“It’s like showing pictures of war victims in a story about peace.”

This is one of the many responses to photos of bonsai trees in an interview with forester and writer Peter Wohlleben. The images are part of The Bonsai Project.

It was my idea to publish those photos with that story. And my choices don’t often generate this kind of response. The main objection voiced in the negative reactions? Bonsai were seen as the ultimate unnatural plant, in an article about leaving nature to nature.

“It’s just like Chinese women, having to force their feet into tiny shoes their whole lives.”

There were loads of relevant remarks from readers. Many revealed an underlying assumption about the role of images in journalism: Namely, that pictures should serve to reinforce the written word.

But is that really the only, or even the main, purpose that photos or illustrations serve?

Sublime nature or bound feet

First, a little more on this particular case: In the introduction to her story, A tree walks into a courtroom, Lynn Berger explains why she wrote the article. The German forester Peter Wohlleben is convinced that we will soon come to see trees in a radically different light. In ten or twenty years, he believes, we will talk about trees the same way we now talk about animals and animal welfare. “We are losing more and more nature,” he warns, “and the nature we still have around is often shaped by human hands. The landscape has lost its soul.” Wohlleben advocates admitting our natural environment to the domain of legal representation – giving trees, rivers, and oceans legal rights.

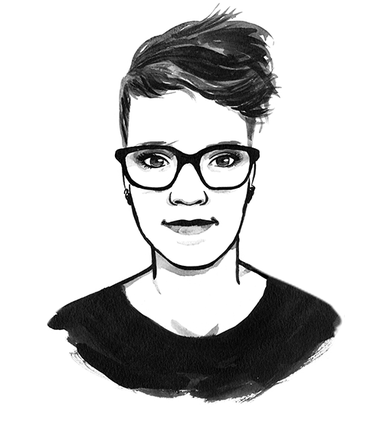

Untitled #1, The Bonsai Project: Typology. © Sjoerd Knibbeler and Rob Wetzer

The photographs from The Bonsai Project were taken by Sjoerd Knibbeler and Rob Wetzer over a period of two years. All over the world, they have photographed bonsai trees – painstakingly created in accordance with traditional practices, and worlds away from the standard mini-ficus you can pick up at IKEA. The aim and wish of the bonsai master is to grow a tree formed to resemble its counterpart in the natural environment – the baobab in South Africa, the sequoia in California, the beech in the Netherlands. It’s sublime nature, according to the photographers.

Both inpretations are valid. To quote Dutch photographer and author Hans Aarsman, “Seeing has to more to do with your brain than your eyes. Seeing is more thinking than looking.” The choices made by the photographer coupled with the eye of the beholder makes every image subjective.

As does the context, which is key. If these bonsai photos were exhibited in a museum, then you might simply admire their sublime beauty. But in a story on the rights of trees, published on a journalism platform, the message you get from the text and the one you get from the images can be experienced as contradictory.

Embracing the cliché

And that fascinates me even more about the reactions: Some readers thought these photos were poorly chosen because they contradicted the story. The pictures were not serving the purpose these readers felt they ought to – that is, reinforcing the written word.

If we follow that reasoning, the story should be accompanied by photos of, for example, a lush forest in the spring. Because “sometimes it’s okay to embrace the cliché,” as one reader put it. Do a Google image search for “forest,” and the supply of this type of photo seems endless.

Google’s algorithm dictates that the woods looks like this:

Each picture is a lovely specimen that completely matches what’s described in the article, and there’s certainly plenty to choose from.

Dissonance works better

Why would I then choose to also use that same type of picture in this piece? Cliché is all well and good, but sometimes dissonance works better.

“Perhaps their beauty is inadvertently interpreted as approval”

Bonsai trees like these are a fascinating phenomenon. It’s beautiful how Knibbeler and Wetzer’s portraits make them appear like planets, floating in space. It is the portraits’ esthetic beauty that makes them clash with Wohlleben’s words. As one member pointed out, “Perhaps their beauty is inadvertantly interpreted as approval.”

In the unexpected, the uncomfortable, and the unknown, lies more to learn and discover about the world. Our own individual truth is but one of many perspectives on reality. Journalism, in word and image, does not exist to confirm our view, but to challenge it – enhancing our understanding of the world in the process.

Visual empathy and more

The topics we must understand today are increasing in size and scope. Here at The Correspondent, we write about inequality, climate change, refugees, the financial crisis – and many other complex issues, some of which only become manifest in their consequences. As such, pictures are often insufficient to represent the entire problem. What will become of us if issues become so abstract that we can no longer envisage them? How will we come to grips with the world?

Untitled #2, The Bonsai Project: Typology. © Sjoerd Knibbeler and Rob Wetzer

At the same time, pictures can elicit thoughts about a subject that aren’t possible in words. Pictures call up other emotions, memories, and associations. It’s what Nicholas Mirzoeff, in his book How to See the World, refers to as “visual activism” – visual empathy and more. Images can help us experience issues more intensely. As a result we may draw other conclusions or change the way we do things.

That can be an added value of pictures in journalism: Not representing a topic, but helping us interpret it. Not supporting an idea, but challenging it. And perhaps starting a discussion, enriching a conversation, and increasing our understanding all the while. It’s this quality of images that I hope will be used more and more in the media. Together with my team at The Correspondent, I strive to make image choices that yield rich, layered journalism productions.

So to answer the quote I opened with with a question of my own: Wouldn’t you be even more convinced of the need for peace if confronted with photos of war victims?

I would like to thank all members (and Instagram followers) for their invaluable contributions, and a special thanks to those who agreed to be cited in this article.

—English translation by Erica Moore and Maria Sherwood-Smith

More from The Correspondent:

Cultivating calm: a design philosophy for the digital age

The online environment in which you are reading is an example of my quest as a designer to compose pitch-perfect platforms for others. The Correspondent is a space where journalists help readers get to grips with the world around us. That inspired me to map out my own design philosophy. My aim? To cultivate calm, so that only the content can drive you to distraction.

Cultivating calm: a design philosophy for the digital age

The online environment in which you are reading is an example of my quest as a designer to compose pitch-perfect platforms for others. The Correspondent is a space where journalists help readers get to grips with the world around us. That inspired me to map out my own design philosophy. My aim? To cultivate calm, so that only the content can drive you to distraction.

Save the refugees, become a banker

What does it take to make the world a better place? An emerging philanthropic movement uses a radical new approach to allocating its resources. What can we learn from these uber-rational doers of good? And what should we be wary of?

Save the refugees, become a banker

What does it take to make the world a better place? An emerging philanthropic movement uses a radical new approach to allocating its resources. What can we learn from these uber-rational doers of good? And what should we be wary of?

A day in the life of a sniper fighting ISIS

In few places has the fighting against the Islamic State been as heavy and sustained as in the Syrian town of Kobani, near the Turkish border. The Kurdish population there slowly but surely took back their streets from the terror organization. Filmmaker Reber Dosky made the trek to Kobani and came back with a unique portrait of a sniper in a battered city.

A day in the life of a sniper fighting ISIS

In few places has the fighting against the Islamic State been as heavy and sustained as in the Syrian town of Kobani, near the Turkish border. The Kurdish population there slowly but surely took back their streets from the terror organization. Filmmaker Reber Dosky made the trek to Kobani and came back with a unique portrait of a sniper in a battered city.