“Don’t stop covering our stories. Things have changed because of Ebola - there’s so much still to report on.”

This message popped up on my cell on my way home from work one day last fall. The end of the Ebola crisis in West Africa was in sight, but Amjata Bayoh, one of the dozen citizen reporters in Sierra Leone I’d been working with throughout this devastating epidemic, was asking me not to forget him and his country.

I spent the whole evening chatting with him on WhatsApp about how the crisis was still affecting day-to-day life in Sierra Leone: about the collective trauma of communities that had been worst hit, about the ongoing economic effects of market and border closures, about the social impact of the fear and mistrust that had paralyzed the country.

For over a year during the worst of the crisis, all public gatherings were banned. That meant no school, no university, no sporting events, no nightclubs, no markets. People were scared to shake hands or hug each other for fear of infection. There were lockdowns and curfews, and public gatherings could only take place under strict conditions.

So what was left of public life in Sierra Leone?

Filming locations for the documentary shorts, all visited with local reporters.

These reporters see what we cannot

I got to know Bayoh while in Sierra Leone for my work with On Our Radar, an organization that helps people in some of the most remote and marginalized communities report on the world around them. Bayoh is one of the people doing this work, using the tools available – like cell phones, WhatsApp, and videos – to share their stories from their perspective. His message that fall evening inspired a new project: After Ebola.

With the help of a dozen citizen reporters around the country, I wanted to find out what Ebola had changed in their communities and whether life was starting to get back to normal.

I wanted to find out what Ebola had changed in their communities and whether life was starting to get back to normal.

They reported the crisis from places that foreign journalists could not reach – many roads and borders had been closed, and whole regions had been quarantined. Travelling to Ebola hotspots at the peak of the crisis was simply too risky for many journalists.

What kind of impact does an epidemic of this scale have on one of the world’s poorest countries? And what did it mean for Sierra Leone in particular, still recovering from a brutal civil war that ravaged the country between 1991 and 2002?

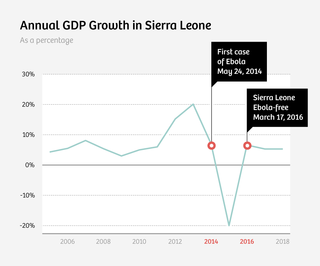

Figures from the World Bank paint a grim picture of Ebola’s devastating impact on Sierra Leone. After more than a decade of consistent year-on-year economic growth since the end of the civil war in 2002, the economy took a sharp downturn during the crisis.

Source: The World Bank

In 2016, things seem to be to picking up again and the World Bank forecasts stable growth of 5 to 7% per year between now and 2018. This is good news, but it’s still a long way from the progress the country had been making before Ebola.

Of course, this epidemic was about so much more than economics. With the After Ebola project, I wanted to dig beneath the surface of the data to investigate the ways the Ebola crisis had changed people’s relationships, their attitudes, their plans for the future.

In the following four stories, the local citizen reporters provide a series of snapshots that reflect Sierra Leoneans’ ongoing battle to rebuild – economically, emotionally, and socially – in the wake of the largest Ebola epidemic in history.

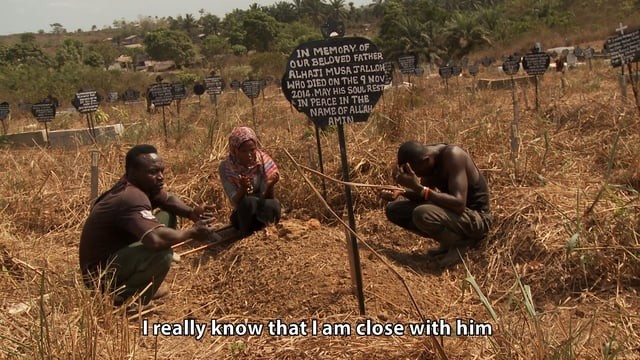

Documentary short 1: Searching for my father’s grave

The Ebola crisis may have come to an end, but the search for those who died continues.

People who contracted Ebola were often rushed to medicals centers far from home for treatment. Hundreds of victims’ families still don’t know where their loved ones are buried.

As numbers fade on poorly marked graves, time is running out for these families who may never locate the burial sites of their loved ones.

Mariama B Jalloh lost her father during the outbreak. In this film, Mariama tells the story of the search for her father’s grave, 18 months after his death.

Searching for my father’s grave. Reporting by Mariama B Jalloh.

Documentary short 2: Why the Sunday market in Koindu is still closed

Many people have returned to work since the end of the crisis, but not everything is up and running yet. Public markets were particularly hard hit by the nationwide ban on public gatherings, and despite protests, the ban on Sunday markets is still in effect.

The problems this has caused are evident in Koindu, a market town in Eastern Sierra Leone close to the Liberian and Guinean borders. Its famous Sunday market – formerly frequented by up to 3,000 buyers and traders – is one of many markets that have yet to re-open.

Theresa Jusu, Chair of the Koindu Association for Market Women, wonders when she and her friends will be able to set up shop again.

Why the Sunday market in Koindu is still closed. Reporting by Moses Kortu.

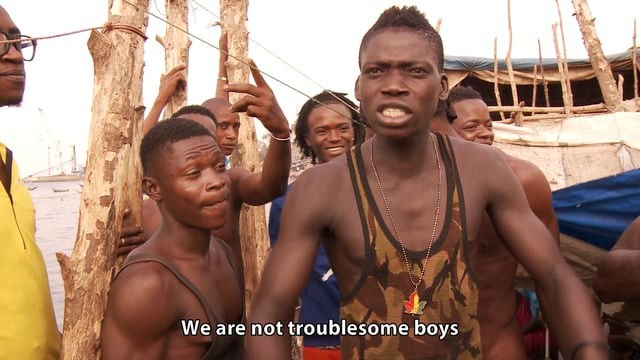

Documentary short 3: Foot soldiers of the fightback

Communities pull together in times of crisis and, for some, the Ebola outbreak was an opportunity to show their worth.

A slum-based gang called the Tripoli boys, previously described by many as “bad boys” in their community, emerged as unlikely heroes during the epidemic.

Moa Wharf slum in Freetown is home to some 8,000 residents who live packed into one square kilometer of shacks straddling open waterways, overflowing with sludge. When the first Ebola case was reported here in April 2015, it had all the makings of an unmitigated disaster.

But instead, this community became a model for an effective Ebola awareness campaign, due in part to the efforts of the Tripoli Boys.

But what are the Tripoli Boys doing now?

Foot soldiers of the fightback. Reporting by Mohamed Kamara and Amjata Bayoh.

Documentary short 4: New beginnings

Despite the collective trauma and the economic hardship, much of Sierra Leone has a renewed spring in its step. Things are happening again. Towns and cities are coming back to life.

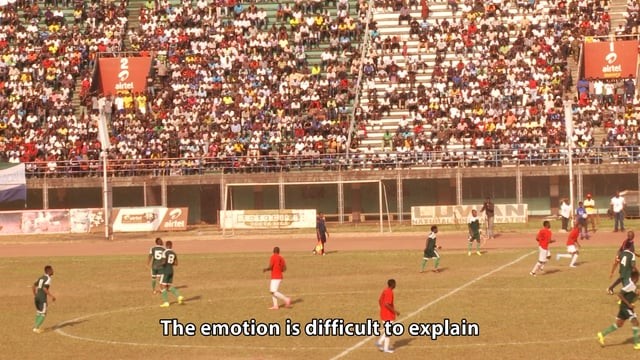

You see it at the Sierra Leone soccer stadium. During the crisis, the stadium had been forced to close its doors, leaving the national team to only play away games. But March 22, 2016, it opened its gates again for a friendly match against Malawi.

Thousands of friends and family members flocked to the stadium for their first match on home turf in nearly two years. The atmosphere in the stadium was one of excitement, emotion, and relief. For many Sierra Leoneans, it seemed things might finally be getting back to normal after two long years.

Football’s coming home. Reporting by Amjata Bayoh.

For the After Ebola project, I traveled to Sierra Leone with Hazel Healy and Laurence Ivil. The trip was part of a larger collaboration between the monthly U.K. news magazine

New Internationalist

and

On Our Radar,

an organization promoting citizen journalism. After Ebola is made possible in part by support from European Journalism Center’s grant program for Innovation in Development Reporting.

Editorial assistance by International Editor Maaike Goslinga. Films edited by Davide Morandini.

More from The Correspondent:

How does a country recover from Ebola? Meet the people rebuilding Sierra Leone

Two years ago, Ebola hit Sierra Leone, only to be pushed from our news by countless other crises. How are the affected communities faring now?

How does a country recover from Ebola? Meet the people rebuilding Sierra Leone

Two years ago, Ebola hit Sierra Leone, only to be pushed from our news by countless other crises. How are the affected communities faring now?

Nearly all the world’s relief supplies

pass through this desert

In an unlikely spot in the middle of the desert lies the world’s largest stockpile of humanitarian relief supplies. Blankets, tents, buckets, and bodybags await the next big disaster. But why here, in Dubai? And what are conditions like for the city’s migrant workers? A travel log from a surreal place.

Nearly all the world’s relief supplies

pass through this desert

In an unlikely spot in the middle of the desert lies the world’s largest stockpile of humanitarian relief supplies. Blankets, tents, buckets, and bodybags await the next big disaster. But why here, in Dubai? And what are conditions like for the city’s migrant workers? A travel log from a surreal place.