May 2015. An average spring day in southern Thailand. People ride mopeds past the region’s many rubber plantations or lie exhausted in hammocks in front of their homes. Suddenly, three men clad in tattered rags stagger out of the jungle. They are covered in wounds and pale as the dead, and they speak a foreign language.

At first, the villagers think these are the spirits of their dead ancestors, but as more of them follow, the truth slowly dawns on them: these people are still alive.

This isn’t a scene from The Walking Dead, but merely one of the many horrors the Rohingyas endure.

The UN crowned them the world’s most persecuted people back in 2013, and not much has changed since then. In their own country they are imprisoned in ghettos within hostile cities or in camps patrolled by the army – cut off from the outside world.

Outside those walls they are attacked and killed and no one lifts a finger to stop it. Several human rights organizations say that no ethnic group in the world is as seriously threatened by genocide as the Rohingya.

Now that the rainy season has ended, thousands of Rohingyas will repeat the ritual of previous years, taking to the sea in boats that are best described as modern-day slave ships. Like last year, countless Rohingyas will die in the torture camps to which they are taken.

And no, those causing the misery aren’t radical Muslims – they’re nationalist Buddhists. In this story, Muslims are the victims.

The Rohingya have no rights, only restrictions

The Rohingya are a Muslim minority who originate from Bangladesh but have lived for centuries in the Western Burmese province of Rakhine State. Because the government does not recognize them as citizens, but rather as illegal immigrants from neighboring Bangladesh, they enjoy no rights and are subject to restrictions on nearly every aspect of their lives.

In northern Rakhine State, the Rohingya are the majority. Through illegal immigration from Bangladesh and a higher rate of population growth, their number is growing faster than that of the area’s original inhabitants, the Buddhist Rakhine. In recent years nationalist monks and politicians, supported by powerful members of the military, have encouraged increasing distrust of the Rohingya. As a result, more and more people have begun to believe that the Muslim Rohingyas want to take over the area.

In June 2012, clashes between Rohingyas and Buddhists culminated in a bloodbath after three Rohingyas reportedly raped and killed a Buddhist girl. Encouraged by the region’s largest ethnic political party and nationalist monks, and supported by the police and (to a lesser extent) the army, locals burned hundreds of Rohingya homes and killed dozens of people in revenge.

At least 200,000 Rohingyas fled to neighboring Bangladesh, a country even poorer than Burma. More than 140,000 Rohingyas were sent to detention centers in the region, where they survive thanks to international aid. Thousands of others fled to sea in rickety boats, seeking refuge in Malaysia or Indonesia.

A neighborhood as a symbol of determination

Photographer Andreas and I decide to travel to Malaysia to record the stories of displaced Rohingyas and their hardships in the jungle camps. We then travel on to Burma, to see for ourselves why they fled and where the hatred of them comes from. (We explore the latter in a subsequent story.)

The trip takes us to Sittwe, the capital of Rakhine State. Two days after the massacre began there in 2012, one neighborhood was still standing: Aung Mingalar. Thousands of Rohingyas had taken refuge there. They were being protected by the army, which under growing international scrutiny could no longer look away.

Now, more than three years later, the neighborhood is a symbol of determination for those left behind. But life there is hard. Because the residents are neither refugees nor displaced persons, international aid is not allowed. And because no one can freely enter or leave the quarter, there is a glaring lack of almost everything.

Life isn’t much better in Dar Paing, the refugee camp five miles down the road. Photo by Andreas Staahl

The Aung Mingalar quarter in the Western Burmese city of Sittwe. Photo by Andreas Staahl

While fewer than a hundred yards away tourists enjoy fine dining in one of the restaurants along the main avenue, the Rohingyas in Aung Mingalar are gutting their homes in search of firewood for cooking.

Khin Ngunt Nge, one of the quarter’s residents, gives us a despondent look. "When we go outside, we are murdered. Inside, we die from lack of food and medicine. We live like animals in a cage."

On weekends, drunk Rakhines sometimes try to enter the neighborhood to terrorize its residents; rumors that the Rohingyas are planning something regularly make the rounds, drawing troublemakers. The police and the army are supposed to keep the two groups separate, but the quarter’s residents don’t trust them. Out of fear, 70 Rohingyas keep watch every night themselves.

Outside the neighborhood, meanwhile, everything that evokes the Rohingya is slowly disappearing from the streets. The old mosque is abandoned and crumbling; soldiers keep watch to ensure that no one enters the ruin. Pagodas have been built on the foundations of burned-down Rohingya homes, and the Buddhist museum and cultural museum stand on land that was formerly owned by Muslims from the city.

At the Aung Mingalar market in the Western Burmese city of Sittwe. Photo by Andreas Staahl

An Aung Mingalar checkpoint in the Western Burmese city of Sittwe. Photo by Andreas Staahl

U Shwe Hla, the leader of Aung Mingalar, has visible difficulty putting his anger at the encroachment into words. "The government is trying to eradicate us from the gaze of the world because they feel we do not belong here. They say we are Bengali, but we have lived in this country for generations. In the city are mosques that were built in 1726, 1793, and 1859. Back then it was no problem that we lived here; now it is."

He sighs. "We stay here because this is the last place in the city where we still exist, but we live in constant fear. We are protected by the same police who shot at us in 2012. When we are attacked, we have nothing to defend ourselves with."

Nothing less than ethnic cleansing

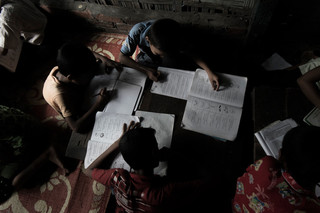

Life isn’t much better in Dar Paing, the refugee camp five miles down the road. Though the roughly 20,000 residents receive aid from international organizations, the standard of living is low. Families sometimes live 40 at a time in small, dilapidated huts. Tuberculosis, dengue fever, and diabetes run rampant. A mobile clinic visits the camp twice a week, but it isn’t enough, say residents.

At the camp’s edge we encounter community leader and former attorney U Kyaw Hla Aung, who was imprisoned for many years for his efforts to achieve human rights and recognition for the Rohingya. We ask him how it is possible that these two peoples are suddenly such mortal enemies.

His answer is clear: the previously moderate mistrust began to grow after influential people intervened. They hoped to improve their political and financial situations.

"I have Buddhist friends in Sittwe, like other Rohingyas here. They also protected us when our homes were attacked. But the government wanted us gone and was too strong. It spread lies about us and paid people from the outside to drive us out. It’s a political issue," he says.

Rohingya children on the Beydar beach at the edge of the Dar Paing refugee camp. Photo by Andreas Staahl

In the Dar Paing refugee camp. Photo by Andreas Staahl

According to U Kyaw Hla Aung, the means the government uses are nothing less than ethnic cleansing. He lists the rumors that are frequently heard but often unconfirmed in Dar Paing:

- Rohingyas die in the hospital after the forced injection of an unknown substance.

- Rohingyas are murdered and the deaths are not investigated.

- Soldiers search Rohingya homes to confiscate anything that might be used as a weapon, down to cooking knives and water pumps.

"We’re afraid they want to disarm us because they are preparing to attack," he says.

In Maungdauw, Rohingyas may not even use the telephone because the police are scared they will contact Al-Qaida. He himself was arrested after the riots in 2012, ostensibly because the police found a letter in his house written in Burmese that said he had joined Al-Qaida.

"In Burmese!" he says, shaking his head. "The government’s lies are sometimes so bad I have to laugh."

A mother with her two children in Aung Mingalar. Photo by Andreas Staahl

The children living in Aung Mingalar have limited opportunities to attend school. Photo by Andreas Staahl

But the effect of those rumors is far from amusing. Mistrust is growing among an influential group of Buddhists, and is so great that he would like to see the UN set up a security zone to protect the Rohingya.

"If the army allows the Rakhine to come here, we are powerless. They will shoot at us and set everything on fire. That danger is immense, and everyone is afraid of it. I’m afraid they won’t stop until everyone is gone."

His daughter has fled to Singapore, where she now works as an assistant professor. She begs her father to leave, too, but he is determined not to let his people down. To underscore his commitment, he is building a new house on the camp’s outskirts.

"I’m building this house because I want to show that we must stay,” U Kyaw Hla Aung says. “This is our homeland; we belong here. If we leave, we give up all that we have."

More and more Rohingyas are fleeing the country

But his message is increasingly falling on deaf ears. More and more Rohingyas want to escape the impoverished conditions in Dar Paing.

On the Beydar beach, adjacent to the camp, the same fishing boats that display their catch on the beach ferry Rohingyas to the larger boats owned by smugglers who will take them to Malaysia, Indonesia, or Thailand.

Beydar beach, adjacent to the Dar Paing refugee camp. Photo by Andreas Staahl

On the Beydar beach, adjacent to the camp, fishing boats bring their catch ashore. Photo by Andreas Staahl

Last year more than 88,000 Rohingyas and migrants from nearby Bangladesh ventured the crossing. Hundreds of people died at sea, and an unknown number more perished in camps set up by smugglers deep in the jungles of Thailand and Malaysia. The survivors were only freed after their families paid hundreds of dollars.

The discovery of dozens of mass graves in May led to a storm of criticism from the international community. Bullet shells, torture devices, and bone fragments bore silent witness to what must have happened there.

All the while the Burmese government denies any involvement in the atrocities. According to government officials, the victims are not Rohingyas but refugees from Bangladesh. However, the residents of Dar Paing assert that when the rainy season ends, thousands of Rohingyas will again depart Burma.

"We run because we know the situation will not change here," says Riyazul Alam, a muscular young man with a fierce look in his eyes. His sister and her son died a few months earlier during their flight when they were beaten to death by other passengers during an argument. Two of her children have been missing since the tragedy, but that does not stop him from leaving as well.

"I know it’s dangerous at sea, but think of my future. We live here thanks to help from abroad, but how long will that continue? Who will protect us if we are attacked? How can my children grow up here? The government raped our sisters and mothers before our eyes, but we could do nothing. I have no future here. My future lies on the other side of the ocean."

Torture camps in Thailand

Seventeen-year-old Diaburahamam survived the boat trip and the jungle camps. We speak with him in a tea house in Alor Setar, Malaysia. He is illegal, which means he still has no rights, and he is traumatized by his experiences.

After listening to the horrors he has endured, I ask him if he regrets leaving.

He shakes his head. "Did I have a choice?" he asks, subdued. He stares at the ground with dull eyes. It is the characteristic look of the child who will never be a child again, the look I also saw in South Sudanese child soldiers and young Yazidis in Iraq.

Scene by scene, he strings together the most harrowing stories, with a monotonous, almost cracking voice. How he was tortured by soldiers in Burma because he had caught a fish where that was not permitted. And how they threatened to kill him if he did not leave.

Photo by Andreas Staahl

"I know it’s dangerous at sea, but think of my future. We live here thanks to help from abroad, but how long will that continue?" Photo by Andreas Staahl

Next came a hellish journey on the water. To carry as many people as possible at one time, the ship had been converted into a sluggish and unseaworthy monstrosity. The more than 500 passengers were so tightly packed that it was impossible to even sit down.

When after a few days the fuel ran out, the ship bobbed adrift on the ocean for five weeks. People fought over food and water to survive. Those who begged for help were beaten to death and thrown overboard by the smugglers.

They arrived in Thailand exhausted and depleted. There the smugglers shepherded them into the jungle. After walking for two days they arrived at a camp of tents made from sheets of plastic. Ten people sat beneath the tarps. When he took a closer look, he saw that three of them were dead, and the others were so emaciated they could barely speak. The prolonged walking gave people injuries that became infected; others suffered from infections encouraged by the permanently wet ground. People slowly wasted away, he says. Pregnant women gave birth in the jungle; he saw several women have miscarriages.

Diaburahamam was tortured and forced to demand that his family pay the equivalent of 1800 dollars as quickly as possible. After a week, his father was able to scrape the money together. The whole village contributed, he says.

"I’m free now," Diaburahamam says, "but I still don’t have any rights. My goal is to travel on to a country where I will have rights."

A resting place for the anonymous dead

In a bumpy clearing in nearby Kampung Tualan lie the graves of 105 Rohingyas who did not survive the jungle camps. The gravestones bear no names, only numbers. The bodies were unidentifiable when the Malaysian police unearthed them from a mass grave in the border area between Thailand and Malaysia last May.

In a bumpy clearing in nearby Kampung Tualan lie the graves of 105 Rohingyas who did not survive the jungle camps. Photo by Andreas Staahl

The gravestones bear no names, only numbers. Photo by Andreas Staahl

We stand beside the gravestones with Mohamed Noor, president of the local branch of the Rohingya Society Malaysia (RSM). "These people fled their homeland because it is unlivable for them there," he says. "They had no other choice."

In August Noor accompanied the remains to their final resting place and led a service for the anonymous dead. He and the mourners prayed to God, "If these people have children or family, please protect them."

New graves have been dug at the edge of the cemetery, because Noor knows that in the coming weeks new boats will depart and new bodies will follow.

He sighs, then says what countless Rohingyas have impressed upon us. "I want the world to know what we’re going through. No people in the world should have to experience this. We are attacked because we’re not supposed to exist."

This article was made possible the Dutch Fund for Special Journalism Projects ( Fonds Bijzondere Journalistieke Projecten, or FBJP )

English translation by Grayson Morris and Erica Moore

More from The Correspondent