Barbed wire is one of the most important inventions of modern times.

I discovered this by accident. It struck me while watching television how often barbed wire appeared in news reports about crisis zones. You couldn’t escape it: there it was, in every war and every demonstration. Wherever migrants or suspected terrorists surfaced, they were held behind barbed wire.

When I decided to examine the history of barbed wire in more detail, I found out that’s how it’s been since the beginning. Barbed wire has always been used to separate living beings, first animals and later people. It’s what tamed the Wild West. It then entered the world stage with a grisly role in World War I. It came to symbolize totalitarianism, thanks to Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin. And today, it serves as an instrument of economic apartheid, by separating human beings into those who may enter and those stuck outside.

For my book on the history of barbed wire, I travelled to the U.S., Bangladesh, South Africa, Belgium, Spain, and Morocco. I also cycled through my own country of the Netherlands and found that barbed wire is never far away. We just don’t notice it anymore. We’re as conditioned as cows; we look right through it.

Barbed wire’s humble beginnings

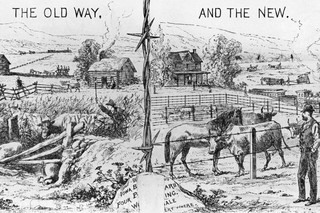

Barbed wire could only have been invented in the United States. Nowhere else was the need for a cheap fencing material so immense and compelling. The migration of settlers to the West stagnated in the mid-nineteenth century. The main reason for this was as trivial as it was fundamental: many aspiring farmers were not willing to try their luck as long as they had no idea how they could fence off their land to protect their crops.

All the natural aids that farmers had traditionally used for fencing, such as stones and wood, were lacking on the prairies of the Midwest. Without fencing, the fruit of their labors was under constant threat. Any passing herd of cattle or buffalo could simply trample the growing grain or gobble it up.

From 1870 to 1878, newspapers and magazines in the Midwest devoted more attention to the thorny topic of fencing than any other political, economic, or social issue. That’s revealing. The American Civil War had just ended, and the country was engulfed in a major financial crisis. But all that was irrelevant to those yearning for affordable fencing. For these farmers, the invention of barbed wire was like manna from heaven. By 1873, people had been hoping and praying for just such a miracle for some time.

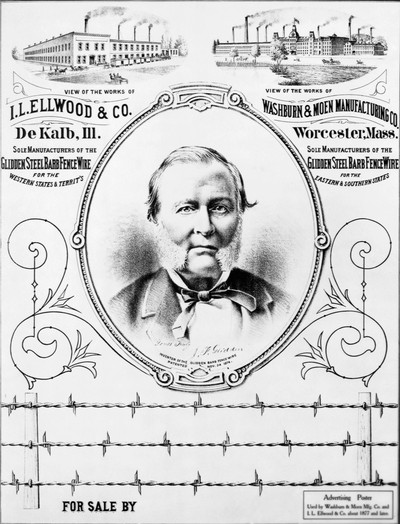

“Joe, these cows in my garden are driving me crazy. They’re eating all the flowers. Could you please do something about it?” Lucinda’s cry for help is in all likelihood where this story began. “Of course, Lucy my love, I’ll deal with it.” How this miracle came about is a story that spiritual father Joseph Glidden and his wife Lucinda would recount to journalists later. Glidden was a farmer from DeKalb, a small town with a thousand inhabitants in the Mississippi Valley 60 miles west of Chicago.

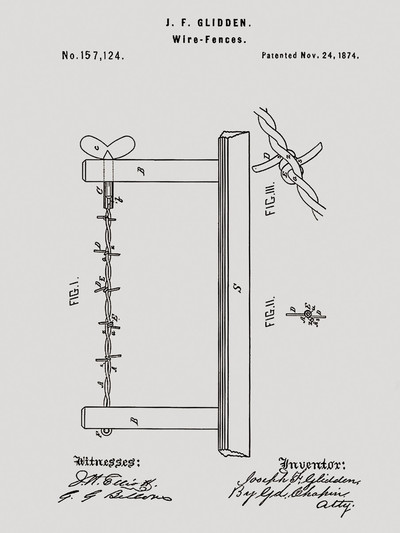

He bought a reel of fence wire at the local hardware store. And as the days began to get shorter, he could be found working in the kitchen in the evenings. His only tools were a pair of pliers, a set of pincers, and different kinds of hammers.

That fall, Lucinda’s wire hairpins started to disappear. One evening, Lucinda was surprised to see her husband fish two of her hairpins out of his shirt pocket. “What are you doing with my hairpins?” she asked. “I’m working on an idea for a fence,” he is said to have answered.

With a pair of pliers he twisted the hairpins one by one into spirals with sharp points. Apparently he later used a coffee grinder to make barbs out of wire. He would then attach strands of barbs onto the wire.

There was one annoyance: the barbs wouldn’t stay in place. Glidden eventually managed to fasten the barbs securely by twisting a second wire around the first. While he wasn’t the first to develop barbed fencing, it was this double-wire discovery of Glidden’s that made him go down in history as the inventor of barbed wire.

Barbed wire’s sweeping impact

The product was a cash cow from day one. It seemed inconceivable, ten years after it was invented, that the United States had ever managed without it. It was light and cheap, and easy to install and maintain. The demand was so overwhelming, and the business grew so explosively, that in 1884 the weekly newspaper The Prairie Farmer devoted a special issue to the phenomenon that “has no equal in the history of industry.”

Barbed wire was the internet of the late-nineteenth century. Everyone had to have it, and have it now.

“Few names are as widely known as that of Joseph F. Glidden,” The Prairie Farmer reported. “Not only has he established a mammoth industry, he has also radically changed the global economy. Thanks to his ingenuity and persistence, fencing has become a piece of cake on this rural continent: simple and affordable. He didn’t accomplish this on his own. But he did lay the foundations.”

With the force of a tornado, barbed wire cleared the way for the final stages of settling the West. Settlers rushed it in its wake. "More white settlers moved further westward in the eight years after affordable material for fencing was introduced than in the 50 years prior to that,” noted the Texan historian Roy D. Holt. At the end of the nineteenth century, 17 million people lived in the West. That was 25 times more than just 60 years before.

Fencing off the wide-open spaces of the American West may have been inevitable, it initially met with great resistance. Barbed wire provided farmers and some cattle ranchers with unprecedented opportunities. But at the same time, it threatened the very livelihood of others, including Plains Indian tribes and small-scale ranchers, who had never had to own land to raise livestock. In some states – Texas in particular – this resistance led to bitter Fence-Cutting Wars.

But as controversial as the Devil’s Rope was, by 1900 the open range was largely a thing of the past, and the cowboy on his way to becoming a tall tale. Barbed wire fencing had prevailed.

And barbed wire prevailed wherever it was introduced. Barbed wire was the internet of the late-nineteenth century. Everyone had to have it, and have it now. Within a quarter of a century, it had found its way to other continents, to all the other areas that needed fencing in order to develop. It reached the Pampas of Argentina, the veldts of South Africa, and the steppes of Australia.

Photo by Hollandse Hoogte

Military use

Army commanders discovered the benefits of barbed wire too. You could use it to hold up an advancing enemy. You could imprison a hostile population on a piece of land with it. That happened on a large scale for the first time during the Second Boer War (1899-1902), the struggle between the British colonial power and two poor Boer republics in southern Africa, the Orange Free State and the Transvaal Republic. When those young nations began to engage in guerilla warfare, the British army restricted the Boer commandos’ freedom of movement by building a barbed-wire fence more than 3,500 miles long. And Boer women and children were imprisoned in concentration camps in Transvaal surrounded by barbed wire.

A Mud Hall Prison, where British Officer Prisoners were kept, South Africa, 1900. Photo by Getty Images

During World War I, a barbed-wire fence cut off Belgium from the Netherlands for three years. Belgium was occupied by the Germans, while the Netherlands was neutral. The Germans wanted to prevent, at all costs, Belgian volunteer soldiers from joining the allied troops via the Netherlands. They even charged the 206-mile-long fence with electricity. From August 1915 onwards, an electric screen separated the two neighboring countries, from the town of Vaals, near Aachen, Germany, all the way to the sea on the western coast. Border residents called it the dodendraad, or "wire of death."

One of the victims was 25-year-old Henricus Lenders from Turnhout, a town about 30 miles east of Antwerp. “The thread of my life,” read his in memoriam card, “has been severed faster than a weaver can weave. My days have gone up in smoke like a thunderbolt. Beloved wife and dearest children, it was for you that I toiled, and it was my love for you that made me fear no danger. In the darkness of night I set off to foreign parts, never for you to see me again.”

Soldiers make their way across a series of barbed wire defenses in WWI, c. 1915. Photo by Getty Images

How many died along the border is difficult to ascertain. Belgian geography professor Dominique Vanneste, who conducted extensive archival research, estimates 800 casualties. Of the dead whose full names are known, three quarters died by electrocution, one fifth during exchanges of fire, while the cause of death is unknown for the remaining casualties. The total number of victims in three years is estimated to be approximately 2000. By comparison, in 28 years 136 people died along the Berlin Wall.

But barbed wire really took off during World War I, when trenches, barbed-wire barriers, and machine guns created impenetrable frontlines. It’s the only major war where barbed wire played a leading part from beginning to end. Without barbed wire, the war never would have dragged on so long. Without barbed wire, the war would never have claimed so many lives.

These are the opening lines of the poem “Naked Warriors” by British poet Herbert Read:

A man of mine

lies on the wire.

It is death to fetch his soulless corpse.

A man of mine

lies on the wire.

And he will rot

Nonetheless, barbed wire only became the symbol of totalitarianism and human atrocity in World War II, as a result of its widespread use in a “monstrous web of slave camps,” as Italian writer Primo Levi described the Nazi system. The eight extermination camps still obscure the fact that there were 42,000 other camps: labor camps, prisoner of war camps and concentration camps. They all had one thing in common: barbed wire.

Barbed wire today

It was also barbed wire that divided Europe into capitalist Western Europe and socialist Eastern Europe for almost half a century. An Iron Curtain was draped over the continent, from Norway in the North to Turkey in the South. As late as the summer of 1989, future chancellor Gerhard Schröder proclaimed: “One should not lie to the new generation after 40 years of West Germany about the chance for German unification: it does not exist.”

When the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, it briefly seemed like barbed wire’s triumphant march would come to a halt. Weren’t walls and fences and all those other barriers absurd and outmoded in a globalizing world?

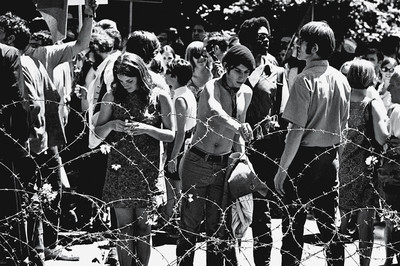

But since the terrorist attacks of 9/11, barbed wire has launched another offensive. It shines menacingly on border fences and border walls that serve to separate wealthy countries from poorer neighbors. It adorns gated communities where the well-to-do barricade themselves in countries where inequality is greatest. It meets a growing demand for security in a world of chaos.

Demonstrators place flowers on a barbed wire fence in People’s Park on the campus of the University of Berkeley, 1969. Photo by David Fenton/Getty Images

If Google Earth could look back in time, to 1874, the year that barbed wire was invented, and then visualize the spread of modern types of fencing, not only barbed-wire fences, but also newer versions, such as wire mesh and other increasingly clever fences, what would we see?

We would be shocked at how quickly barbed wire managed to fill large patches of the map in a quarter of a century. And that was just the beginning. Soon barbed wire and other types of fencing reached the cities. Authorities used them to separate functions: to set off schools from neighborhoods, public gardens from streets. Businesses and citizens protected their valuable possessions behind them.

Nelson Rockefeller and his wife view sights on the east side of the Berlin Wall as pointed out by a West German guide. Photo by Hollandse Hoogte

Since 1870 the world population has quintupled to more than 7 billion people. The number of people that live in cities has increased from 10% to more than 50%. The purchasing power of the average world citizen has increased by a factor of 36. The unbridled growth of fencing was a side effect. Wherever you looked, barbed wire was thriving.

If Google Earth were to show all of this fencing, then we would see a world of labyrinths. Never before has so much of the earth been closed off. Never before has such a large portion of the globe been so compartmentalized.

Today, China and India dominate the global barbed-wire market – good for an estimated 500,000 tons of the stuff a year. That’s some 5 million miles of barbed wire, enough to circle the earth 200 times. That places still exist in our world where there’s no barbed wire is nothing short of a miracle.

English translation by Mark Speer and Erica Moore

Barbed Wire, a History of Good and Evil

This brief history of barbed wire is part of my book on the Devil's Rope, published in the fall of 2015 (in Dutch only).

Barbed Wire, a History of Good and Evil

This brief history of barbed wire is part of my book on the Devil's Rope, published in the fall of 2015 (in Dutch only).

Think land grabbing is a thing of the past? Think again

More than a year ago, Luke Dale-Harris stumbled upon a mystery: Romanian farmers discovered their land had been sold without their knowledge or consent. Together with investigative journalist Sorin Semeniuc, he followed the money trail all the way to Rabobank, a Dutch banking giant that turns out to have invested millions in agricultural land in the country. How did Rabobank come to own stolen farmland?

Think land grabbing is a thing of the past? Think again

More than a year ago, Luke Dale-Harris stumbled upon a mystery: Romanian farmers discovered their land had been sold without their knowledge or consent. Together with investigative journalist Sorin Semeniuc, he followed the money trail all the way to Rabobank, a Dutch banking giant that turns out to have invested millions in agricultural land in the country. How did Rabobank come to own stolen farmland?

The Return of the Wall

Never before have we built as many walls along national borders as in the past 15 years. Official reason? The threat of terrorism. But in practice, walls serve to keep out ordinary people looking for a better life. I tried to uncover the reasoning behind the trend of the 21st century: constructing border walls.

The Return of the Wall

Never before have we built as many walls along national borders as in the past 15 years. Official reason? The threat of terrorism. But in practice, walls serve to keep out ordinary people looking for a better life. I tried to uncover the reasoning behind the trend of the 21st century: constructing border walls.