The Dutch are pretty proud of founding New York. In 2009, the Netherlands and New York celebrated their 400-year history with myriad events, festivals, and parties.

Wherever possible, organizers emphasized shared values like freedom, tolerance, and equal opportunity – values the Netherlands is often given credit for coming up with.

But the story has a dark side that’s often overlooked. In the colony called New Amsterdam, the Dutch kept slaves from day one.

It’s a fact that merits remembering. Each July 1, the Netherlands celebrates Keti Koti, a day honoring the abolition of slavery in the former Caribbean colonies. But what about slavery here, in New York City? Join me on a tour of modern-day New York as I look for traces of the city’s buried past.

Wait – there was slavery in New Netherland?

It’s true that slavery was banned within the borders of the Dutch Republic. But it was common practice from the beginning at the trading post of New Amsterdam, controlled by the Dutch from 1624 to 1664.

A year after the Dutch West India Company established the settlement in 1625, 11 male African slaves (likely from Angola and the Congo) were captured from either a Spanish or Portuguese ship and brought ashore here.

Back in the Netherlands, few people were interested in going to the new colony, with its harsh conditions, to make the land habitable and set up a trading post. So who was going to build the planned fort, the market, the houses, the churches, the hospital, the school? Colonists came to New Netherland from England, France, what is now Belgium, Norway, Ireland, Germany, and other countries, but they were too few in number.

By 1630, there were 100 slaves living in New Amsterdam, making up a third of the population

So the captured slaves, and soon others, were put to work cutting down trees, clearing land, building houses, and laying roads. New Amsterdam’s slaves played a key part in constructing the city wall along present-day Wall Street. Female slaves, brought to the colony a few years later, worked mainly in private households.

The ranks of enslaved people continued to swell. By around 1630, there were 100 slaves living in New Amsterdam, making up a third of the population. In 1664, the arrival of 290 Angolan slaves doubled their numbers; at that point, a quarter of New Amsterdammers were slaves.

In recent years, New York City has made more of an effort to acknowledge this aspect of its past. In the summer of 2015, Mayor Bill De Blasio unveiled a plaque on Wall Street commemorating the slave market that once operated there. The Netherlands, however, isn’t mentioned.

So it’s time to dig deeper. What can the remnants of New Netherland’s history of slavery tell us about our colonial past?

Stop 1 on our tour: The African Burial Ground, final resting place for thousands

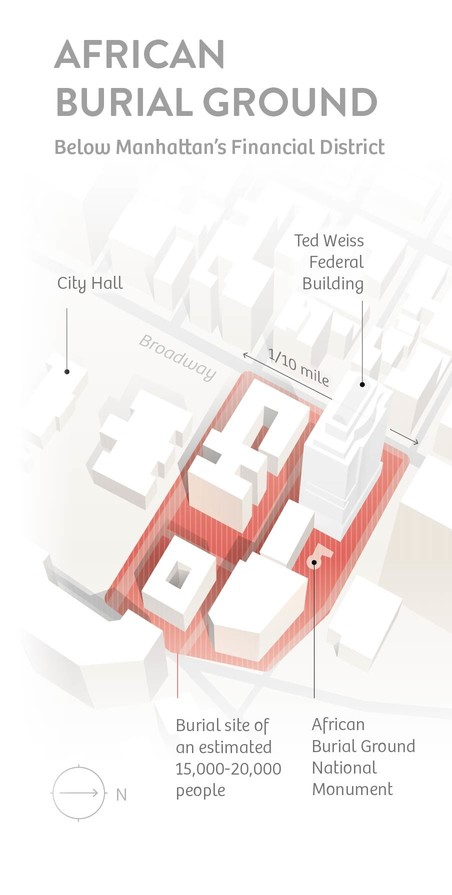

We begin at the African Burial Ground National Monument, in the heart of the financial district. On the corner of Duane and Elk, tucked behind the 34-story Ted Weiss Federal Building, a large granite monument stands in the middle of a tidy lawn.

The memorial pays homage to the 15,000 to 20,000 slaves and free black New Yorkers buried in the 17th and 18th centuries in the area bounded today by Duane Street, Chambers Street, Lafayette Street and Broadway: a cemetery 22 times the size of the lawn I’m standing on.

According to historians, the English founded the Negro Burial Ground – as it’s called on historical maps – in 1690. They did so because free black New Yorkers and slaves weren’t allowed to bury their dead in the city’s main cemetery.

But the English got the land from a Dutch colonist, Sarah Roeloffs. She’d received it as a thank-you gift from Peter Stuyvesant, the director-general of New Netherland, for serving as an interpreter in negotiations with local Indian tribes.

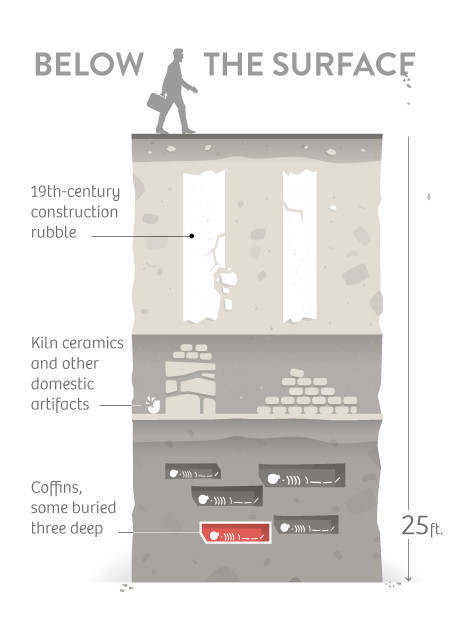

Until recently, the African Burial Ground’s existence was known only to specialist historians. It wasn’t until builders broke ground on the Ted Weiss Federal Building in 1991 and uncovered hundreds of graves that New Yorkers and the rest of the country began to hear about it.

Infographics by Leon de Korte, Editorial Designer at The Correspondent

The discovery made it clear that slavery hadn’t been confined to the southern states but had been entrenched all over the U.S., even in liberal cities like New York. It also showed that enslavement occurred on a large scale, existed from the beginning, and was facilitated by the Dutch.

A sign at the site contains a single reference to slavery’s Dutch origins in New York, stating that Africans were brought to the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam from various regions with different cultures, religions, and languages. A small museum in the federal building has displays on New York’s slaveholding past and the discovery of the burial ground, and a few details on slavery in New Amsterdam.

Stop 2: Greenwich Village, home to numerous slaves

Our search for remnants of New York’s Dutch slaveholding past continues in Greenwich Village. A community of “half-free” slaves of the West India Company made their homes here from 1644. Little is known about where slaves lived before the introduction of “half-freedom.” Various sources say one group occupied a house on Slijcksteeg (Mud Lane), near the modern-day intersection of Broad and Pearl streets.

Slaves had different rights and freedoms in New Amsterdam than they did later under British rule. In the Dutch era, they could marry partners of their choosing, take on paid work in their spare time, sue white colonists, and testify against them in court. Slave children could be baptized until 1655. Slaves were also able to earn their freedom.

In 1644, 11 slaves presented West India Company director Willem Kieft with a petition demanding an end to their bondage. They and their wives were ultimately granted “half-freedom.”

Unlike white colonists, they had to pay an annual tribute to the company, but in return, they and their families were allotted plots of land where they could live independently, cultivate crops, and keep what they grew. They also weren’t required to labor in other colonies. They did, however, have to work for the company on demand, and their children were its property.

Their farms were located in present-day Greenwich Village. By 1664, about 30 free and half-free black landowners and their families were living there.

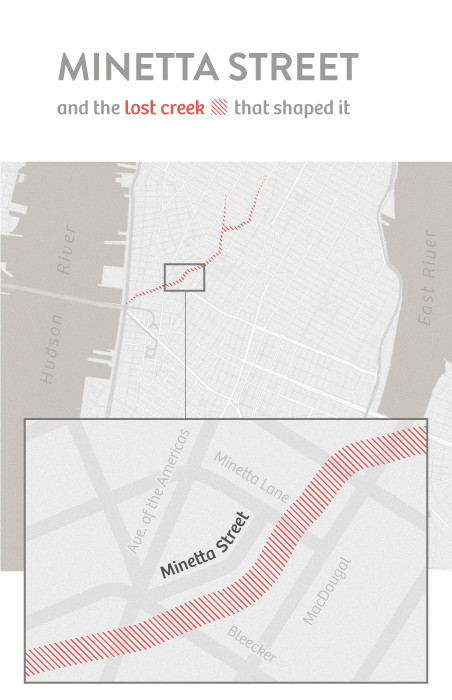

Today, the Village bears few signs of their presence. The most visible is crooked Minetta Street, two blocks from Washington Square Park. Its bend follows the course of an eponymous lost creek that ran past the slaves’ farms.

Infographics by Leon de Korte, Editorial Designer at The Correspondent

Southeast of Greenwich Village lies another district linked to Dutch slaveholding: the Bowery. It was once the farm of New Netherland’s director-general Peter Stuyvesant, who governed New Amsterdam from 1645 to 1664. His land stretched roughly from where East 3rd Street is today to St. Mark’s Church-in-the-Bowery, where Stuyvesant lies buried. After the West India Company itself, he was New Amsterdam’s biggest holder of slaves; he had 10.

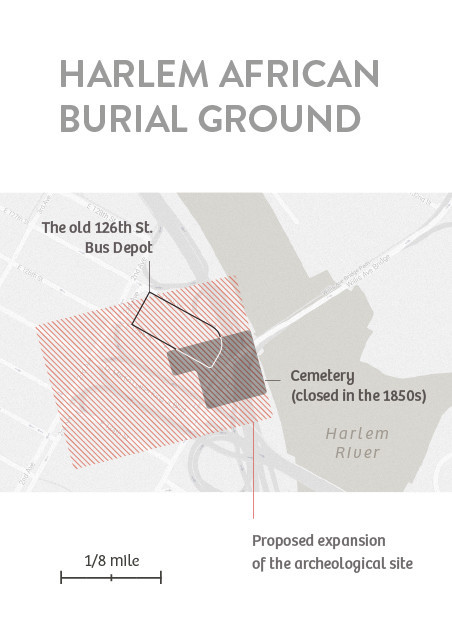

Stop 3: The Harlem African Burial Ground, bearing no trace of its past

We move on to the Harlem African Burial Ground, where free black New Yorkers and slaves were laid to rest until the 1850s. Today, the old 126th St. Bus Depot is all that marks the spot. The cemetery belonged to the Low Dutch Church of Harlem, built by colonists in 1660.

Infographics by Leon de Korte, Editorial Designer at The Correspondent

The first archaeological dig began in summer 2015. Under the depot’s concrete floor, researchers found 140 bones and fragments and one intact skull, likely that of a woman of African descent.

The remains prove that African-Americans made up part of the Harlem community from the beginning. Until recently, their presence in the early years and the part they played in the colonial community were hardly acknowledged. The influx of African-Americans into Harlem in the early 20th century is usually considered the beginning of black influence in the neighborhood.

Walk around the bus depot and you’ll see broken-down cars, garbage, shards of glass. The occasional bus or car goes by. There’s no information board or anything else to indicate the site’s history. The only sign I see is a piece of cardboard held by a man who’s begging from passing drivers.

I wonder how much people around here are concerned about the Harlem African Burial Ground. Most people walking around aboveground probably have other things on their minds. The neighborhood’s long been blighted by acute poverty, drugs, crime, and neglected public housing.

Though Harlem has calmed down in recent years and begun rapidly gentrifying, the run-down tenements, litter-strewn streets, and cheap bodegas remain. I doubt the authorities will sink the same kind of resources into research or memorial-building at this far-flung spot in East Harlem as they did at the African Burial Ground in the heart of the Financial District.

So what about the Netherlands?

Will the Dutch be setting up a museum or memorial site like those at the African Burial Ground anytime soon?

The discussions around what should be done with the Manhattan site in the 1990s were echoed in the Netherlands by calls for more official acknowledgement of slavery. At the time, the issue was a hot topic for debate and activism around the world. Dutch activists frequently made reference to the conversation going on in New York.

In 1993, 130 years after slavery ended in Suriname and the Netherlands Antilles, activists founded the Amsterdam Center for June 30–July 1 (Stichting Amsterdams Centrum 30 juni–1 juli). The organization pushed to get Keti Koti (“Broken Chains”) named a national day of remembrance, now observed each year on July 1.

In 2002, after pressure and campaigning by groups like the National Institute for the Study of Dutch Slavery, a national monument was unveiled in Amsterdam’s Oosterpark.

There are few physical signs in the Netherlands to remind us of the legacy of slavery

And a year later, a museum and research institute designed to raise historical awareness, the National Institute for the Study of Dutch Slavery and its Legacy (NiNsee), opened near the monument. In 2006, slavery was added to the Canon of Dutch History, a guideline list of topics taught in schools in the Netherlands.

Since then, though, little more has been done to focus attention on the nation’s role in slavery. The activists continue to fight, but officials seem disinclined to take much action. Over the past 13 years, NiNsee has been all but obliterated by funding cuts; it lost its building in 2012.

There are few physical signs in the Netherlands to remind us of the legacy of slavery, either. Unlike the U.S., the Netherlands mostly played its part in this chapter of history away from home.

What next?

The Netherlands brought the first slaves to New York. Does that mean it’s responsible for everything that came afterward? And how does the Netherlands fit into the larger landscape of guilt, in other countries where the Dutch traded and owned slaves?

In 1995, at the African Burial Ground in New York, Ghanaian leaders publicly apologized for their country’s role in the slave trade and asked for forgiveness for their ancestors.

Should the Netherlands, too, apologize for all the slaves and free black New Yorkers buried here? And what about the generations of slaves buried in its other former colonies?

These aren’t easy questions to answer, and perhaps the answers won’t be simple. But the Dutch should recognize that our country has left behind a clear legacy of slavery – part of it in New York, that city we so love to brag about.

—Translated from Dutch by Laura Martz and Erica Moore

More from The Correspondent:

Meet Darren Seals. Then tell me black death is not a business

This Ferguson protestor and local activist was found murdered in St. Louis last month. To the end, Darren Seals continued to call out those who exploited black suffering for their own benefit – something that didn’t always win him friends. A portrait of a city’s pain and a life cut short.

Meet Darren Seals. Then tell me black death is not a business

This Ferguson protestor and local activist was found murdered in St. Louis last month. To the end, Darren Seals continued to call out those who exploited black suffering for their own benefit – something that didn’t always win him friends. A portrait of a city’s pain and a life cut short.

How I tried to cover 605 elections in one day

This election year, instead of following the Big Race, I’ve been talking to everyday Americans campaigning to improve their cities and streets. In April, I set out to cover 605 local races and proposition votes in one day – which turned out to be a big race in itself.

How I tried to cover 605 elections in one day

This election year, instead of following the Big Race, I’ve been talking to everyday Americans campaigning to improve their cities and streets. In April, I set out to cover 605 local races and proposition votes in one day – which turned out to be a big race in itself.