On September 6, 2016, Darren Seals, a Ferguson protester and local activist, was found dead in St. Louis’s Riverview municipality in a car that had been set on fire. He had been shot to death before the car was torched. The crime is being investigated by St. Louis police as a homicide. There have been no arrests. Seals was 29 years old.

Do you know who Darren Seals is? Maybe you do, since his murder quickly became international news, covered by the very media outlets which, in life, he chastised for ignoring him and the other St. Louis protesters whose activity did not stop after the cameras left town.

Did you know who Darren Seals was before he died? If you live in St. Louis, and were involved in the Ferguson protests, you did. On Facebook and on Twitter, Seals had been criticizing the cooption of Ferguson activism since late 2014, detailing an internal division between the Ferguson movement and the national civil rights movement known as Black Lives Matter. At the heart of this division, wrote Seals, was the exploitation of black pain for profit – conducted not only by white media and NGOs, but by out-of-town black elites who seized on Ferguson as a stepping stone to glory.

In a May 24, 2015 post written in his typically blunt style, Seals excoriated what he saw as the hijacking of Ferguson, and the complicity that lies in silence. “BLACK DEATH IS A BUSINESS,” he wrote. “Millions and millions flowing through the hands of these organizations in the name of Mike Brown yet we don’t see any of it coming into our community or being used to help our youth. I’ve been calling out this shit for months […] People see this as an opportunity to not only build a name but make bank at the expense of the lives of people like me.”

This is why you should know Darren Seals, if you didn’t. He was among few writers to clearly call out the division between the activists of the St. Louis region and the broader Black Lives Matter movement. In St. Louis, this division is talked about on the ground but rarely publicly. In the white-dominated mainstream media, where Ferguson is primarily spoken of as a symbol rather than a place where actual people live and suffer and fight, the fractiousness between local and national black movements has gone largely uncovered.

Having abandoned Ferguson as a place while embracing it as a brand, the national media largely focuses on the camera-friendly Black Lives Matter movement, which is how Seals ended up falsely being labeled a member of Black Lives Matter after he was killed.

Darren Seals arriving at Michael Brown’s funeral. Photo by Youth Radio / CC

What Seals fought for

Seals’ forthrightness on the issue was and remains rare. If you are a black U.S. citizen fighting for black rights, you are the underdog – up against a white supremacist system in which brutality toward blacks is legitimized and practiced, especially by police. To expose internal fractures can appear to make the overall movement vulnerable, as it seems to play into the hands of white right-wing movements longing for the black rights movement to collapse. This power imbalance, combined with reluctance to criticize other black activists ostensibly fighting for the same broader goal, has made many who share Seals’ views wary of speaking them for fear of causing offense.

Seals never cared if he offended. His blunt assertions that the movement had been hijacked by out of town activists and NGOs – as well as his misogynist and homophobic comments about other black protesters – offended many.

Many disapproved, but few in the Ferguson movement did not understand the pain behind Seals’ choices – the pain of living in a region overexposed and ignored at the same time

But his views on movement cooption were also embraced by many, particularly as local activists from Baton Rouge, Milwaukee, Baltimore and other cities where mass protests arose in reaction to police brutality began to express the same critiques. This is our city, our struggle, and we already have groups who have been fighting this struggle for years, they noted, balking at the sudden arrival of celebrity activists and NGOs who had ignored their day-to-day plight until the cameras arrived.

Cameras were never Seals’ concern: the streets of St. Louis were. St. Louisans had known Seals since August 9, 2014, the day Mike Brown was killed by Officer Darren Wilson in Ferguson. They knew him for confronting cops like police union official Jeff Roorda, who flaunted his “I Am Darren Wilson” bracelet shortly after Brown’s death, and for condemning the out-of-town protesters who, thanks to media exposure, became the voices of a movement they did not start.

On one infamous occasion in early 2015, Seals slapped DeRay Mckesson, a Minneapolis-based school administrator who arrived in Ferguson over a week after the protests began, but became the face of Ferguson coverage, landing a New York Times Magazine cover applauding his efforts in May 2015. Seals accused Mckesson – who had by then long left St. Louis behind – of hijacking the Ferguson movement and neglecting the cash-strapped local activists still being targeted, jailed, and fined by the police.

After the slap heard around St. Louis, both activists continued to fight for black rights, but in very different ways. Mckesson went on to meet with elites in Aspen and DC and unsuccessfully run for mayor of Baltimore. Seals went back to his job on the General Motors assembly line, and tried to raise money for underprivileged black children in St. Louis.

Many disapproved of Seals’ physical aggression or choice of Mckesson as a target, but few in the Ferguson movement did not understand the pain behind it – the pain of living in a region overexposed and ignored at the same time. The pain of black death turned into a business, as Seals saw it.

A group of demonstrators prepare to protest for another night in Ferguson, Missouri, August 12, 2015. Photo by Lucas Jackson / Reuters

Who Seals was

St. Louis is a sprawling metropolis that feels like a small town because many tend to know someone who has been murdered, or know their relatives or friends. Our connections are solidified in bereavement, and it is painful to write of Darren Seals as yet another name on a long list of people who left us too soon.

Seals was not my friend, but he was an acquaintance. I had met him a few times at protests, we followed each other on Twitter, and we shared close mutual friends. One of those friends is BGyrl, a St. Louis writer who works in the hip-hop industry.

On September 6, I was with my friend Umar Lee, who also covered the protests in Ferguson, when BGyrl sent me a text:

“Someone killed Darren Seals last night,” she wrote. I read the text out loud.

“It’s fucking St. Louis,” Umar said, shaking his head at yet another violent death, another voice silenced, and the horrifying familiarity of it all. Another of my friends, upon hearing about Seals, summed it up: “St. Louis is not where people live, it’s where we wait to die.”

But there was a deeper point in Umar’s simple statement. St. Louis is not a place to be trifled with. If you try to ignore its political reality, and St. Louis will rise up to remind you – with its anger, with its blood, haunting hypocrites like a ghost.

St. Louis was what Darren Seals emphasized, over and over, until the day he died – no matter how badly some wanted him to stop. He documented St. Louis’s hopes and hijacking, along with BGyrl and other black St. Louisans frustrated that a select group of Ferguson protesters – whom BGyrl and Seals called “ACTORvists” – had left St. Louis to travel the country giving talks and working for NGOs and making money, while the vast majority of local protesters were in jail, facing court dates, losing jobs, borderline homeless or actually homeless.

According to Seals, the media bonanza opened the door for others to capitalize on the Ferguson brand – to make “black death a business”

People accused Seals of being jealous, but he was not – he was angry. He wanted a black-run, self-determined movement rooted in local St. Louis concerns. He did not long for validation from white elites. He was furious at the exploitation of his community by outsiders for profit, and fiercely protective of the Brown family.

The Ferguson protests prompted a lot of national talk, but little real local reform. Black residents continue to be killed by police without repercussions, and majority black areas of the region remain disproportionately poor and strapped for resources.

According to Seals, the media bonanza opened the door for others to capitalize on the Ferguson brand – to make “black death a business.” All over the country, organizations held panel discussions on Ferguson. But they rarely included anyone from St Louis, and almost never black men who grew up poor and lacked a college education, despite that it was men like this who stood up to fight for Mike Brown from day one.

And it was in Seals’ arms that Mike Brown’s mother wept.

What Seals claimed

Here we arrive at what Seals was investigating before he died. He, along with me and others in St Louis, had been attempting to follow the Ferguson money trail for years, but we have not yet found clear answers into how or whether funding by outside and local groups was allocated. However, the discrepancy between who is paid to represent Ferguson to the broader public and who lives day-to-day with the problems of Ferguson is readily apparent.

On August 27, MTV convened a typical “Ferguson” panel. It consisted of five black speakers as well as a white woman named Holly Fetter, who was listed as an “ally organizer”. No one who lived in or near Ferguson was invited to speak about Ferguson.

“What is an ‘ally organizer’?” I texted BGyrl.

“Ferguson without Ferguson again,” she texted back – but then we took a closer look.

Fetter works at an organization called Resource Generation, a charity run by young people between ages 18 and 35 – sons and daughters of wealthy families who say they want to use their inheritance for the public good. The organization admits it has never been in contact with Brown’s family, despite raising money in their name, and claims to have given $200,000 to “support frontline organizing efforts in Ferguson, Missouri” between October and December 2014. Resource Generation also claims to have invested over one million dollars in “black-led organizing” over 2015.

The organization admits it has never been in contact with Brown’s family, despite raising money in their name

Baffled by this discrepancy between the charity’s claims and the poverty we see around us every day, BGyrl and I looked at a Resource Generation map showing how their funds are distributed around the country. It turns out that very little had been allocated to St. Louis, one of the alleged targets of funding.

BGyrl posted information about the group on bgyrlforlife, her Facebook page, and on the website Hands Up Don’t Shoot. She also posted a document from a group called ABFE, written in late 2014, claiming that a number of initiatives in St. Louis would be funded to further black rights. Among their promises were economic support for Ferguson protesters, treatment for PTSD, and the launch of St. Louis independent media.

We don’t know where all this money went. What we do know is that if any of these initiatives were funded, there is little evidence of it on the ground. St. Louis activism remains chronically underfunded, resource deprivation in majority black areas is high, and the region’s problems are ignored by the national media until there is a crisis – like, say, the death of Darren Seals.

Ferguson activist Darren Seals, center, awaits the grand jury decision on whether to indict Darren Wilson in the death of Michael Brown. Photo by Robert Cohen / St. Louis Post-Dispatch via AP

What Seals wanted

One of the last things Seals tweeted before he was murdered was a link to a video interview BGyrl did. She was asked to do this interview after posting the documents on the NGOs mentioned above. Seals said it was the “only interview telling the truth about Black Lives Matter and the Ferguson hijacking.”

It is worth watching BGyrl’s interview if you want the other side of the Ferguson story – the St. Louis perspective. It is worth going to Seals’ social media accounts and reading his own words. These words are not always easy to hear. His language was at times homophobic and misogynist; his critiques of other activists were often viewed as mean-spirited and unfair.

But his overall argument – that black communities in St. Louis have been abandoned by a national movement that gained prominence by dropping the Ferguson name – is hard to dispute.

What the murder of Darren Seals clearly shows is that there is no excuse for ignoring the locals whose everyday suffering represents the reality of what happens here. There is no excuse for the apathy toward and abandonment of St Louis’s black community that predated the killing of Brown and continues to this day.

“Sleep is the new woke,” Seals wrote sarcastically before he died, referring to the hypocrisy he saw in Black Lives Matter and other black rights groups. I did not know Seals well, but I know he would have wanted you to read his words. He wanted people to listen.

He wanted people to wake up.

Correction: An earlier version of this article mistakenly placed the "slap heard around St. Louis" in 2016, but as a reader pointed out, the altercation between Darren Seals and DeRay Mckesson took place in early 2015.

More from The Correspondent:

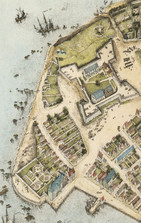

Under Wall Street lies a legacy of slavery. High time for a tour

Since 2009, the Netherlands has celebrated the end of slavery in the Caribbean with an annual day of remembrance. But we rarely hear about the slaves the Dutch kept in the colony that would become New York. I walked around the city to see if I could find traces of this buried past.

Under Wall Street lies a legacy of slavery. High time for a tour

Since 2009, the Netherlands has celebrated the end of slavery in the Caribbean with an annual day of remembrance. But we rarely hear about the slaves the Dutch kept in the colony that would become New York. I walked around the city to see if I could find traces of this buried past.

What I had to tell my daughter about the America of her black classmates

For centuries, black Americans have been systematically brutalized. Now that we have video evidence – going viral – you would expect things to change. But even video cannot open the eyes of those who refuse to see.

What I had to tell my daughter about the America of her black classmates

For centuries, black Americans have been systematically brutalized. Now that we have video evidence – going viral – you would expect things to change. But even video cannot open the eyes of those who refuse to see.

On the ground in Flyover Country

Much of our news comes from the East or the West Coast. But what about that vast space in between, the ‘Flyover Country’? Home to more than half the nation’s people, it is here in the American heartland that presidents are made. Join me in the run-up to the November election, as I report on the U.S. from Middle America.

On the ground in Flyover Country

Much of our news comes from the East or the West Coast. But what about that vast space in between, the ‘Flyover Country’? Home to more than half the nation’s people, it is here in the American heartland that presidents are made. Join me in the run-up to the November election, as I report on the U.S. from Middle America.

Want to read more from The Correspondent?

Sign up for our newsletter and get new ad-free stories every week.

Want to read more from The Correspondent?

Sign up for our newsletter and get new ad-free stories every week.