It’s New Year’s Eve, an hour past midnight. Kirsten is inside Cologne’s main train station, hemmed in by a big crowd. She’s trying to reach the stairs to the platform, but she can’t move. It’s noisy, and the air stinks of alcohol and sweat.

Kirsten gasps for air. Suddenly she feels a hand sliding across her buttocks, under her skirt. She pushes it away. The building is so crowded, she can’t tell who’s groped her. A few minutes later, the same thing happens again. She feels trapped and powerless.

Meanwhile, Yousef Aljork is standing outside the station, below the iconic clock towers of Cologne’s Gothic cathedral. The square between the station and the cathedral is packed, mostly with young men waving beer bottles. The bang of exploding firecrackers is everywhere.

Aljork sees a group of men surrounding a woman and grabbing her. He’s close enough to hear the men speaking Arabic. He wants to help the woman, but he’s scared.

Our search for the truth

News about the shocking events on New Year’s Eve in Cologne travelled far and wide. In the wake of that night, 1,252 people reported incidents of sexual assault and theft to police. The chief suspects in these crimes? A large group of young refugees.

Nearly four months later, though, confusion still reigns about what exactly happened that night. Who were the perpetrators? What did they do and why? And how did things get so terrifyingly out of hand?

To find out, we – two German journalists, one from Cologne and the other from Berlin – conducted an investigation. In reporting this story, we:

- Analyzed hundreds of media reports, comprising all major regional, national, and international news about the events in Cologne published from New Year’s Eve to the second week of April;

- Read 20 reports and other official documents;

- Interviewed 13 representatives of the authorities;

- Spoke with 14 witnesses;

- Talked to 6 victims; and

- Interviewed 24 additional sources, including experts on refugees and immigration law, asylum seekers themselves, members of the media, and representatives of refugee organizations.

What happened in Cologne

In the first few days after New Year’s Eve, a Thursday, only sporadic reports appeared on the chaos in Cologne. In fact, according to a press release issued by local police on New Year’s Day, the mood the previous night had been “exuberant,” the festivities “largely peaceful.”

That same day, however, posts about sexual assaults in and around the main train station started showing up in Facebook groups. Because of a dearth of further information, only a few local news websites picked up the story.

Four hundred and ninety-two women reported incidents of sexual assault, a category encompassing sexual harassment, assault, and rape.

Then on Monday, January 4, Cologne police chief Wolfgang Alberts announced that crimes of “a completely new dimension” had taken place in the city on New Year’s Eve and that the suspected perpetrators appeared to be Arab or North African. The event immediately hit the front pages of the national and international press.

“1,000 men molest women in Cologne,” the popular German news site Deutsche Wirtschafts Nachrichten proclaimed. Two days later, the front page of Bild, Germany’s number one tabloid, warned of “Sex mobs across Germany.” And daily newspaper Die Welt, citing anonymous police sources, said most suspects were Syrian refugees newly arrived in Germany.

Meanwhile, the number of reported crimes kept rising. On January 2, police had received nearly 30 complaints, according to Süddeutsche Zeitung. Three days later, that number had risen to 90. By the end of the first week in January, the total stood at 121.

Today, we know that 1,168 police reports were filed in Cologne regarding incidents on New Year’s Eve. A total of 492 women reported incidents of sexual assault, a category encompassing sexual harassment, assault, and rape.

The number of rapes reported may increase; 21 is the most recently released figure.

Volunteer Alexander Schoen was there, but didn’t see anything

Mid-January 2016. At the Cologne train station, people are hurrying to and from work. Groups of police officers are patrolling in and around the building, stopping the occasional young man for a passport check.

Most of the sexual assaults and muggings on New Year’s Eve took place here, in the area around the station. This is where we’ll start our search for the truth.

We meet Alexander Schoen, who in October 2015 founded the Hauptbahnhof-Engel (the ‘Train Station Angels’), a group of volunteers who roam the station at night offering free food, drink, and assistance to refugees and others in need. On some nights, he tells us, more than 100 refugees arrive here by train, exhausted from the long journey and often without a follow-up plan.

Schoen was here on New Year’s Eve and spent hours walking around the station with other volunteers. “The station was packed,” he recalls. “A lot of people seemed drunk.” The mood was aggressive and agitated. He saw two women crying at the front desk of the police station inside the building. Schoen emphasizes that he doesn’t want to cast doubt on the victims’ accounts, he just didn’t personally witness any sexual offences or muggings.

Schoen’s recollection raises questions. German Justice Minister Heiko Maas called the events in Cologne “organized crime.” But if this was truly large-scale, organized crime, how could someone who was patrolling the station not have noticed anything?

Witness Yousef Aljork: "Around midnight, things took a turn for the worse"

It’s freezing outside, and icy rain is falling. It’s Saturday, January 16, and about 100 Syrians have gathered on the square in front of Cologne’s train station for a protest called Syrians Against Sexism. They’re holding signs saying “We respect German social values” and handing out flowers to passersby. The group is determined to “show the Germans we’re not bad people,” says Yousef Aljork, a 25-year-old Syrian refugee.

By now, the number of crimes reported to the Cologne police has shot up to 653. We’ve come to the protest hoping to find more people who were here on that infamous night. We’re not the only ones looking to talk to witnesses. Cologne’s public prosecutors have announced a €10,000 reward for tips leading to criminals’ identification or arrest, and the offer has brought numerous people to the square, many of them journalists. Aljork and other refugees are being besieged with requests for interviews.

Aljork, who has a neatly shaved beard and dark, gelled hair, tells us he taught French in Idlib, Syria. When war broke out, he ended up in prison, where he was tortured for 45 days for protesting against president Bashar al-Assad’s regime.

After his release, he departed for Lebanon, leaving behind his parents and eight brothers and sisters. He lived in Beirut for a year, then spent another in Istanbul. In both cities, he barely scraped by. When friends told him he could get housing and language courses in Germany, he wanted to go.

“Some men trapped one or two women between them and started touching them all over. Some of them were stealing money, phones, or other things.”

On New Year’s Eve, Aljork went to central Cologne to take part in the festivities. He arranged to meet his uncle, whom he hadn’t seen since Istanbul. At the station, the two men walked around among the revelers for a while.

Around 11 p.m., Aljork says, the station and the surrounding area became extremely crowded. By then, he and his uncle were standing in the square between the station and the cathedral, hardly able to move. They got separated just before midnight, and since his uncle’s phone battery was dead, they couldn’t contact each other.

“Around midnight, things took a turn for the worse,” Aljork says. “Some men trapped one or two women between them and started touching them all over. Some of them were stealing money, phones, or other things.”

According to Aljork, the perpetrators were organized in groups of approximately 8 to 10 men. He heard some speaking Arabic with a North African accent, and he saw a group of North African men surrounding a woman.

He was afraid to intervene and didn’t dare approach the police out of fear it would affect his application for asylum, which was in process. Aljork wanted to leave, but he stayed put, hoping his uncle would find him. Around 2 a.m., they finally found each other and immediately left – feeling terrible about what they’d just seen.

Victim Kirsten: "I felt something on my buttocks and thought, What’s that?"

Around the same time, Kirsten managed to catch a train out of the packed station. She was relieved to escape, but she didn’t really understand what had just happened to her.

The 22-year-old’s evening had begun at 7:30. She’d arranged to meet her friends at Gaffel am Dom, a popular beer hall in the city’s main square. Just before midnight, they all went outside to watch the fireworks. Right away, she saw that the large crowd was mostly made up of young foreign men who were drunk, yelling and throwing firecrackers. “It was like a war zone,” she says.

Kirsten comes across as a confident woman. She does krav maga, a martial art, every week and is an avid runner. But on New Year’s Eve, trying to get a train home, she felt cornered and helpless. The police had blocked the stairs, leaving her stuck in the middle of a mob.

“First, I felt something on my buttocks, and I thought, What’s that?” she says. “I tried to push it away, and then I realized it was a hand. But it was so crowded, I couldn’t even tell who was touching me. A few minutes later, the same thing happened again, but this time, a hand touched me right on the genitals. It wasn’t accidental. It went under my skirt, and that was deliberate. Somebody really groped me.”

Kirsten tried to move, but she could barely raise her elbows, much less get her phone out of her purse. Around her, young men – according to Kirsten, they looked like “refugees who’d just arrived in Germany” – were giving her “dirty looks that were obviously sexually intended.” Kirsten started sweating profusely. She could see police on the stairs but had no way of reaching them.

“I can’t remember how many times I was touched,” Kirsten says. “I felt a hand between my legs at least four times, but I have no idea who was doing it. Since there was a big clock on the wall, I was able to see exactly how long I was standing there, which was 45 minutes. I was extremely scared and kept telling myself, ‘Keep calm. Don’t cry.’ There was nothing else I could do.”

At last the crowd began to move, and Kirsten was able to make her way to the platform. She took the first train she saw, even though it was going the wrong way. The next day, she went to the police to report what had happened.

The woman we’re calling Kirsten is one of hundreds who reported sexual assaults on New Year’s Eve and early New Year’s Day in Cologne. She prefers not to go public, wishing to put the unpleasant experience behind her. But she wants to share her negative experiences in the hope that it might help prevent such a thing happening again.

Kirsten isn’t the only one. Stefanie Galla, 43, recalls that the area around the station was incredibly crowded that night, mostly with “migrants.” Two men surrounded her and reached into the pockets of her jacket.

Another victim, whose court hearing we attend, testifies under oath that four “foreign-looking men” repeatedly groped her buttocks as she was walking out of the station.

Back at the scene of the crime, we talk to more refugees. Wisam, a 19-year-old Iraqi, says he saw a German woman running towards the police and pointing out two “dark men” who had apparently stolen her wallet. Joud, a 21-year-old Syrian, says she didn’t see anything. But she decided to leave shortly after midnight, because people were throwing firecrackers, and one went off right next to her.

After listening to numerous testimonies, we still aren’t sure exactly what happened. For some people, last New Year’s Eve in Cologne was like any other; for others, the night was unforgettable in the most negative sense. As Kirsten was trapped inside the station, Alexander Schoen was walking around other parts of the building with no trouble. While Yousef Aljork was watching women being surrounded, Joud only saw people partying.

Authorities: Miscommunication between police units caused chaos

The next step in our investigation is lining up all the information issued by the German authorities and the media side by side. We use it to construct a timeline.

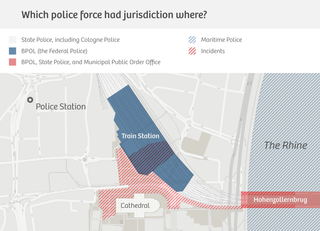

The timeline reveals to us how miscommunication and understaffing by different law enforcement agencies allowed the trouble to escalate.

We also see how different jurisdictions – the State Police of North Rhine-Westphalia are responsible for the city, but the Federal Police (Bundespolizei, or BPOL) are in charge of the train station – created confusion about who was supposed to maintain order in the station and the surrounding area.

The more sources we collect, the more obvious it becomes that a lot of misinformation was spread in the immediate aftermath of New Year’s Eve. First came a Cologne police press release on New Year’s Day suggesting the festivities had proceeded “flawlessly” (which Chief Wolfgang Albers later retracted).

The more sources we collect, the more obvious it becomes that a lot of misinformation was spread in the immediate aftermath of New Year’s Eve.

On January 5, numerous media sources reported 1,000 perpetrators had been involved in the attacks; a police report had previously put the figure at a few dozen. The same day – by which time the incident had become global news – German Justice Minister Heiko Maas described the attacks as “organized crime.” Meanwhile, memes referring to mass assaults on women in Cologne and other German cities were furiously being shared on social media.

Some media outlets framed the incident as a clash between cultures, or as proof that an external force was threatening Western society. The popular magazine Focus put a photo of a naked white woman covered in black handprints on its cover. The quality newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung published an illustration of a black arm reaching up between white female legs. An editorial in Britain’s Telegraph newspaper was headlined “How long before the women of Cologne are advised to stay indoors, or even cover their heads?”

The fallout: an asylum policy overhaul and a chillier climate

Political consequences followed in the form of a tightened asylum policy. German Interior Minister Thomas de Maizière pushed through an existing plan to place Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia on the list of “safe countries of origin,” a legal category that enables swifter deportation of illegal immigrants. He also urged those countries’ governments to take their people back.

In February, the German parliament voted to approve Asylpaket II, a list of changes to asylum law that include quicker deportation of rejected asylum seekers and criminals and two years’ suspension of the right to family reunification for certain refugees.

“Asylpaket II was already in the plans, so it’s not a product of the Cologne incident,” explains Marei Pelzer, a legal policy specialist with Pro Asyl, a German human rights organization focusing on immigration issues. But the political climate after New Year’s Eve did enable the German government to modify Asylpaket II and further restrict asylum policy, she says.

Another expert we spoke to, Stefan Telöken of UN refugee agency UNHCR, says that although Asylpaket II was in the pipeline before January, the section on accelerated deportation is a direct consequence of Cologne. In the new year, Telöken says, the climate for refugees generally became much more hostile.

We are seeing instances of this chillier climate. A swimming pool in Bornheim, a town a few miles south of Cologne, refused entry to a group of 18-year-old male refugees. In Freiburg, a group of clubs and bars stopped allowing refugees in altogether. And sales of nonlethal weapons – mainly pepper spray – shot up, as more Germans apparently felt a need to defend themselves.

Meanwhile, the number of crimes committed against asylum seekers and their homes has been rising. On February 21, a refugee shelter in the town of Bautzen burned down; local residents cheered as the empty building went up in smoke. Two days later, 100 people blocked a bus carrying newly arrived refugees to their accommodation. They harassed those inside, shouting, “Go home!” Four days later, shots were fired at refugee housing in the town of Gräfenhainichen.

The repercussions continue: Cologne’s next festivities in turmoil

“People are starting to hate refugees,” says Mannan, a 20-year-old Syrian who lives in Germany with official refugee status. We meet him at a free dinner being held at a community center in the Ehrenfeld neighborhood. Carnival celebrations are two days away. Dörte Mälzer, one of the dinner’s organizers, announces that the police are taking heavy-handed measures, such as creating a “safe zone” for women, in an effort to prevent sexual assaults and muggings during the festivities.

An Iraqi refugee says he and his friends won’t be taking part in the festivities. “Before you know it, they’ll be calling us criminals.”

A few days before, the German city of Rheinberg decided to call off the carnival parade entirely, fearing misbehavior by men from foreign backgrounds. “It makes you feel bad,” says Mohammed, a refugee we meet at the dinner. “We’re not all bad.” An Iraqi refugee says he and his friends won’t be taking part in the festivities. “Before you know it, they’ll be calling us criminals.”

Kirsten and Yousef Aljork don’t feel like celebrating carnival either. For Kirsten, it’s too soon. Aljork doesn’t want to relive the events of New Year’s Eve.

We decide to go to carnival without them. Right away, we notice that the streets are under heavy surveillance. Around the railway station, the police are out in force. The party proceeds without incident.

How would the news look in light of what we know now?

By March, it becomes clear the German authorities’ investigation will go on for many months to come. We speak with Cologne public prosecutor Ulrich Bremer and ask for an interim update.

We want to know: what would a news report on the events look like if it was written now?

Our news article shows that the great majority of the suspects are of North African origin. When the Cologne story broke just after the new year, this information was unavailable. Did the wrong group get accused of being the probable culprits?

Crime committed by North African migrants, who have little chance of getting a residence permit, is a well-known problem in North Rhine-Westphalia – so well known that three years ago the Cologne police set up a special project to tackle the problem. According to the German weekly magazine Der Spiegel, police in Düsseldorf identified 2,200 active criminals of North African origin in that city.

Most reports, though, have placed the New Year’s Eve events in the context of the recent influx of refugees. The words “Frau Merkel invited me” – uttered by one of the perpetrators, according to a police report – were repeated countless times in the first weeks of January.

How could we all get things so wrong?

Some media outlets defend the way they reported the events. Michael Meier, publisher of the news site Deutsche Wirtschafts Nachrichten, contends that the headline “Spooky: 1,000 men molest women in Cologne, ignoring police” (original German: Gespenstisch: 1.000 Männer belästigen in Köln Frauen, ignorieren Polizei) is accurate and not misleading. He also says the headline covers the information in the original report by Deutsche Presse-Agentur (DPA), Germany’s largest press agency.

Focus magazine says its provocative cover image was only meant to “symbolically represent what happened in Cologne.” Süddeutsche Zeitung apologizes for its heavily criticized illustration.

We contact German Justice Minister Heiko Maas. On January 5, he called the assaults and muggings “organized crime,” but public prosecutor Ulrich Bremer disputed this when we spoke to him. Maas’s press representative, Stephanie Krüger, says the minister didn’t mean organized crime “in the classical sense of the word.”

The bottom line in our reconstruction, though, is that the initial impression of a mob of 1,000 refugees going after the women of Germany never went away. And an entire group of people continues to be associated with crimes it had nothing to do with.

Based on what we know so far, a more accurate description of what happened last New Year’s Eve might be: several dozen young men, many of North African origin, are suspected of sexually assaulting and robbing hundreds of women in the crowd. The crimes were made possible by the crowded New Year’s Eve conditions in and around Cologne’s main train station. They appear to have been further facilitated by poor coordination among the different police forces responsible for responding to the situation.

Public prosecutor Bremer endorses this interpretation. But he adds that the full truth will likely never come to light, in spite of the authorities’ best efforts, owing to a lack of evidence.

One thing is certain: the anti-refugee sentiment seen in Germany after the new year constituted a turning point in the debate. Beneath the surface of German Willkommenskultur, a strong undercurrent of fear and ignorance manifested itself.

How do victims and witnesses look back on that night?

Victim Kirsten says she has nothing against refugees. But the government doesn’t have the situation under control, she says, and the authorities need to create better living conditions for refugees while encouraging them to integrate. “I still feel fear every time I see a young refugee. Not that I’m terrified, but the thoughts are there.”

Aljork says, “I don’t like being in Cologne anymore. I don’t feel comfortable walking down the street."

Aljork says, “I don’t like being in Cologne anymore. I don’t feel comfortable walking down the street."

We go to visit him at his accommodation in the town of Lechenich, 10 miles or so southwest of Cologne, where he shares a room about 100 feet square with two other Syrian refugees. Just after the new year, some local residents visited the center to welcome the asylum seekers and make them feel at home.

They also invited Aljork, who enjoys singing, to join the local choir – a group that’s been around since 1850 and is the pride of the local community.

We go with Aljork to the choir’s weekly rehearsal at the Lechenich community center. Its members – around 25 singers and one female director – greet him with hugs and hearty handshakes. They speak German to him, as he prefers.

We watch Aljork taking part with interest. We see a young man doing his best to learn a new language and make friends with the people around him. We see a refugee being embraced by a new community, in a safe environment.

And when we leave the Lechenich community center later that night and walk back with Aljork, it seems to us that Germany’s Willkommenskultur is not dead after all.

We wrote this story with editorial support from International Editor Maaike Goslinga.

— Translated from Dutch by Laura Martz and Erica Moore, with terminology assistance from Maria Sherwood Smith

Why we’re running stories on Cologne four months after the fact

Today we bring you a story on the shocking New Year’s Eve events in Cologne. Why now? What’s the rationale for a months-long investigation? Editor Karel Smouter briefly explains the idea behind this approach.

Why we’re running stories on Cologne four months after the fact

Today we bring you a story on the shocking New Year’s Eve events in Cologne. Why now? What’s the rationale for a months-long investigation? Editor Karel Smouter briefly explains the idea behind this approach.

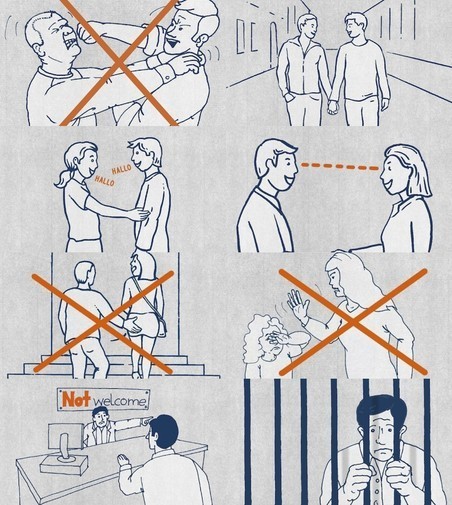

Impressions

The photomontages accompanying this story were made by artist Aram Tanis, whose work questions contemporary visual culture. For the past several months, at The Correspondent’s request, he’s been tracking media coverage of New Year’s Eve and its aftermath, from the night itself and the role of chancellor Angela Merkel to the women’s protests, the impact on carnival festivities, and the leaflets designed to teach refugees about German social norms. He created these montages out of photographs from a broad range of media sources. They are images that have informed our perceptions of the event.

Impressions

The photomontages accompanying this story were made by artist Aram Tanis, whose work questions contemporary visual culture. For the past several months, at The Correspondent’s request, he’s been tracking media coverage of New Year’s Eve and its aftermath, from the night itself and the role of chancellor Angela Merkel to the women’s protests, the impact on carnival festivities, and the leaflets designed to teach refugees about German social norms. He created these montages out of photographs from a broad range of media sources. They are images that have informed our perceptions of the event.