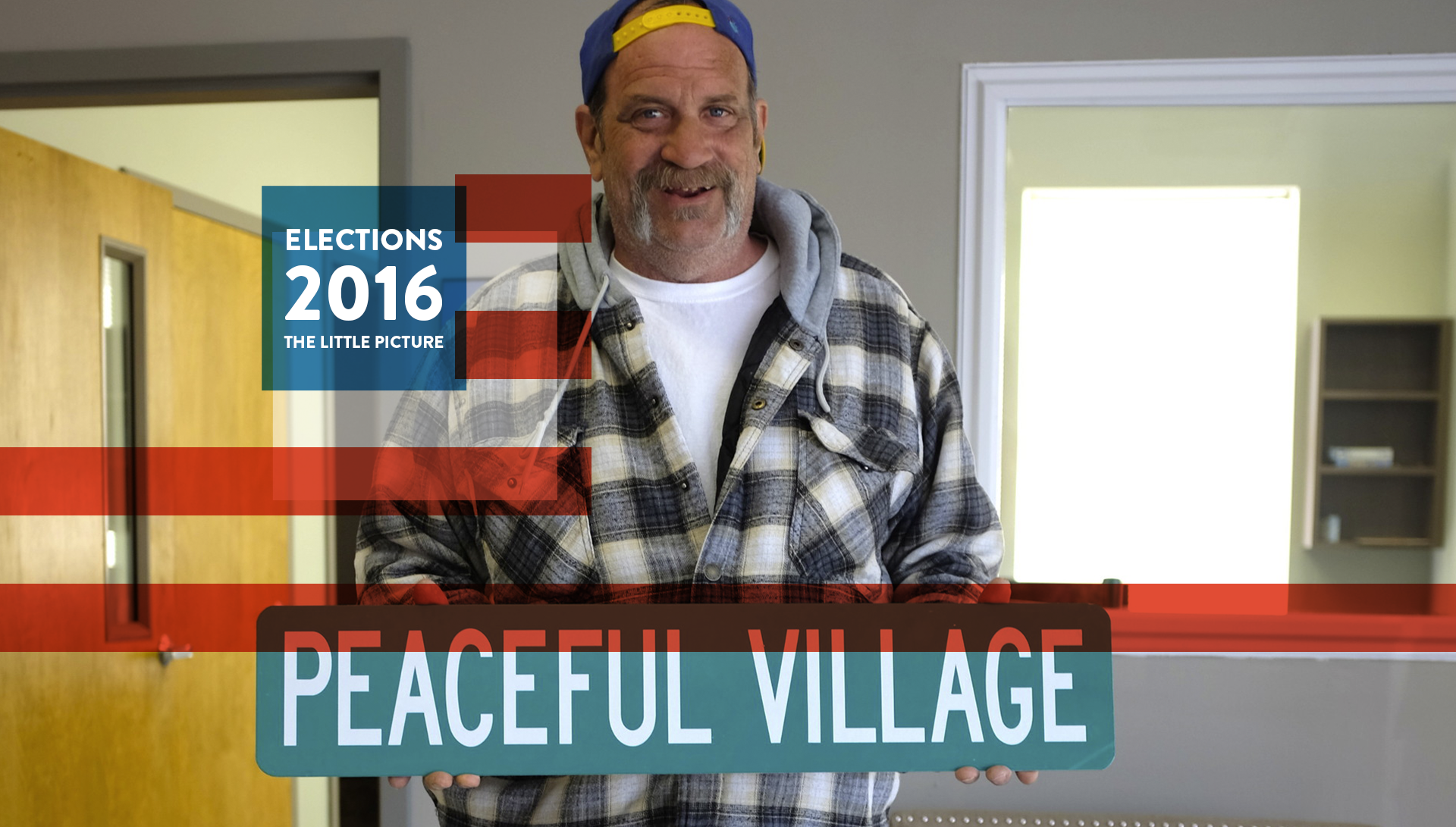

The hamlet of Peaceful Village, Missouri (pop. 9), elected a new mayor this year. There was only one candidate: the current mayor. I called to ask him about his views, but he was too busy to talk. The official election website didn’t tell me much either.

So I drove to the place. It wasn’t as easy as you’d think. Peaceful Village is so small, it’s not even on Google Maps. It does have a Wikipedia page, which lists its coordinates: 38° 28′ 3″ N, 90° 32′ 25″ W.

When I got there, I found myself in rolling green countryside. There were no people, just the warbling of birds. It was peaceful, sure, but it wasn’t Peaceful. When I asked around in a nearby town, nobody’d ever heard of the place. Even the post office didn’t know where it was.

How important can a mayoral election can be in a nine-person town that’s literally not on the map? At best, it would seem of interest as a curiosity.

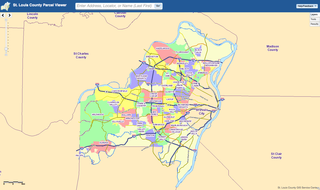

But I want to show you how the system works here in greater St. Louis. It’s one hallmarked by fragmentation. Peaceful Village is part of a near-medieval hodgepodge of about 300 cities, towns, and villages. Together, these tiny kingdoms make up a metropolitan region that’s home to 2.8 million people.

Greater St. Louis comprises hundreds of smaller communities

On Tuesday, April 5, during primary season, this balkanized metropolis went to the polls. Local people voted on a whopping 605 ballot items. I set out to cover as many as I could.

The issues at stake weren’t insignificant. These “little” elections often have a bigger impact on citizens than who gets into the White House. That Tuesday, voters had their say on school boards, alderpersons, mayors, sheriffs, fire departments, judges, sewer investments, storm water operations.

A lot of money was at stake, too. On my street, campaign signs argued for and against scrapping a 1% local earnings tax. This tax, it should be pointed out, brought in at least a third of St. Louis’s budget. Eliminating it could further ruin the city, which is already poor – partly because a third of inhabitants live below the poverty line and therefore pay no tax.

Local billionaire Rex Sinquefield favored scrapping the levy. So he sank $2 million into a campaign fund against it. (Attention, fans of the TV show House of Cards: the character Raymond Tusk, an eccentric birdwatcher and billionaire, is based on Sinquefield.)

They matter, these local elections.

Street signs in Peaceful Village

That’s why I was looking for Peaceful Village. It wasn’t until I walked into a fire station and asked for directions that I made any headway. They said I needed to look for a church called All God’s Children Camp.

The village turned out to consist of a trailer park, a few houses, a ranch, and sure enough, a church, which had been turned into a polling station for the day.

By law, stations must be staffed from 6 a.m. to 7 p.m. – even in places with just nine eligible voters.

A sign on the church door read “VOTE HERE.” Inside, I met Ed, the local landscaper, who’d just finished some mowing. He hadn’t voted; he hadn’t realized there was a mayoral election today. He did know the town was about to get street signs. He was eager to show them to me. If I wanted to find out more about the elections, he told me, I needed to talk to the preacher.

Hunting with guns on the ranch isn’t allowed. Bows and arrows are OK

Peaceful was only eight years old, the preacher told me. It was founded by a pious developer, who also built the church. He wanted to build more, but various regulations got in the way. So he started a town.

It was a town with very few rules, except for an ordinance prohibiting hunting with guns on the ranch. Bows and arrows were OK. And building permits could be obtained in a day. The preacher beamed. “The less government the better.”

A town for every citizen

Peaceful Village, then, was founded out of an aversion to “big government.” In the United States, it’s relatively easy to set up a city or town. This suits the independent national character. If they could, I think every American would live in a town with a population of one, where they could do what they liked.

It has its advantages. In a place with nine residents, there’s no gulf between politicians and citizens. And the country has a town to suit everyone.

I drove on: 604 elections to go. I crisscrossed the patchwork of communities, passing through towns for white people, towns for black people, towns for the rich, towns for the poor, and every imaginable hybrid thereof.

Even factories and companies have their own towns. Take Sauget, Illinois, part of greater St. Louis. There, regulations for business are so lax that the place consists mainly of pollution-belching industrial plants and strip clubs.

Deer trouble in Country Life Acres

My next destination was the leafy Country Life Acres. With 74 inhabitants, it boasts an average annual household income of $200,000, according to Wikipedia.

Country Life Acres turned out to be a gated community – a neighborhood of big houses literally fenced off from the outside world.

The polling place was in the adjacent suburb of Town & Country. It was another wealthy enclave, with pine trees, big houses, tall fences. Porsches were parked outside the polling station.

At the entrance, an alderperson candidate was handing out flyers. I asked her what the key issues were around here. One hot potato: deer were a nuisance in the neighborhood.

Crime in Kinloch

“If only we had problems like that,” they’d undoubtedly say in nearby Kinloch, the next stop on my election trail. This community of a few hundred people was closed off, too – not by fences but by huge potholes, concrete blocks in the street, and piles of apparently randomly dumped trash.

The average household income here is about one-20th that in Country Life Acres; life expectancy, almost 30 years shorter. The biggest problems? Serious crime, corrupt officials, and illegal dumping.

I didn’t see any alderpersons, election posters, or other signs of campaigning. City hall, a ruin, was closed. I did spot some kids sitting on a porch, right beside an illegal dump.

The pros and cons of all those elections

This is one downside of fragmentation: it enables segregation. Some people, however, see that as a plus.

Another disadvantage: these mini-towns are often inefficiently and amateurishly run. As a concerned citizen wrote recently on a local website, “The tyrannical, dysfunctional, corrupt, selfish, incompetent, impotent, wasteful, insolvent municipalities in St. Louis County have to go.”

Some people want all the towns to merge. I doubt there’s much chance of that happening: the rulers of all these little kingdoms have an interest in keeping them around. The irony is that a loathing of government has led to so many mini-governments.

Holding all these elections sounds uber-democratic. But microdemocracy can serve as a tool for maintaining the status quo: divide and rule.

Mini-towns, with populations the size of stamp-collecting clubs, can be rife with conflicts of interest. The mayor’s nephew might be the sheriff, and his wife the judge.

The irony is that a loathing of government has led to so many mini-governments

And there’s little monitoring of power. I didn’t meet a single other member of the media on my trip. You can hardly have a “watchdog of democracy” with people voting on hundreds of items in 100-plus towns in one day – you’d need an army of reporters for that.

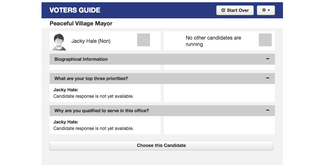

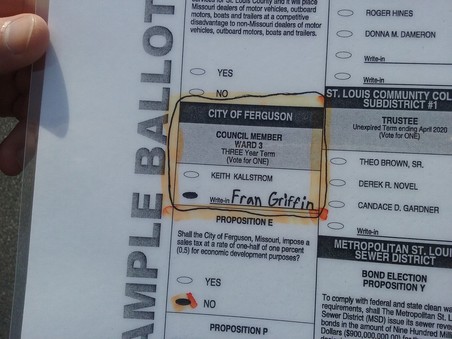

In spite of those 605 ballot items, there wasn’t that much choosing to be done. There were more than 800 candidates running for office. And in countless cases, only one person was running for a particular post. Many votes were effectively reappointments.

That may explain why, although much is at stake, turnout in local races is strikingly low – often just 15%. That’s far less than in presidential elections (about 50%). Local races are much more complicated. Figuring out which district you belong to is like solving a tricky jigsaw puzzle. And it can seem like you need a master’s degree to understand some of the issues. “Vote Yes on Proposition X,” the signs say – that’s a lot less straightforward than Clinton versus Trump.

On top of all that, this election day (as in previous years, by the way), the St. Louis County elections board massively screwed up: it sent the wrong ballots to 60 polling stations, so the few people who showed up couldn’t even vote.

At 7:30 p.m., a judge ruled the polling places could stay open late. But by then, most had already closed.

Democracy’s wrap party

In the evening, I drove to the county elections board office, located on a former industrial site. Volunteers were delivering the ballot boxes from the hundreds of polling places. Democracy’s wrap party was in progress.

The director led me personally to the Tabulation Room, where stressed staff members were counting ballots. There was even a Viewing Room where the press and public could watch them through a window. Other than a lone photographer, I was the only person there.

As I drove home that night, local radio was covering the national elections – the Republican primaries, that is.

The next day, all the results were in for those 605 ballot items. Broadly speaking, things had stayed more or less the same across this city of 2.8 million people.

I tried to call the mayor of Peaceful Village, Missouri, a few more times. He never answered or returned my calls. According to reports, though, he’d been reelected – by a landslide eight of the nine votes.

—English translation by Laura Martz and Erica Moore

More stories from The Correspondent:

What I had to tell my daughter about the America of her black classmates

For centuries, black Americans have been systematically brutalized. Now that we have video evidence – going viral – you would expect things to change. But even video cannot open the eyes of those who refuse to see.

What I had to tell my daughter about the America of her black classmates

For centuries, black Americans have been systematically brutalized. Now that we have video evidence – going viral – you would expect things to change. But even video cannot open the eyes of those who refuse to see.

Nearly all the world’s relief supplies

pass through this desert

In an unlikely spot in the middle of the desert lies the world’s largest stockpile of humanitarian relief supplies. Blankets, tents, buckets, and bodybags await the next big disaster. But why here, in Dubai? And what are conditions like for the city’s migrant workers? A travel log from a surreal place.

Nearly all the world’s relief supplies

pass through this desert

In an unlikely spot in the middle of the desert lies the world’s largest stockpile of humanitarian relief supplies. Blankets, tents, buckets, and bodybags await the next big disaster. But why here, in Dubai? And what are conditions like for the city’s migrant workers? A travel log from a surreal place.

Never before was so much of the world fenced off by barbed wire

Since its invention a century and a half ago, barbed wire has left a trail of blood in its wake. First developed to keep livestock in or out, it was swiftly put to use to divide humanity into the haves and the have nots. If Google Maps were honest, it would show barbed wire everywhere – in combat zones, along national borders, around ranches, schools, and prisons. For my recent book, I took a look at how things got to this point: a brief history of the Devil’s Rope.

Never before was so much of the world fenced off by barbed wire

Since its invention a century and a half ago, barbed wire has left a trail of blood in its wake. First developed to keep livestock in or out, it was swiftly put to use to divide humanity into the haves and the have nots. If Google Maps were honest, it would show barbed wire everywhere – in combat zones, along national borders, around ranches, schools, and prisons. For my recent book, I took a look at how things got to this point: a brief history of the Devil’s Rope.