with the Haitian Platform to Advocate Alternative Development (PAPDA). “By not giving money to the government, the state is in fact being further weakened: educated Haitians are taking jobs with international organizations instead of in government. Ministries no longer have influence on the sectors for which they are responsible.”

Top: Haitian police officers patrol in Caradeux, accompanied by their U.N. trainers. Below: In many areas of Port-au-Prince, the rubble has yet to be replaced with new buildings. People sometimes avoid rebuilding out of a fear of ghosts, in accordance with their Vodou religion. Photos by Pieter van den Boogert

The thousands of aid organizations in Haiti have now assumed tasks that should rightfully be carried out by its government. According to Peter de Clercq, U.N. humanitarian coordinator in Haiti, the problem lies primarily in transitioning from emergency aid – the life-saving phase – to development aid – the life-improving phase.

The model built around aid organizations must yield the floor to a model in which the country’s own government takes priority. “We haven’t quite found the magic bullet to solve that one yet,” De Clercq admits.

That the houses all have the same dull cement color isn’t because people can’t afford paint; it’s because you don’t have to pay taxes on a house until it’s finished – until it’s painted.

The economist, Chalmers, uses a Creole saying when describing the Haitian government: sak vide pa kanpe, an empty sack can’t stand up. And the help organizations aren’t the only thing keeping the sack empty. In Haiti, hardly anyone pays their taxes. That the houses all have the same dull cement color isn’t because people can’t afford paint; it’s because you don’t have to pay taxes on a house until it’s finished – until it’s painted. The slogan of the Haitian electricity supplier seems telling: “Please pay your bill, so that we can supply your power.”

But would the government be able to perform its duties if the sack were full of money? The simple answer is no. There’s a limit to how much money, aid or otherwise, a weak government will be able to absorb and process. The key is to increase its capacity to do just that.

Of course, this only works when the aid organizations take the government seriously in the first place. Peter de Clercq: “The president of Somalia, Hassan Sheikh Mohamud, once summed it up nicely. He said, ‘Yes, we are corrupt; yes, we are incompetent; yes, there is a lot of lawlessness. But there is only one government in Somalia – and if you refuse to treat us as a government, we will never succeed in becoming one.’” In De Clercq’s mind, the same principle applies to Haiti.

The current political situation in the country isn’t doing Haiti any favors, either. After months of mass protests against the government , due to postponed elections, today will likely be the day the country finds itself without a diplomatically elected government. As of today, President Martelly will rule by decree.

Peter de Clercq, Humanitarian Coordinator for the United Nations in Haiti and Special Representative for the U.N. stabilization mission MINUSTAH. Photo by Pieter van den Boogert

Two Haitian economists. Left: Camille Chalmers. Right: Kesner Pharel. Photos by Pieter van den Boogert

Second piece of the puzzle: the diaspora

In Caradeux, an IDP camp that was set up after the earthquake, three teenage boys are sitting next to one another on plastic stools. Loud kompa music blares from the speakers of a motorcycle taxi. Shortly after the quake, nearly two million Haitians were estimated to be living in this kind of camp; today, some 80,000 still do so.

The boys sit here all day long, they tell me. In the stench of rotting garbage, between houses that aren’t much more than thrown-together heaps of boards, tree branches and moldy tarps. The children clustered around them are literally covered in dirt and flies.

Are the teenagers interested in finding work? “No way, why should anyone work for such little pay?” one of them asks. “I have family in America – they send me money,” another says.

An enormous diaspora is flowing out of Haiti. The United States alone is home to around 915,000 Haitians. Nearly that many have immigrated to the other side of the island, to the Dominican Republic; 200,000 live in Canada; and in France and the Bahamas you’ll find tens of thousands of Haitians. In Miami – less than an hour and a half by plane – there is even a neighborhood known as Little Haiti.

Together, all those Haitian ex-pats are sending huge sums of money home: over 1.5 billion euros annually. In 2013, this accounted for 21% of the GDP. Which means that young people like those in Caradeux have little incentive to get jobs of their own. Over two-thirds of the potential workforce lacks official employment.

Still, an increasing number of Haitians are returning to their home country from the diaspora in order to start their own businesses. People like Duquesne Fednard, who started a company that makes fuel-efficient stoves. The sounds of hammer on metal ring amid stacks of silvery drum stoves in a large shed. Fednard yells to be heard above the racket: “I was so tired of that negative image of Haiti people always seem to have. Seriously, it’s not like we just sit around waiting for other people to solve our problems for us. You need philanthropy, sure, but it can’t be the basis of your economy.”

So where should Haitians look to find an economic driver? To find out, we’ll fit the next piece into the puzzle.

Top: Some 80,000 people are still living in IDP camps like this one. Below: Most Haitians choose not to paint their houses in order to avoid paying taxes on them. Photos by Pieter van den Boogert

Third piece of the puzzle: the economy

All across Haiti, the sidewalks are filled with women. They call them madames Sara: traveling market women, who sit on the ground in the shimmering heat, on picnic cloths covered in sandy eggplants, green beans and plantains. Or they shill baskets full of pèpè: secondhand goods like pens, shoes and books. These women form the backbone of the Haitian economy, representing 80% of informal trade in the country.

This year, Martelly’s government announced that Haiti intends to be an emerging economy by 2030. But they’ve a long way to go yet to reach that goal. In the 2014 Global Competitiveness Report, Haiti made a typically poor showing, scoring in the bottom ten and just above Chad and Yemen.

Which isn’t all that strange for a country that runs almost entirely on aid money and paychecks being sent home from Haitians abroad. So what can be done to change this? Where can Haiti find a new money-making sector? Agriculture is some people’s answer, while others say tourism. Product assembly, mining and a more effective Customs system: these are yet more suggestions.

“We’ll never establish a middle class if everyone with an education catches the first plane to the United States”

Kesner Pharel, the best-known Haitian economist, sees only one potential solution: attracting investors and entrepreneurs. “Of course the government is responsible for part of the problem,” he says. “Money is a coward: it always flows toward the lowest risk. If someone hears about all the conflict surrounding the elections here, they’re not going to invest their money in Haiti.”

But in Pharel’s opinion, part of the trouble lies with the private sector as well. “Right now, people see themselves as simply laborers or farmers – they lack belief in their own entrepreneurial ability. And we’ll never establish a middle class if everyone with an education catches the first plane to the United States.”

‘Haiti: Open for Business‘ is the (therefore fitting) slogan of the Martelly government, visible on billboards dotted along the road from the Port-au-Prince airport. Every effort is being made to spruce up the country’s image – after all, pictures of human misery are hardly fertile soil in which to grow an economy.

And now, slowly and gradually, success stories are piling up to give truth to the slogan. Surtab – a tablet manufactured entirely in Haiti – is one such story. As is Digicel, the company that has made it both possible and affordable to use cell phones in this country. Not to mention the colossal white rectangle towering next to the stately, tree-lined Pacot neighborhood: it’s the 174-room Marriott Hotel.

Pharel: “The arrival of the hotel chain marked a real turning point. When American businesspeople can spend the night here in comfort, they are much more likely to invest in this place.”

But is this idea – successfully doing business in Haiti – a realistic one?

Top: Duquesne Fednard’s factory makes fuel-efficient stoves. Below: New roads in Port-au-Prince. Photos by Pieter van den Boogert

Fourth piece of the puzzle: the infrastructure

BelFwi is a tiny storefront in Petion-Ville, where everything is painted neon orange and green. Haiti’s first and only “fruitbar” – serving smoothies, juices and fruit salads – BelFwi was founded by Katleen Jeanty, a Haitian who has spent a large part of her life living in America. She’s returned, post-earthquake, to try and give the Haitian economy what it so badly needs: a dose of buy local, sell local, in the form of a fruitbar.

“It’s our lucky day,” the boy behind the counter tells me, hitting the button on a blender full of mangos. “The power’s already shut off next door.” The government slogan Haiti: Open for Business doesn’t exactly ring true yet, if you ask Jeanty.

The first problem is electricity, which is completely unreliable and exorbitantly expensive. A kilowatt-hour costs 23 cents in Haiti, compared to 14 cents on the other side of the island, in the neighboring Dominican Republic. “It’s ridiculous to have to spend more money on electricity than on paying your employees’ wages,” Jeanty says.

There’s no land title registry in Haiti. If you buy a piece of land, someone else might just show up with an equal claim to ownership of the property

Problem number two is the bureaucratic infrastructure. There are an impressive twelve steps to registering a new business in Haiti. “I thought I was going to lose my mind,” Jeanty laughs. “There was one office I had to go back to six times, because the only person who could give me a certain stamp was out of the office every time I went.”

President Martelly promised to reduce the number of steps from twelve to two, but this is where an earlier puzzle piece fits in: in order to implement that kind of reform, parliament – currently paralyzed by the postponed elections – must first approve the proposed changes.

And we haven’t even talked about the physical infrastructure yet, the thing you need to get your goods from point A to point B. Out of all the “highways” in Haiti, only half are paved. When it rains, the rest of the streets turn into swirling rivers of mud that flow into people’s houses. And even when the roads are paved, the potholes are so deep that folks actually drown in them.

There is no garbage collection or underground sewer system in Haiti. Outside of urban areas there are no gas stations: instead, there are little boys selling jerrycans full of gasoline. There’s no land title registry, either. If you buy a piece of land, someone else might just show up with an equal claim to ownership of the property. Getting access to the court system is difficult as well.

Of course, these are all tasks for government. Still, this piece of the puzzle seems to fit neatly between the failing government and the absence of economic development – after all, how is the government supposed to pay for all this much-needed infrastructure?

Hyguette Pierre Mercier, teacher and board member of a small primary school in the Caradeux IDP camp. Photo by Pieter van den Boogert

Haitians from the diaspora who have returned to start their own businesses. Left: Duquesne Fednard from D&E Green. Right: Katleen Jeanty, owner of the “fruitbar” BelFwi. Photos by Pieter van den Boogert

Fifth piece of the puzzle: agriculture

The patch of ground belonging to farmer Fleurisca Malvoisin is screened from the road by a corrugated aluminum gate and a kandelab, a hedge made from interwoven cacti. The laundry is drying on the ground next to the grain; the pigs, tethered out in the open, are lying on the hot sand.

The Haitian agricultural industry was decimated during the 29-year dictatorship of father and son Duvalier. The Duvaliers lowered tariffs on imported American agricultural products from 35% to 3%, flooding the Haitian market with American rice, sugar and coffee as a result. To this day, an egg from the U.S. is cheaper here than a Haitian egg. The extensive deforestation that has completely exhausted the soil only makes matters worse.

Although Haiti was once a fertile, self-sufficient nation, it now imports 55% of its food. In order to help the country to move forward, its agricultural industry – including the infrastructure needed to get the harvest to market quickly – will have to be modernized. That much is clear.

Yet history continues to play an important role in contemporary Haiti. No farmer would even consider taking on work at a large plantation – it would be all too reminiscent of the slavery of the past. This means that every farmer is a smallholder, working for his own subsistence: it’s what previous generations fought and died for.

Fleurisca Malvoisin has a single mango tree to his name, and he’s proud of it.

Farmer Fleurisca Malvoisin prunes his sole mango tree. He is being filmed by a camera crew from the aid organization that provided him with training on how to better care for his tree. Photo by Pieter van den Boogert

Sixth piece of the puzzle: security

On an enormous slab of poured concrete, surrounded by barracks, groups of young men (and the odd woman) stand scattered. They do jumping jacks, sit-ups, push-ups. These are the latest recruits of the Haitian police.

Last year, an impressive 20,000 candidates signed up – that’s nearly twice the current number of officers on the force. The police academy can only accommodate 1200 new recruits each year.

If there is one piece of the puzzle that shows clear improvement since the quake, it’s the security in Haiti. While travel to the country is still not recommended, at least the organized kidnapping gangs are no longer active.

And whereas safety posed an enormous problem (especially for women) in IDP camps like Caradeaux in the earthquake’s aftermath, measures have now been taken to improve security. A permanent police sentry in the camp, for example, and streetlights powered by solar panels.

However much criticism the MINUSTAH peacekeeping force has received, the Haitian police – who they have been training – is becoming (much) more effective every day. Large-scale police violence is a thing of the past; the population is slowly regaining its trust in law enforcement, who sometimes make their rounds by bicycle these days.

Top: New Haitian police recruits being trained in how to cuff an individual. Below: The factory belonging to Surtab, which manufactures its tablets entirely in Haiti. Photos by Pieter van den Boogert

All the puzzle pieces are in place – what do we see?

Many other pieces contribute to make up this Haitian puzzle, of course. Education, for one. Healthcare. The justice system and the U.N. stabilization mission. But no matter how many puzzle pieces you add, the puzzle shows us that no emergency aid can deal with these problems effectively. The trouble with the failing Haitian state lie much deeper, and were present long before the earthquake.

But what picture does this puzzle reveal, to sum up Haiti five years after the earthquake? Maybe it’s an image of the mass protests against the government as it’s being run by President Martelly. Even if the Haitians lack a functional state, they still descend from the first slaves to fight their way to freedom – freedom they now use to mount a protest. They are a proud people, who fought hard to form this nation of theirs. They are proud of their rum and proud of their coffee. And of their protests as well.

Yes, the poverty is dire; but for many people, life today is better than it was before the earthquake struck

Or maybe the puzzle picture shows the tiny school taught by Hyguette Pierre Mercier in the Caradeux camp. Children in maroon uniforms sit on low benches or on the ground, shrouded in billows of dust and sand. For tens of thousands of people, the emergency shelters and tents found in camps like this one have become a permanent residence.

Yes, the poverty is dire; but for many people, life today is better than it was before the earthquake struck. Mercier: “Before the earthquake I taught school in a couple of old buses. Now, at least we got this building from an aid organization.”

Another possibility: the puzzle of Haiti five years after the earthquake will reveal an image of a taptap. These covered pick-up trucks are Haiti’s characteristic, brightly-painted public transportation. The drivers have elevated the decoration of their vehicles to an artform featuring hand-carved and painted figures and slogans. I imagine the taptap on the puzzle driving through the streets of Port-au-Prince, its windows shaped like peace signs. And on the back there’s one word, painted in vivid blue: optimism.

—Translated from Dutch by Liz Gorin

Update January 14, 2015: The Haitian president Martelly has been unable to reach agreement with leaders of the opposition – the parliament has been dissolved and Haiti is currently without a functioning government.

More stories from The Correspondent:

Poverty 101: How can we end global poverty once and for all?

By 2030 the world must be free of extreme poverty. The question is how? Of course there’s no single answer. In this crash course on global poverty, we bring together as many answers as we can. We’ll look at the extent of the problem, the causes, and possible solutions.

Poverty 101: How can we end global poverty once and for all?

By 2030 the world must be free of extreme poverty. The question is how? Of course there’s no single answer. In this crash course on global poverty, we bring together as many answers as we can. We’ll look at the extent of the problem, the causes, and possible solutions.

Nearly all the world’s relief supplies

pass through this desert

In an unlikely spot in the middle of the desert lies the world’s largest stockpile of humanitarian relief supplies. Blankets, tents, buckets, and bodybags await the next big disaster. But why here, in Dubai? And what are conditions like for the city’s migrant workers? A travel log from a surreal place.

Nearly all the world’s relief supplies

pass through this desert

In an unlikely spot in the middle of the desert lies the world’s largest stockpile of humanitarian relief supplies. Blankets, tents, buckets, and bodybags await the next big disaster. But why here, in Dubai? And what are conditions like for the city’s migrant workers? A travel log from a surreal place.

Life after a typhoon – a post-disaster power struggle

A year after typhoon Haiyan hit the Philippines, leaving 6000 dead and 4 million homeless, the arranged marriage between the country and its aid workers is showing signs of strain. The main point of contention: who’s in charge of humanitarian relief? Photographer Pieter van den Boogert and I delved into the workings of the humanitarian aid machine.

Life after a typhoon – a post-disaster power struggle

A year after typhoon Haiyan hit the Philippines, leaving 6000 dead and 4 million homeless, the arranged marriage between the country and its aid workers is showing signs of strain. The main point of contention: who’s in charge of humanitarian relief? Photographer Pieter van den Boogert and I delved into the workings of the humanitarian aid machine.

This series was made possible in part by grants from the Dutch Foundation for Special Journalism Projects and from the National Postcode Lottery Fund for Journalists, awarded by Free Press Unlimited.