Prologue

Elsje Schimmel sits at the dining room table. Her older son, Olivier de Bruijn, crouches beside her. His younger brother, Lodewijk, is filming the scene on his phone.

Just days after their father’s sudden death, the brothers are alone with their mother in the house where they grew up. They’re recording the conversation because this might be their last chance to get their mother’s answers to some pressing questions. Elsje Schimmel, 62 at the time of filming, is suffering from a severe form of Alzheimer’s.

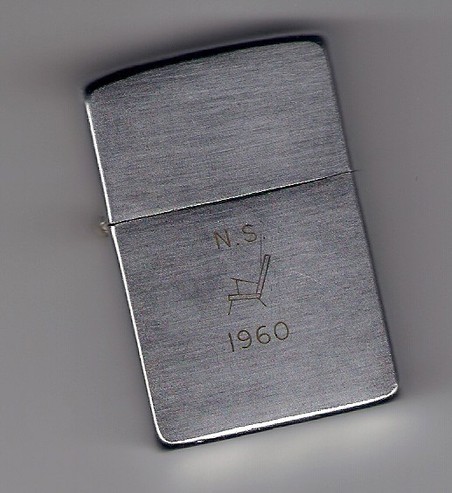

Going through things at their parents’ house, Olivier and Lodewijk came across something odd: an old envelope containing three typewritten pages and a cigarette lighter. Olivier shows the lighter to his mother. A classic Zippo, it’s engraved with an armchair and the initials N.S. Their grandfather’s name was Nico Schimmel.

“Did Grandpa work for the CIA?” Olivier says.

“Yes,” Elsje replies. Gazing vacantly into space, she mumbles something unintelligible.

Olivier calmly continues his questioning, one hand resting gently on his mother’s back.

“Did anyone ever use to come visit you?”

“Yes.”

“Who?”

“The man...” Elsje is having trouble finding the words. She takes the Zippo from her son and plays with it for a minute.

“What did the man do?” Olivier says.

Elsje’s reply is unintelligible.

“Did he bring money?"

“No.”

"Did he come to talk?”

“Yes. To talk.”

“Who did he talk to? Your mother?”

“No.”

“Your father?"

“Maybe.”

Illustration by Lennard Kok

Olivier picks up the typed pages he and his brother found. He leafs through them until he comes to a name. “Did Mr. Prins ever come by?”

“Yes,” Elsje says. “He was important.”

Silence.

“He was nice.”

Olivier shows his mother the pages and asks, “Do you remember this letter?”

“Yes.”

“Did anybody from the CIA ever come to your house?”

“I don’t know.”

“How about Mr. Einthoven?”

“Yes.” His mother looks questioningly at him.

“And Mr. Van Dijk?”

“He’s – he’s the big man.”

“The boss?”

“Yes.”

Olivier is doubtful. He needs to know how much of the letter is true, how much his mother remembers – if she remembers anything at all. He asks her if she recognizes the names Mr. De Boer and Mr. Van Grunsven. Elsje says she knew both men. But neither name is in the letter Olivier has in front of him. He made them up to test her.

Elsje’s sons realize she can be of no further help. Olivier stops asking questions, and Lodewijk quits filming. For the time being, they’ll let their grandfather and the CIA be. They have more important things on their minds right now: arranging their father’s funeral and finding a nursing home for their mother. The rest can wait.

Olivier and Lodewijk de Bruijn have no way of knowing that in opening that envelope, they’ve uncovered the secret role played by the Dutch in one of the Cold War’s most notorious eavesdropping scandals.

The Family Secret

More than a year and a half later, Lodewijk de Bruijn and I are sitting in Gauchos restaurant on Beethovenstraat in Amsterdam. We’re having the all-you-can-eat spareribs, just like we used to 15 years ago, when they couldn’t bring them out fast enough. We’ve come here for old times’ sake. I haven’t seen my high school friend for about a decade.

Two weeks ago, Lodewijk sent me a Facebook message that made this journalist’s heart beat faster. He wrote:

I really enjoy reading your work. So I thought of you recently when I was talking to my brother about a thrilling family secret that came to light after my father died. It’s got Russians (hot these days) and eavesdropping (your journalistic specialty)... I can just see the puzzled look on your face, ha ha... ‘What in the world is he talking about???’ I’d love to tell you the story sometime.

Take care,

Lodewijk

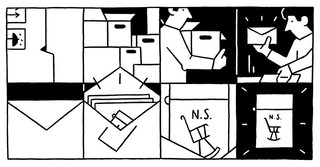

At Gauchos, we talk for hours – about work, old friends, buying houses, having kids. Over coffee, after a single plate of ribs each, Lodewijk pulls an envelope out of his backpack.

Here it comes: the family secret.

Photo from private collection

Lodewijk takes the typed pages and lighter out of the envelope. He holds out the stainless steel Zippo to show me the engraving: “N.S.,” “1960” and a line drawing of a midcentury armchair.

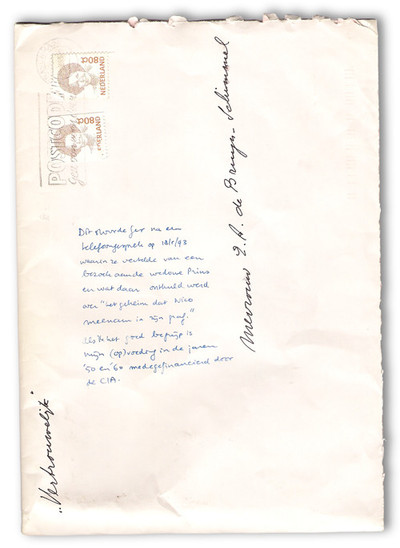

Lodewijk points to notes written on the envelope and letter in the hand of his mother, Elsje Schimmel. From these notes, the brothers immediately knew the initials N.S. must refer to their grandfather Nico Schimmel, who died in 1991.

So the lighter was his, but someone else had written the letter. On the envelope, Elsje has noted that she got it from her mother, who in turn got it from the widow of an old coworker of Nico Schimmel’s. That coworker’s name was Gerhard Prins.

In cramped script, Elsje has written:

[My mother] sent me this after a phone conversation in which she told me about going to see the widow Mrs. Prins, who told her about “the secret Nico took to his grave.”

“‘The secret Nico took to his grave?’” I say. “What secret was that?”

Lodewijk turns the envelope over and shows me another of his mother’s scribbles.

If I understand correctly, my upbringing in the 1950s and ’60s was funded in part by the CIA.

Illustration by Lennard Kok

I glance through the letter. In it, Gerhard Prins describes in detail three “relics” he had in his possession: an engraved Rolex, a stainless steel Dupont lighter and a plaque commemorating 30 years of “outstanding and dedicated service.”

According to Prins, he received these items as gifts from the Central Intelligence Agency. In the early 1950s, he writes, the company he and Nico Schimmel worked for – the Dutch Radar Research Station – started working closely with the U.S. spy agency. According to his letter, written in the early 1990s, the relationship lasted from 1954 until at least the time of writing and had to do with a highly secret operation code-named Easy Chair. The project had the attention of the U.S. and Dutch intelligence services’ top brass, Prins says.

His notes make my head swim. The story, written in old-fashioned Dutch, is incomprehensible at times. Prins alternates between technical descriptions and thrilling anecdotes. For instance, he recounts with relish how a few staffers from the Dutch Radar Research Station helped representatives of the CIA and the Dutch national security service (the Binnenlandse Veiligheidsdienst, or BVD), successfully bug the Soviet embassy in The Hague. He also reveals the remarkable fact – assuming it’s true – that Allen Dulles, the notorious director of the CIA in the early years of the Cold War, flew to the Netherlands especially to see how Operation Easy Chair was coming along.

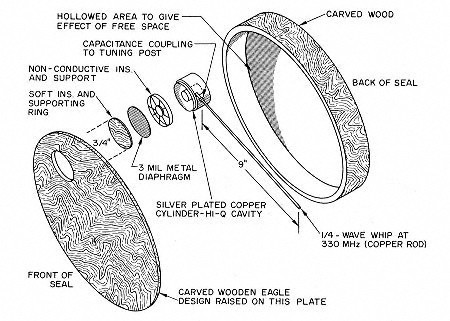

From my initial skim of Prins’ letter, Easy Chair appears to have been an eavesdropping project, for which the CIA approached the Dutch Radar Research Station in the 1950s to ask it to reproduce a highly sophisticated bugging device. “We were told,” Prins writes, “that this device had been found in the back of an armchair. Our project was accordingly dubbed ‘Easy Chair.’”

I stare at the engraved lighter lying on the table. Easy Chair. I don’t understand most of the technical stuff, and the history is news to me. Still, my ears have pricked up. The information is too specific, and Gerhard Prins’ tone too serious, to simply dismiss the story as fabulation.

Lodewijk says he and his brother had the same thought when they found the envelope. But their mother, Elsje, was no longer capable of answering the many questions they wanted to ask. And it’s not certain she could have even if her faculties had been intact. Judging from her notes, the letter and Zippo confused her too. “Why doesn’t the name Schimmel appear anywhere in these notes?” she writes on the back of the envelope. “Was Prins trying to protect him? Or ignoring him out of hatred?”

It is undeniably odd. In his letter, Gerhard Prins names four coworkers he says were involved in Easy Chair. Lodewijk’s grandfather Nico Schimmel isn’t among them. But the lighter engraved with an easy chair and his initials would suggest otherwise.

“Do whatever you want with them,” Lodewijk says at the end of the evening. It would be nice, he says, if he and his brother could find out more about their grandfather. Maybe Elsje’s questions can finally be answered. Maybe we can figure out how much of Prins’ story is true. Lodewijk and I say good night. On the way home, I try to imagine how it must feel to find something like this when your father’s just died and there’s nobody left to explain.

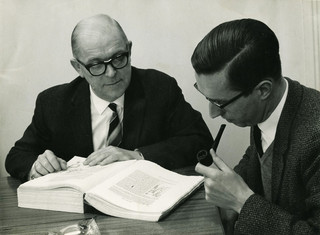

The Story

“If these notes are true,” Cees Wiebes tells me two weeks later, “they turn our idea of the Netherlands’ role in the Cold War upside down.” We’re drinking coffee in a café in Amsterdam; I’ve just shown him Gerhard Prins’ notes. After my dinner with Lodewijk, I knew two things for sure: one, this could end up being a big story, and two, I wouldn’t be able to tell it alone. Who better to ask for help than Cees Wiebes, the author of numerous books on spy agencies and eavesdropping operations and the man the NRC Handelsblad newspaper called a “walking Wikipedia of espionage”? Cees has the knowledge, access and contacts you need to unravel a historic classified episode like this one.

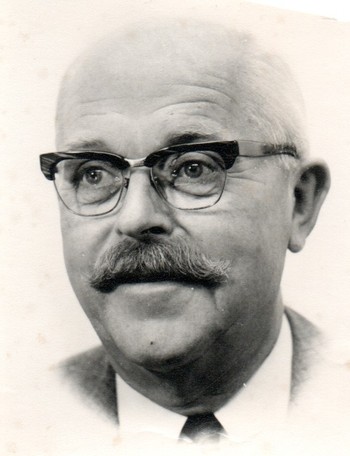

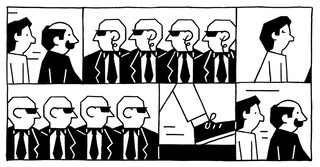

Gerhard Prins, private collection

Nico Schimmel, private collection

And he’s been retired for two months. He’d been working as a senior analyst with the Netherlands’ National Coordinator for Security and Counterterrorism since 2006, after more than 20 years teaching at the University of Amsterdam. His eyes are twinkling. We agree to work together. Now the research and the story belong to both of us. We christen our project Operatie Leunstoel – Dutch for Operation Easy Chair.

Cees explains why he’s so excited about Prins’ notes. According to the dominant view, the Netherlands and its agencies were the lapdogs of the United States after World War II. Washington pumped knowledge, money and manpower into the Dutch intelligence services through the 1960s. Marshall Plan aid wasn’t limited to goods and dollars but extended to helping the Dutch fight the Red Menace.

But Gerhard Prins’ notes, lying on the table in front of us, tell a different story. They suggest that in waging the Cold War against Russia, the Americans did nothing less than call on the Dutch for technical help. This is new, explosive information.

But how much of what Prins says is true? A single source doesn’t make a story. And we’ll have to go to serious lengths to confirm this one. We’re dealing with activities carried out by secret services, which don’t exactly make their archives freely available, and at least two of the four colleagues Prins named were dead, as was Prins himself.

Our quest will focus on the alleged relationship between the CIA and the Dutch Radar Research Station. Did Easy Chair really exist? If it did, was it successful? What was the secret Nico Schimmel took to the grave? And did the cloak-and-dagger stunt at the Russian embassy in The Hague really take place? If so, how on earth did they get the bug inside the building? We decide to start with the company that employed Nico Schimmel and Gerhard Prins: the Dutch Radar Research Station, which was based in the seaside town of Noordwijk until it closed in the 1990s.

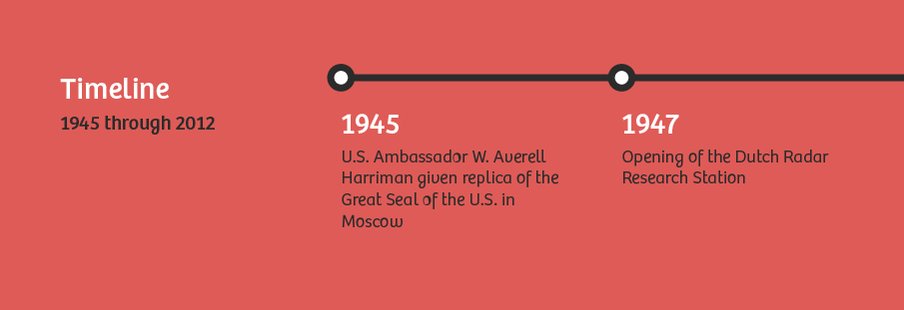

Newsreel coverage of the opening in 1947, with Sir Robert Watson-Watt in attendance (in Dutch only).

Dutch Radar

On July 7, 1947, the entire Dutch press turned out for the opening of the Dutch Radar Research Station. “Regardless of darkness or fog,” as the distinctive voice of the newsreel announcer explained, “radar makes it possible to determine the location of a ship or other object.” Dutch Radar’s introduction of the technology was a unique event in postwar Holland. It was to radically change aviation and shipping.

If you’re thinking a company with a name like “the Dutch Radar Research Station” must have been a staid 1950s outfit, think again. According to newspaper reports and conversations with people who were there, Dutch Radar in the early 1950s was the kind of business we’d call a startup today – hip, young, and unconventional – full of engineers and techies doing groundbreaking work with a promising new technology.

And as we soon discovered, Dutch Radar had a fascinating founder and director: the inventor, entrepreneur and politician Joop van Dijk.

The opening of the Dutch Radar Research Station in 1947, with J.M.F.A. "Joop" van Dijk (far right) and Sir Robert Watson-Watt (far left). Watson-Watt developed the radar technology used by Britain in WWII. Photo from private collection.

People who knew Van Dijk are unanimous: the guy was a genius. He not only had an extraordinary understanding of technology but a gift for politics and business. “A man of unusual stature,” says an old colleague from the political sphere.

At the age of 15, Van Dijk came up with a revolutionary invention, earning himself the sobriquet “the Dutch Marconi” in the newspapers. He devised a radio set equipped with a wavelength switch, which allowed the user to receive ultrashort, shortwave and longwave transmissions without changing the coils. The switch made the receiver more compact and simpler to operate. Before long, it was being used in every consumer radio made.

In World War II, Van Dijk served as head of the Government Communication Service (Corps Regeerings Berichten Dienst), a clandestine organization that built a secret network of radio transmitters, receivers and couriers across the Netherlands to enable communication between the resistance and the government in exile. After the war, Van Dijk continued to distinguish himself. In 1946, he cofounded the Freedom Party (Partij van de Vrijheid), which a few years later became the still-extant People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy, or VVD. He sat on the board until 1963.

With the kind of Rolodex Van Dijk had at 35, it’s no surprise that a number of eminent guests attended the opening of the Dutch Radar Research Station. They included the British ambassador to the Netherlands, the commander of the Dutch navy, and the director of the national meteorological service. The premises were officially opened by the secretary-general of the Ministry of Transport, Public Works and Water Management in the presence of the guest of honor: radar pioneer and British war hero Sir Robert Watson-Watt.

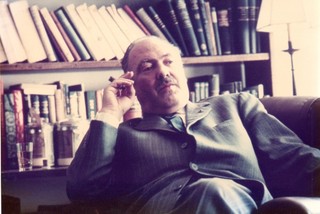

J.M.F.A. van Dijk, private collection

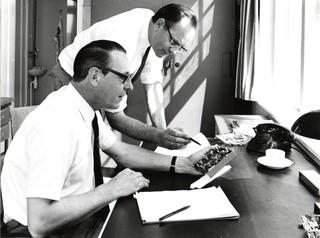

Also in attendance was 23-year-old Nico Schimmel, the future father of Elsje and grandfather of Olivier and Lodewijk. Van Dijk and Schimmel had met at the Government Communication Service, almost certainly during the war. Soon after the war’s end, Van Dijk had hired Schimmel, a student of mathematics and physics, to work at Dutch Radar because of his “great interest in and thorough knowledge of physics.”

Schimmel’s first job, in the runup to the opening on July 7, 1947, was to investigate and inventory the radar technology used in World War II by two military superpowers, America and Great Britain. He was Van Dijk’s first employee and protégé. Nico Schimmel would work for Dutch Radar for the next 25 years, first as head of the technical department and later as director.

We can’t tell whether anyone from the BVD, the national security service, attended the opening, although within a few years, its chief Louis Einthoven – nicknamed the Colonel – would play an important role for Dutch Radar. Van Dijk and Einthoven had become friends in 1940, and their relationship was deepened by a shared past in the resistance. But Einthoven is nowhere to be seen in the few photographs and film clips we find of the opening, although his body must by then have attained its mythic proportions. Nor does Van Dijk mention Einthoven in his description of the “illustrious gathering” in his unpublished memoirs, which we manage to lay eyes on later.

We doubt any emissaries of the U.S. spy agencies attended the opening, either. The first contact made in relation to Operation Easy Chair didn’t take place until years later – soon after the Thing was discovered in the official residence of the U.S. ambassador in Moscow.

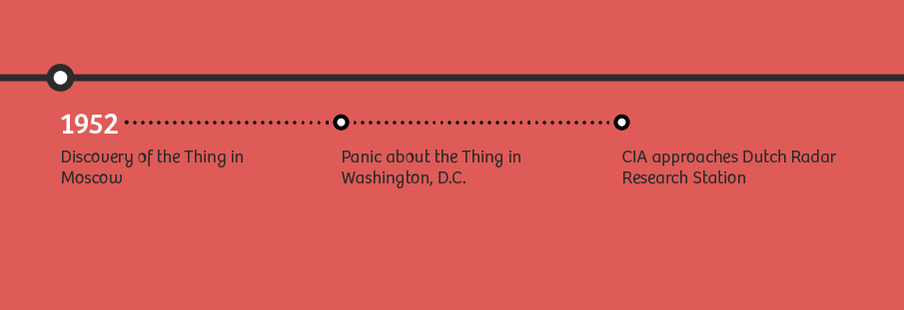

The Rug Merchant

September 12, 1952. A techie from Washington is searching the rooms of Spaso House, the U.S. ambassador’s residence in Moscow, for the umpteenth time. The Americans suspect the U.S.S.R. of listening in on them using advanced, hard-to-detect equipment (just as the U.S. is deploying its own most sophisticated gadgets to eavesdrop on Soviet diplomats). Radio waves seem to be involved: staff at the British and American embassies have accidentally picked up their own diplomats’ conversations. But so far, thorough searches for hidden wires, receivers and transmitters have yielded nothing.

The techie visiting Spaso House in September 1952, however, has a cunning plan. A year and a half ago, this man, Joseph Bezjian – nicknamed the Rug Merchant for reasons unknown – went through the U.S. buildings in the Soviet capital with a fine-tooth comb and found nothing.

This time, he’s going to succeed.

An obvious search for bugs would trigger alarm bells

Bezjian’s plan is to visit Spaso House explicitly as a guest, not a technical analyst. The Soviet secret service keeps a close watch on everyone entering and exiting the residence. An obvious search for bugs would trigger alarm bells, Bezjian reasons, and the Soviets would find a way to conceal the equipment.

So Bezjian arrives at the residence without equipment. He sets himself up in one of the guest rooms, goes to dinner in the evenings, plays bridge with fellow visitors. His instruments are brought in through a back door.

A few days later, part two of the plan kicks in. Working with George Kennan, the U.S. ambassador, Bezjian arranges a small theatrical performance. Sitting in his office, Kennan begins dictating a text to his secretary that sounds as if it contains important diplomatic information. Meanwhile, in the attic of Spaso House, the Rug Merchant switches on his instruments. He picks up a signal almost immediately. Someone is listening in.

Kennan keeps dictating, and the secretary keeps typing. The Rug Merchant goes down and makes his way around their office one step at a time, like someone prospecting for gold. Soon he’s traced the origin of the signal to a corner. There’s a small table with a radio and a few other objects on it. Bezjian summons a staff member to remove the items from the table. The signal he’s picking up doesn’t change.

The Great Seal

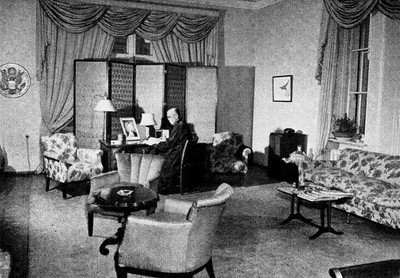

His gaze shifts to the wall above the table, where there’s a wooden carving of the Great Seal of the United States. In 1945, then-ambassador W. Averell Harriman had received the impressive handmade replica as a gift from Soviet children. The embassy’s technical department had thoroughly examined the Seal, and Harriman had ceremoniously hung it above the desk in his office. And so the bald eagle carved out of rare Russian wood had spent seven years proudly surveying the room.

Bezjian resolutely takes the piece of art down from the wall and – to the consternation of the ambassador, who is still dictating nonsense – starts smashing the wall to pieces with a hammer, looking for a transmitter.

He finds nothing. “When this failed to satisfy him,” Kennan would later write in his memoirs, “he turned these destructive attentions on the Seal itself.”

According to one version of the story, at this point Bezjian sent the ambassador out of the room, fearing a booby trap that might cause the eagle to explode. According to his own memoirs, Kennan stayed to watch.

One way or another, Bezjian had to hurry. The displacement of the wooden eagle had likely alerted the eavesdroppers. He placed the sharp edge of his hammer against a crack in the side of the carving and applied pressure. The eagle popped open like a book.

Russian listening device the Thing, found in hidden cavity in the wooden replica of the Great Seal.

There, in a wooden cavity, was the Thing. Bezjian carefully extracted it and, “[q]uivering with excitement,” showed it to the ambassador. The Thing was a tiny cylinder made of silver-plated copper with a thin copper antenna about eight inches long. It had no battery, no wire, no microphone. The expert technician Bezjian had never seen anything like it before. Yet he knew immediately that the object, which weighed all of about an ounce, was a wireless listening device.

“It is difficult to make plausible the weirdness of the atmosphere in that room, while this strange scene was in progress,” Kennan later wrote in his memoirs. “As this particular moment, one was acutely conscious of the unseen presence in the room of a third person: our attentive monitor. It seemed that one could almost hear his breathing. All were aware that a strange and sinister drama was in progress.”

The Trojan Horse

Our reconstruction of the discovery of the Thing is based on three sources: the memoirs of ambassador George Kennan; an article by Ken Stanley, chief technology officer of the State Department’s Diplomatic Security Service, who’s written extensively about the episode; and the official history of the Bureau of Diplomatic Security, authored by State Department historians.

All these sources originate from the U.S. political camp. And they’re ideologically freighted. Kennan calls the incident a “sinister drama”; Stanley describes Bezjian as “a real shadow Cold Warrior.” Certain details of their narratives are also impossible to verify. Did Bezjian really play bridge at Spaso House? Did he truly hold his equipment out in front of his chest? We cannot know.

The Great Seal is visible to the left, on the office wall beyond the Ambassador’s desk.

Yet we’re relying on these records anyway – and heavily borrowing from their details of setting – because it is an indisputable fact that the Thing hung undetected in the ambassador’s residence from 1945 to 1952. The episode was an embarrassing one for the U.S. Ken Stanley may like to focus on the Rug Merchant’s heroism, but the big trick was definitely pulled off by the Soviets, not the Americans. The Thing is sometimes referred to as the Trojan horse of the Cold War; in that analogy, the Americans are the gullible Trojans who allow the gift inside the walls, and the Soviets are the devious Greeks.

Nobody knows exactly what the Thing picked up during those seven years. But the State Department’s Ken Stanley, who had access to classified sources, describes the office that harbored the eagle as “the center of embassy operations for everyone working and living in the house.” So highly sensitive information would have been discussed there. CIA historian Benjamin Fischer recounts how Secretary of State George Marshall – he of the Marshall Plan – “discussed U.S. policy toward the U.S.S.R. within range of the hidden listening device” on a 1947 visit to Moscow. A Soviet spy who was involved in the operation later said, “For a long time, our country was able to get specific and very important information, which gave us certain advantages in prediction and performance of world politics in the difficult period of the Cold War.”

Ambassador Kennan, on the other hand, writes in his memoirs that the Americans “had long since taught [them]selves to assume that in Moscow most walls – at least in the rooms that diplomats were apt to frequent – had ears,” suggesting that the most sensitive information wouldn’t have been discussed within those walls.

Whatever results those seven years of eavesdropping yielded, the Thing had momentous consequences. It impacted international relations, “[giving] the Soviets a tactical and strategic edge in the battle for Cold War supremacy,” according to Stanley. It impacted spy agencies around the world; “with its discovery,” Kennan writes, “the whole art of intergovernmental eavesdropping was raised to a new technological level.” And last but not least, it impacted the little Dutch Radar Research Station in Noordwijk.

The Panic

From the White House to CIA headquarters, the discovery of the Thing drove the U.S. government and spy agencies to despair. Why? Because it demonstrated that the Soviets were streets ahead of the Americans when it came to eavesdropping technology. The CIA had been thrashed by its Soviet counterpart. Finding the Thing, Benjamin Fischer writes, had a psychological impact “akin to the Sputnik launch,” when the U.S.S.R. sent its first satellite into space, catching the U.S. completely off guard.

As American intelligence expert H. Keith Melton explains, the idea that the Soviets were eavesdropping on the American ambassador was alarming enough, but the first inspection of the device itself was even more shocking. Melton writes that the Thing elevated the art of audio surveillance to a level previously believed impossible, and that this sophisticated, complex technology put the capacities of the CIA in the shade.

Two questions were buzzing around Washington. One, how did the Thing work? And two, could we copy it and use it against the enemy?

The Americans did understand certain aspects of the Thing. For instance, they knew it was passive: that is, it stayed off except when it was remotely activated by electromagnetic waves. Because it wasn’t always on, it was almost undetectable. And since it didn’t need batteries, its lifespan was practically infinite. All in all, it was a work of unparalleled cleverness.

But they still couldn’t figure out exactly how it worked. And so the CIA found its way to Noordwijk. According to Gerhard Prins’ notes, they did so in 1954, about two years after the find. First, the Dutch Radar Research Station in Noordwijk received a visit from a CIA staffer “who wanted to know everything about the company and its employees,” Prins writes. “In late [sic.] 1954, this resulted in a vague research contract.” Why did they choose the lab in Noordwijk? We can only speculate. But according to Prins, the relationship between then-BVD chief Louis Einthoven and Joop van Dijk, Dutch Radar’s founder and director, was a decisive factor.

Thijs Hoekstra, private collection

At Admiraal, private collection

From Gerhard Prins’ notes, we know that Van Dijk confided in a few of his employees about Easy Chair. One, of course, was Prins himself. Another, according to the notes, was a man named Hoekstra, who was involved with the project in the early years but disappeared “overnight.” The only others Prins identifies as having worked on Easy Chair are Admiraal and Bijvoet. But what about Nico Schimmel, Lodewijk de Bruijn’s grandfather? Did he know about the project? His name doesn’t appear in Prins’ notes, but Schimmel was assistant director of Dutch Radar when the contract came in. It’s almost unthinkable that Van Dijk would have kept his protégé in the dark about Easy Chair.

On the other hand, Gerhard Prins’ notes state that an employee named Goldbohm harbored “ethical objections” to collaborating with the Americans and declined to get involved. Alongside that sentence, Elsje Schimmel has written in red ballpoint, “So did Schimmel.” Did her father have moral qualms about participating? But if he did opt out, how to explain that Zippo engraved with his initials and a chair?

The Villa

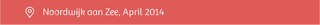

April 15, 2014. We drive to Noordwijk aan Zee and park on Koningin Astrid Boulevard, some distance away from an oceanfront villa named Wave Guide. It’s a bleak day, rainy and windy, and the sea is rough. The house is occupied but looks somewhat run-down.

From 1947 until the mid-1990s, the villa was the home of the Dutch Radar Research Station. Here, according to Gerhard Prins, five men secretly worked on Operation Easy Chair – at first, only in the evenings, and later in a special room.

At this point, we need a breakthrough.

Seventy-plus years later, descendents of a device invented by the Soviet Union to eavesdrop on its Western enemies are being flogged in an internal catalog of a U.S. intelligence organization

In the past month, we’ve learned a lot about the Thing and how it worked. Its inventor was the Russian Lev Sergeyevich Termen, a wizard with electromagnetic waves and world-famous as the father of the theremin, one of the first electronic musical instruments. In spring 1939, he was asked to build an ultramodern eavesdropping device: something wireless, microphone-free and undetectable. His client was no less than the man Stalin once jokingly referred to as “our Himmler”: Lavrenty Pavlovich Beria, the feared chief of the Soviet secret police.

Termen developed the Thing in one of the Gulag’s secret laboratories, where scientists were forced to work on technological projects for the motherland. It was the most advanced bugging system of its day, and it did exactly what Beria wanted it to. The Thing would help the U.S.S.R. spy on the U.S. ambassador for seven years.

A few months before our trip to Noordwijk, the Thing and the U.S. response to it suddenly became newsworthy again. Documents leaked by Edward Snowden – the former NSA contractor who’s been in and out of the headlines since June 2013 – revealed that the technology used in the Thing had not only constituted a highlight of bugging history but was still playing a part on the international eavesdropping scene.

In December 2013, Der Spiegel published a catalog of surveillance technologies used by the NSA and CIA to eavesdrop on rooms and other targets. Snowden’s documents showed that the U.S. was using these products against various foreign embassies in Washington. The devices in the catalog – with names like LOUDAUTO and ANGRYNEIGHBOR – work in different ways but are based on the same core technology as the Thing: they’re remotely controlled via radar waves. “These are virtually direct successors of the Thing,” eavesdropping expert Peter Koop told us.

History certainly isn’t averse to irony. Seventy-plus years later, descendents of a device invented by the Soviet Union to eavesdrop on its Western enemies are being flogged in an internal catalog of a U.S. intelligence organization.

Gerhard Prins’ notes appear to recount how the U.S. developed its own answer to the Thing with the Netherlands’ help. It’s a juicy story. But we need confirmation of his claims, and we’re not having much luck.

From private photo collection

For starters, hardly any publicly available information exists on Dutch Radar other than a few mentions in old newspaper articles and books and on websites. And facts about its founder, Joop van Dijk, are astonishingly thin on the ground too. The life of this man, who had such an impact on the Netherlands before, during and after the war, merits at least one solid biography by an eminent historian. Instead, we have to make do with brief passages in writings about other people.

For instance, Cees Fasseur, in his book Juliana & Bernhard, says Van Dijk had a “personal archive,” which Fasseur got a look at courtesy of Rudy Andeweg, a political science professor at Leiden University. When we approach Andeweg to ask if we can see the archive, however, he denies having it. After repeated urgings, he admits to possessing a manuscript of Van Dijk’s but adds, “You’re not getting it.” In an email, the professor says the documents relate only to the Greet Hofmans affair – a crisis that shook the Dutch royal house in the early 1950s, in which Van Dijk apparently played a key role.

We have no choice but to keep looking for Van Dijk’s archive. It could prove a goldmine for our story.

(Almost a year later, when we tell Van Dijk’s daughter that Andeweg has a manuscript of her father’s, she reacts with surprise. She’d believed, she says, that she was the only person in possession of any of her father’s papers. When we emailed Andeweg to tell him Van Dijk’s daughter would like to have the manuscript, he didn’t reply.)

In front of the villa, rain pattering on our umbrellas, we take stock of our investigation so far. Our hopes of finding eyewitnesses to Easy Chair have pretty much been dashed. In his notes, Gerhard Prins names four coworkers he says were involved. Two of them – Van Dijk and a man named Admiraal – are dead, as is Prins himself. A third, called Hoekstra, disappeared “overnight” in the late 1960s, according to Prins, and considering Hoekstra was born in 1920, he’s likely to be dead too.

A few weeks ago, we’d had a surprisingly easy time tracing the fourth employee: a man named Jan-Albert Bijvoet. According to Prins, Bijvoet was “removed” from the project “because of interpersonal difficulties.” In our email exchange with the 88-year-old engineer – who now lives in the U.S. – however, it quickly became apparent that he would be willing to speak on the record only if the intelligence services had released their files on Easy Chair. In other words: no dice.

Ed Admiraal, the son of At Admiraal, one of the four men named in Gerhard Prins’ notes – and a former employee of Dutch Radar, like his late father – declined to cooperate for the same reason.

Our chance of talking to anyone who was directly involved seems dead in the water. We’ve reached out to a few former members of the BVD and the marine intelligence service. But they either didn’t want to talk or said they couldn’t remember anything. So we’re going to have to find other sources.

We’ve been unable to find any publicly available information regarding the Dutch Radar’s relationship to the Thing, Operation Easy Chair, or the CIA. We did find a lone indirect reference, in Molehunt, David Wise’s 1992 book about the CIA’s search for a Soviet spy inside its ranks. “The effort to copy the Soviet bug that had been discovered inside the Great Seal was given the code name EASY CHAIR by the CIA. The actual research was being performed in a laboratory in the Netherlands.”

The Dutch Radar Research Station holds a demonstration in the dunes along the Dutch coast, private photo collection

Since Wise doesn’t cite a source for this information, we don’t know where he got it. In the book, he leans heavily on interviews with Peter Karlow, the high-ranking CIA man in charge of Easy Chair. We hypothesize that Karlow shared this information with Wise. But Karlow is dead, and Wise doesn’t respond to our queries.

Not long before, Spycatcher, the 1987 international bestseller by Peter Wright, a former agent for the British counterintelligence service MI5, had led us down the garden path. Wright writes that the Americans, after finding the Thing in the Moscow embassy, appealed to MI5 for help “in desperation.” He says not a word about any Dutch agency or company.

Though we can’t rule out the possibility that the Americans hedged their bets, we find odd Wright’s claim that he successfully copied the Thing for his country soon after being asked to do so. Likewise, his assertion that the Americans ordered 12 replicas and “rather cheekily copied the drawings and made twenty more.”

The experts didn’t take Spycatcher too seriously, though. In many ways, Wright paints an extremely one-sided picture of history. After lining up the known facts, along with a statement by the aforementioned CIA man Peter Karlow that Wright was lying and that as of 1959, seven years after the Thing’s discovery, the CIA still had no clue how it worked, we decided to set Spycatcher aside.

In the national archives in The Hague, we’ve combed through the papers of ministries, politicians and officials from the period and come up empty-handed. The secret collaboration between Dutch Radar and the CIA, which the BVD also had a hand in, was skillfully kept off the books – the public ones, anyway.

Illustration by Lennard Kok

Splashing our way past the villa one last time, we realize we’ve pinned our hopes on the spy agencies’ archives. We’ve submitted public information requests to the NSA and CIA in the United States and to the BVD’s successor organization, the AIVD, and the marine intelligence service in the Netherlands. It will be some time before they reply.

Schimmel on the villa’s balcony, private photo collection

After three months of research, the net result is that we’ve failed to confirm a single one of Gerhard Prins’ fundamental assertions. Did Operation Easy Chair exist? Was it successful? And the numerous questions his letter raises also remain unanswered. Why, for instance, did the CIA single out the little Dutch Radar? And what exactly was it that Nico Schimmel knew?

Standing in the rain outside Wave Guide isn’t making us any the wiser. In the 1950s and 1960s, outlandish rumors made the rounds in Noordwijk about what went on behind those white walls. We’ve heard tales of around-the-clock security and of military vehicles driving around at all hours.

We’d love to write down those stories. But without confirmation, we can’t.

The BVD Man

Cees has done it. He’s arranged for us to meet with an ex-BVD agent. Our rendezvous takes place at a chain hotel along the highway. The man – let’s call him X – worked on eavesdropping jobs beginning in the 1960s. And he’s got plenty of juicy anecdotes to share: about a device hidden right in the Polish embassy’s front window, a conference table at the Czech one that was “packed with bugs,” permanent listening posts at the Amsterdam Hilton.

We listen to his thrilling tales, order a second round of coffee, and then we get what we came for. Yes, X tells us, he knew about Operation Easy Chair. Yes, the BVD and Dutch Radar were part of it. Yes, it really happened. We practically jump out of our seats. Operation Easy Chair was real, not a figment of Gerhard Prins’ imagination. But, the ex-BVD man adds, the listening device Dutch Radar made wasn’t a success; it didn’t work very well. The BVD scrapped it in the early 1960s and switched to different technology.

Schimmel and radar equipment at the Dutch Radar Research Station, private photo collection

Cees and I look at each other in surprise. Prins’ notes say exactly the opposite, we tell X. In fact, they recount how Easy Chair’s success set in train a rich, productive relationship with the CIA that lasted almost four decades. Why else would the agency have given Prins a plaque in 1984 for “outstanding and dedicated service,” and a stainless steel Dupont lighter engraved with his initials and a thank-you nine years before that? X is surprised to hear about this. As far as he knows, the bugs didn’t work.

We say goodbye to X. He’s briefly taken us back to the days of Operation Easy Chair, and that’s useful for our story. But our witness has presented us with difficult questions, too. For instance, why did the Americans keep working with Dutch Radar if the BVD deemed its work below par? Did the BVD’s top brass know something the guys in the field, like X, didn’t? Did the Noordwijk lab make other bugging devices for the spy agencies? Are we ever going to find out?

The Spy Agency

On a warm September day, we stand at the entrance to the headquarters of the BVD’s successor organization, the Dutch General Intelligence and Security Service (Algemene Inlichtingen- en Veiligheidsdienst, or AIVD), in the town of Zoetermeer. Four men are in front of us in the security line. “Ill-fitting suits and cheap shoes,” Cees whispers. “CIA, definitely.” As they walk through the door one by one, show their passports, empty their pockets, lay their bags on the belt and walk through the metal detector, we hear them talking to the guards.

You could cut the American accents with a knife.

We’ve come here to get information about the U.S. and Dutch spy agencies’ collaboration on a clandestine project. Edward Snowden’s recent revelations have raised questions in the Netherlands about the Dutch agencies’ murky relationship with the NSA. And now here they are, right under our noses: American spies on foreign soil, paying a working visit to their faithful allies.

Illustration by Lennard Kok

We’re led through the big building to a stuffy little room. Two AIVD lawyers and a minutes secretary sit across from us. The hearing – which is what this is – lasts an hour. We’ve asked the AIVD to release documents on Operation Easy Chair held in its archives, but it doesn’t want to. So we’re here to present our case.

We submitted our request more than six months ago. On the basis of Dutch legislation on government openness and the intelligence services, we sent a list of specific questions pertaining to the Dutch Radar Research Station, Operation Easy Chair, a visit to the Netherlands by CIA director Allen Dulles, the CIA and BVD’s cooperation on the development of advanced eavesdropping equipment, and joint bugging operations against foreign embassies in the Hague.

And now here they are, right under our noses: American spies on foreign soil, paying a working visit to their faithful allies

Four months later (the statutory period is three), the AIVD sent an answer: No.

Yes, it said, we found information in our files that fulfills your search request. But if that information were made public, the agency argued, it could jeopardize national security and damage the Netherlands’ relationship with the United States.

We figured the reply could mean one of three things. The agency was giving us its standard reply to requests for information, or we’d stumbled on an operation that was still of vital importance to Dutch and American national security, or else the refusal was a symptom of the AIVD’s knee-jerk secrecy.

Putting our money on options one and three, we filed an appeal.

Prying information out of a secret service is by definition difficult. Secrecy is the raison d’être of intelligence and security agencies, and there are excellent reasons for that. But it makes it hard – and sometimes downright impossible – to learn much about them. Doing historic research on secret services, you run up against plenty of closed doors: agencies would often rather keep things secret. Information, even about operations more than half a century old, is released in dribs and drabs.

Today is our chance to explain our appeal in person. We need to get the lawyers to review their decision and let us have the documents. We have a trump card: Dick Engelen, house historian for the BVD and AIVD, has already described in detail the BVD’s relationship with the CIA in the 1950s and 1960s and disclosed how the agencies worked together against the Soviets during the Cold War. So why should the agency be so reticent now, years after deciding to publicize details of the episode?

Besides, we say, bluffing slightly, we’ve already got enough information on Easy Chair to publish our story. The requested information will merely fill a few holes.

The lawyers promise to reconsider our request.

Afterward, we get a brief tour of the “museum” in the AIVD’s lobby. A handful of glass cases contain typical spy gear – a walking stick with a secret compartment, a hollow-heeled shoe, various eavesdropping devices.

Nice, but they’re no Easy Chair.

The Breakthrough

Five months later, Cees calls. The AIVD is releasing the documents. Our arguments at the hearing in Zoetermeer convinced the lawyers. We receive an explanatory letter from the secretary-general of the Ministry of the Interior and a 50-page sheaf of archival materials. Jackpot.

The good news coincides with the FBI’s out-of-the-blue release of a series of documents on the Thing. So we’ll be able to bolster the story of Operation Easy Chair with new hard facts straight from the source. We’ve got our breakthrough.

Illustration by Lennard Kok

In an Amsterdam café, we eagerly study the files. The FBI documents are full of details of the Americans’ suspicions about a bug in their Moscow embassy and their various attempts to find it.

The documents make it indisputably clear for the first time what a panic the Thing caused in 1952 Washington. They include top secret reports by hastily formed working groups, communiqués to and from various government agencies, periodic reports on how the Thing was thought to work, and vague ideas for how the United States might be able to deploy replicas of it. In 1952, for instance, the U.S. Army considered using such devices for communication at the front during wartime.

Also among the documents are copies of communications with the British embassy in Washington. These seem to indicate that Britain did indeed have a hand in analyzing the Thing, but whether it did so as successfully as Peter Wright claims in Spycatcher cannot be verified; whole sections of text have been redacted.

President Harry Truman, we learn, took a close personal interest in the Thing. Truman ordered his national security council to make it a top priority to figure out how the bug worked. Virtually all of Washington was mobilized: the FBI, the NSA, the CIA, the departments of State, Defense and Justice. The Pentagon. The Atomic Energy Commission. The Navy, the Air Force, the Army. Every one of them did what it could to try to solve the mystery. But we find no mention of the role of the Dutch in the FBI file – nothing about Dutch Radar, the BVD, or eavesdropping in The Hague, let alone Joop van Dijk or Nico Schimmel.

Fortunately, though, the packet of BVD documents turns out to be a gold mine of key evidence and new information. For instance, we find out that the CIA, via the BVD, asked Dutch Radar to help with its investigation of the Thing in 1952, and not 1954, as Gerhard Prins says in his notes. That means the U.S. contacted the Netherlands almost immediately after finding the bug in September 1952.

Another confirmation: the Americans did indeed contact Dutch Radar through BVD chief Louis Einthoven and his resistance buddy Joop van Dijk.

An interesting detail: the lab wasn’t the BVD’s first choice. “Philips was considered as a possibility,” we read. “However, the company was uninterested in ‘small research projects.’ The Radar Research Station in Noordwijk was therefore called in [...].”

It was a bad call by the Eindhoven-based lightbulb company. That “small research project ” eventually netted the little lab in Noordwijk millions.

(Oddly enough, this statement about Philips from the BVD’s archives flat-out contradicts the unpublished memoirs of the agency’s then-director, Louis Einthoven, to which we gained access in June 2015. Einthoven writes that the Americans didn’t want to ask Philips because they were afraid secrets could leak out of such a large company.)

And finally we find out how the Dutch-made bug was smuggled into the Soviet embassy in The Hague. Though the technology enabled wireless, battery-free eavesdropping, the bug still had to be planted in the right room. But how? Gerhard Prins had already given us a hint in his notes: “In a shipment of office furniture being held in a customs warehouse for the ambassador, the BVD concealed one of our PEs (passive elements) in the leg of a desk.” His statement is confirmed on at least nine of the 50 pages of the BVD file.

Now we can reconstruct the planting of the bug down to the most exquisite details.

The Desk

In November 1958, the BVD learned from an informant that the Soviet embassy in The Hague had ordered some furniture. It had done so through the Netherlands’ central government purchasing office for “office equipment, cleaning supplies and household goods.”

It was the perfect chance for the BVD and Dutch Radar to plant their bug inside the Soviet embassy. Initially, the BVD approached the company that was building the furniture. Its objective: “to have an ‘Easy Chair’ placed in one or more items of furniture.”

When the company’s director refused to cooperate, the BVD turned to the head of the government purchasing agency. He “proved favorably disposed to our plans, but he saw no practical way of assisting us.” His agency did not deal directly with the furniture; the parties ordering it communicated with the companies themselves.

However, the head of the purchasing office suggested an alternative plan: “Ask the [redacted] company to bring the furniture from the factory to [redacted]. Invite the Russians to the inspection and make it clear to them that the transfer is a gesture toward them, taking place in The Hague and in a more pleasant environment. Potential mistrust will therefore be prevented.”

It was a good idea, but it, too, depended on the furniture company’s cooperation. It was time for the BVD to exert some pressure. “[Redacted; probably the name of a BVD officer] is of the opinion that [redacted] can be persuaded to cooperate.”

How exactly this was accomplished is unclear, but it was.

“Bills of production” showed that the Soviets had placed an order for a “pair of end tables, a round coffee table and a desk, all to be made of walnut.” The choice was quickly made.

“On Sunday, November 23, the ‘Easy Chair’ was placed in the desk.” Three days later, the desk was painted; that evening, “the tiny hole in the desk, which had closed during ventilation, was restored and the installation was tested [...]. The installation worked, though the sound quality was not ideal [...]. On 27 November, the Easy Chair was inspected one more time, since the desk was to be polished that day. [Redacted] reported by telephone on November 29 that the furniture would be delivered to the RE [Russian Embassy] on December 10.”

Prins and Admiraal studying radar equipment, private photo collection.

The BVD had successfully dispatched its Trojan Horse. Hidden in the leg of a walnut desk in the Soviet embassy in The Hague was a bug built by Dutch Radar. The men at the lab had worked on the device for six years. It was wireless, microphone-free and undetectable.

At that point, as far as they knew, their work for the CIA stemmed from the discovery of a bug in the back of an armchair; hence Easy Chair. They had never heard of the Thing. That changed in May 1960, when the Thing hit the international headlines.

The Trump Card

The smiling faces in the U.N. Security Council chamber belied what was at stake. The Soviets had been ranting and raving for several days straight. The U.S., they said – and not the U.S.S.R. – was starting a war, and it needed to be acknowledged on the record, here, on New York’s highest international stage.

The Cold War was at its peak. A few weeks before, on May 1, 1960, the U.S.S.R. had shot down an American U-2 spy plane in Soviet airspace. The U.S. reacted by denying it had been spying. Inconveniently, the Soviets found the wreckage of the plane, complete with cameras, more or less intact. And the pilot, Gary Powers, had survived. So there wasn’t much point denying espionage.

In the Security Council chamber, the Soviet foreign minister, Andrei Gromyko‚ characterized the U.S. as irresponsible and untrustworthy, calling and its foreign policy provocative, even ‘piracy.’ The Soviets introduced a resolution to condemn the United States in unprecedentedly harsh terms and label the country an ‘aggressor.’

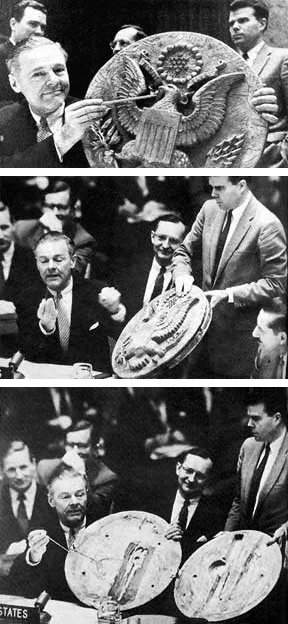

The U.S. was facing increasing pressure. Then Henry Cabot Lodge, the American ambassador to the United Nations, played his trump card.

An assistant came forward, carrying a wooden replica of the Great Seal of the United States. “Now here is the Seal,” Cabot Lodge said. “I would like to show it to the council.” Cabot Lodge opened the Seal at the side, exposing the cavity in which the Thing had been hidden. “You can see the antenna and the aerial… It was right under the beak of the eagle.” The Thing, Cabot Lodge informed the council, had hung on the wall in the U.S. Embassy in Moscow for seven years. Clearly, the Soviets, not the Americans, were the true villains.

Cabot Lodge shows the Thing in The Great Seal during a meeting of the U.N. Security Council

For a time, the Thing stood squarely in the spotlight. And this time, the enigmatic device worked in the United States’ favor. A day later, seven of the Security Council’s nine members rejected the Soviets’ resolution.

Cabot Lodge’s performance was hypocritical, of course. Since finding the Thing in 1952, the Americans had done everything in their power to copy it in order to avail themselves of the technology. And not long before Cabot Lodge expressed moral outrage at the Soviets’ actions, the U.S., with the help of Dutch Radar, had begun eavesdropping on the Soviet embassy in The Hague, using a derivative of the Thing.

News footage of Cabot Lodge’s diplomatic poker game traveled around the world. The tale of the Great Seal bug has been a classic of international espionage history ever since. The story made its way to Noordwijk aan Zee, where it must have come as something of a shock. Gerhard Prins writes: “Its true background only became known in 1961, when at a meeting of the United Nations the American representative displayed this element and announced that it had been found inside a plaque of the American eagle that the Russians had given as a gift [...].”

How did the men of Dutch Radar react? What did they think when they realized they were players on the world’s biggest espionage stage?

Newsreel of the Thing being presented to the U.N. Security Council in May 1960

The Daughter

On a glorious April day, Sylvia van Dijk picks us up at the train station in Mons, Switzerland in her gray Toyota. We drive through the hills to her house near Lake Geneva. Van Dijk, 75, has lived in Switzerland ever since her father, Joop, moved his family here from the Netherlands in 1960 because of the tax environment. “He didn’t want to sacrifice himself anymore,” she says, in flawless Dutch.

Walking into her house, we spot a thick gray folder lying on the dark wooden table. We’re here for Sylvia and her memories, but also for the papers of her father, Joop van Dijk, the erstwhile head of Dutch Radar. Cats wander in and out through the open doors, white wine and pretzels swiftly appear on the table (it’s not yet noon), and smoking is allowed. All the ingredients are in place to make our visit to Sylvia van Dijk a highlight of our quest.

Proudly she takes a book down from a shelf. It’s the classic The Craft of Intelligence, the bible of late-20th-century American espionage. Sylvia opens the book and shows me the signature of its author, master spy and ex-CIA director Allen Dulles. In his notes, Gerhard Prins says he and Hoekstra received signed copies of the book; evidently Van Dijk was also thusly honored.

We open the gray folder and enter Joop van Dijk’s life. We’re immediately struck once again by what an extraordinary life he led. Make a list of key words from his biography and you’ll get a fair sketch of what was going on in the Netherlands from about 1930 to 1970.

Illustration by Lennard Kok

For instance, the file contains an account of a spring 1950 visit to the Dutch Radar Research Station by Greet Hofmans, a faith healer who caused turmoil in the Dutch royal house. The anecdote has nothing to do with Easy Chair, but it’s a fun read.

“I took her around the laboratory and showed her various radar devices in operation. Over tea, which was taken in my office, Hofmans wished to impart to me a few messages from on high and requested that I write down her mystical utterances. There followed an incoherent tale of atoms, electrons and waves, vibrations and magnetic forces and promises of great discoveries. I wrote it all down. It was nonsense, impossible to make heads or tails of. When she asked me whether I had understood everything, I replied that it was so encompassing and profound that I wished to take time to digest it. She nodded understandingly and said, ‘You will see that everything will turn out just as I have said.’”

Van Dijk writes at length about Dutch Radar – about founding the company, radar technology, opening the lab, developing the business, expanding abroad. But on Easy Chair, the CIA, the Thing and eavesdropping, he is silent.

His daughter, however, is not.

Around lunchtime, we drive to a nearby village and settle in at a sunny outdoor table at a restaurant. Even as a little girl, she knew, Sylvia van Dijk tells us. In the evenings, with the family sitting around the table together, her father liked to tell stories, with his cognac in one hand and a cigar in the other. “It was like a detective book,” she says.

Sylvia’s anecdotes match up with Gerhard Prins’ notes. She’s able to reconstruct the operation at the Soviet embassy in The Hague with reasonable precision and still clearly remembers her father being summoned several times to the CIA’s headquarters in Langley, Virginia. She also tells us the CIA brought briefcases full of dollars to Noordwijk. But every time her father told one of his stories, he swore his children to secrecy, Sylvia says. “He was always afraid they’d kill us.” She’s kept her promise ever since – until today.

He devised a special smuggling method: a pair of underpants adapted to accommodate wads of bills.

She still vividly remembers the family’s summer vacations at Wave Guide. She loved it there. They’d play on the beach all day, and in the evenings, their dad would take them “out on the town” at the nearby grand hotel Huis ter Duin. The kids weren’t allowed in the villa’s offices or basement, where the engineers worked. But they snuck in anyway.

Yes, Sylvia says, CIA agents often visited Dutch Radar, and the Van Dijks’ house in Amersfoort too. Her dad went to the States at least four times. He always sailed on the Holland-America Line; he was afraid to fly. Even after the family emigrated to Switzerland, Americans used to come to the house. She’s not sure what for, exactly; she thinks probably something to do with money.

Speaking of money, Joop van Dijk took those briefcases of dollars to Switzerland on the train. He devised a special means of smuggling them: a pair of underpants adapted to accommodate wads of bills. “At home, we called him the Bear,” Sylvia tells us. “And we called those pants his bear pants.” It still sends her into fits of laughter.

One more thing: Van Dijk opened Swiss bank accounts for two other men from the lab; Sylvia can’t remember who. Not Nico Schimmel, as far as she recalls.

On the way back, Sylvia tells us she still vividly remembers the men of the Dutch Radar Research Station. Hoekstra was a “great guy” who used to take her fishing. Prins was “a little shy.” And Schimmel was “stern and distant.” She doesn’t know if he was involved in the American business. “It’s possible.”

On the plane home to the Netherlands, we scroll through the pictures we took of the papers in the folder. We read about the vital role Nico Schimmel played at the research station. He went to work for Van Dijk during or just after the war, when he was in his early 20s, and he never left. Schimmel was an indispensable part of the company, an authority on radar technology, and he took over as director after Van Dijk went to Switzerland.

So why didn’t Van Dijk open a Swiss bank account for his protégé? We’ll never know.

Nico Schimmel poses with a Research Station coworker, private photo collection

The Grandfather

I meet Lodewijk de Bruijn in a coffee shop in Amsterdam. It’s been almost a year and a half since we met at Gauchos for spareribs. His mother, Elsje Schimmel, died a few months ago at 65 from complications of Alzheimer’s. Lodewijk sits across from me, looking expectant. “The story is complete,” I say. “As complete as we can make it.”

We’ve been able to confirm most of the statements in Gerhard Prins’ letter. Operation Easy Chair existed, I tell Lodewijk, and the CIA approached Dutch Radar through the BVD in 1952. I recount the history of the Thing, mentioning its inventor, Lev Termen, how the device worked, and how the Americans found it. I explain how its discovery led the U.S. to pour millions of dollars into developing equivalent or superior eavesdropping equipment. Budgets were increased tenfold; new divisions were set up; every possible action was taken to eliminate the Soviets’ advantage.

Dutch Radar played a significant part in the mobilization, I tell Lodewijk. Some of the millions of dollars the Americans spent on eavesdropping technology flowed to Noordwijk aan Zee, to the company his grandfather Nico Schimmel ran for years. “Why did the CIA go to them?” Lodewijk asks.

“Joop van Dijk,” I say. His friendship with BVD chief Louis Einthoven opened the door to a collaboration; the flamboyant networker and the excellence of his lab did the rest.

A few days before my meeting with Lodewijk, Cees and I received Einthoven’s memoirs from the AIVD. In the days when he helmed the BVD, Einthoven writes, the CIA greatly admired the Netherlands. “The Americans were so convinced of the ingenuity and security of the Dutch that they came to me one day with the following problem. They had found a metal object in one of their embassies that was capable of allowing the enemy to listen in on what was said, unattached, with no connection to the outside world.”

Gerhard Prins says in his notes that the Dutch Radar Research Station worked for the CIA until “the early 1990s.” We have no reason whatsoever to believe this is untrue, I tell Lodewijk, but we haven’t been able to figure out what exactly the lab did for the agency for all those years.

We did discover that the BVD had been unaware of the relationship’s duration. Yes, the agency made the initial contact with the lab, and it was involved in the Easy Chair bugging operation in The Hague, but that was all. The BVD’s files and our conversation with its former agent X suggest that the Dutch spy agency was dissatisfied with the lab’s work. Were the CIA’s requirements less stringent, or was Dutch Radar making things for the Americans that the BVD didn’t know about?

One way or another, Louis Einthoven says in his memoirs that his “friend” (Van Dijk) got “filthy rich” working for the CIA. “He did,” I tell Lodewijk. In 1968, Van Dijk’s various companies racked up almost 20 million guilders in sales, according to his papers. And that’s not even counting all those train trips he made with his bear pants full of cash. According to a Dutch Radar anniversary booklet, the “peak years” for the company’s “American business” were 1968 to 1971. We’ve been unable to determine exactly how much money was involved.

This brings us to Lodewijk’s grandfather. What did Nico Schimmel know about Easy Chair? How involved was he? Elsje was probably right that her father’s salary was partly paid by the CIA, I tell Lodewijk. And I’m also willing to state with certainty that Nico Schimmel knew about Operation Easy Chair. The Zippo with the chair and his initials on it is still the best evidence we have.

Then there’s Nico’s close friendship with Joop van Dijk dating back to the war. Van Dijk speaks highly of Nico in his papers, and he gave him plenty of responsibility at the research station from the start.

Schimmel at work, private photo collection

But we still can’t tell Lodewijk why Nico Schimmel isn’t named in Gerhard Prins’ notes. Nor can we explain why Sylvia van Dijk was sure Hoekstra and Prins were involved in Easy Chair but was uncertain about Nico. And then there are those Swiss bank accounts Van Dijk opened for two other employees but, according to Sylvia, not for Schimmel.

“No, there wasn’t that much money” in either his parents’ or his grandparents’ household, Lodewijk says, let alone fat Swiss bank accounts. I tell him I’m sorry I wasn’t able to find out more about his grandfather. Operatie Leunstoel wasn’t just about reconstructing the CIA’s collaboration with Dutch Radar, it was also about figuring out what part Nico Schimmel had played in the whole business.

“I’m certainly not disappointed,” Lodewijk says. “Thanks to your research, I’ve found out more about my grandfather in the last year and a half than I did in 33 years.” He shows me a picture on his phone. “Look,” he says. “It’s a page from an old address book of his I found.”

I peer at Nico Schimmel’s neat, structured handwriting. Under E, there’s a phone number for the BVD, and underneath it, a direct number for the boss, Louis Einthoven.

Lodewijk smiles. “Even if we don’t know exactly what my grandfather’s role was, we still have our exciting family story, right? I mean, I haven’t seen any proof that he wasn’t involved.”

The Eyewitness

We figured he must be dead by now, but the voice at the other end of the phone is decidedly alert.

Thijs Hoekstra, 95, is alive, and he wants to talk.

“I was the outside man.”

The call makes for an unexpected epilogue to our year-and-a-half-long quest. Hoekstra, like Nico Schimmel and Gerhard Prins, worked at Dutch Radar. “I installed all that junk.”

By junk, he means bugs; by installed, he means he secretly planted them in embassies in the Hague in the 1950s and 1960s. “That’s what we did in the Cold War,” he says – “we” being the Dutch Radar Research Station, working with the CIA and BVD.

Suddenly, Gerhard Prins’ notes and the folders full of papers have a human voice. For the first time, we’re hearing the story of Operation Easy Chair from an eyewitness.

In the typewritten notes that started our quest, Gerhard Prins writes that “Hoekstra’s overnight disappearance” threatened Dutch Radar’s relationship with the CIA. Against a backdrop of Cold War espionage and international eavesdropping scandals, assassination springs to mind. Fortunately for Hoekstra, his reason for vanishing was less cloak-and-dagger: “I was overworked.”

The elderly man confirms crucial chunks of the story. He was part of the operation in The Hague.

The Operation

A truck with a canvas cover parks on Andries Bickerweg in The Hague. The burly driver gets out, fiddles around under the hood and walks off down the street carrying an engine part. What looks like a breakdown to passersby is in fact a joint eavesdropping operation by the CIA, the BVD and the Dutch Radar Research Station. Their target: the Soviet embassy at 2 Bickerweg.

The driver, “Herman,” is a high-ranking BVD officer. Sitting under the canvas in the back of the truck are a CIA agent and an employee of Dutch Radar: Thijs Hoekstra, the “outside man.”

Also in back is a device for transmitting high-frequency radio waves. There isn’t much time: a truck parked at the door of the Soviet embassy won’t go unnoticed for long. The men in the back aim the transmitter at the wall of the target and wait. They’re hoping to make contact with the leg of a desk inside the embassy.

Built into that leg is an ingenious piece of spy gear: the derivative of the Thing developed in the Dutch Radar laboratory. The men are beaming radio waves at the listening device’s antenna in order to activate it. They had been unable to contact the bug in the desk from their original listening post, in the attic of a school a few hundred yards down the street. The question is, were they too far away, or did the Soviets find the bug and remove it?

Hoekstra and the CIA officer hear a guffaw: the Soviet ambassador’s “big belly laugh” (as Prins calls it in his notes) is coming through loud and clear. The men in the back of the truck celebrate their amazing feat in silence.

Hoekstra and the CIA officer hear a guffaw: the Soviet ambassador’s “big belly laugh” (as Prins calls it in his notes) is coming through loud and clear. The men in the back of the truck celebrate their amazing feat in silence. An hour later, burly Herman comes back with the engine part and drives the truck away. Mission accomplished.

The Soviet embassy wasn’t the only one, Thijs Hoekstra tells us. Easy Chair was even more extensive than we thought. For instance, the Chinese embassy was targeted around the same time as the U.S.S.R.’s. That operation was less successful, but it makes just as good a story.

The biggest challenge in operations like these is installing the device. How do you get it inside the building? In this case, the unexpected death of a Chinese embassy employee presented an opportunity. The embassy was cordoned off so police could investigate, and Hoekstra and a BVD agent simply walked in. They hid the device in a screen in a prominent, strategic spot. A relative piece of cake. The men walked away in satisfaction.

But before the BVD could try to make contact with the bug, it discovered that the Chinese embassy was moving. Would the Chinese take the screen with them? If they did, where would they put it?

Hoekstra remembers peeking over the new embassy’s walls from the gardens of the nearby Peace Palace to see if he could spot the screen in one of its dozens of rooms. No luck. “We never saw it again,” he says 55 years later, roaring with laughter.

The Memory

“The CIA didn’t want the BVD to get everything,” 95-year-old Thijs Hoekstra continues on the phone. “They were paying for that equipment, you know? The BVD didn’t know about everything we were making for the Americans.”

Even he doesn’t remember for sure anymore. He wasn’t the techie, anyway; he just installed the junk, “put it out.” Besides, it’s been more than half a century. “I’m 95 years old, young man!”

Schimmel (left) and Prins (right), private collection

Yes, he did go to the United States “several times” with Gerhard Prins. They met with CIA people. And once he went with Van Dijk. “We went to CIA headquarters and talked to the top man.” Allen Dulles? He doesn’t recall.

The business about the Swiss bank account is true. Joop van Dijk set it up. “It was great,” Hoekstra says. Somewhere in his house in Britain, he still has the engraved Rolex that he, like Prins, received from their overseas friends. He also has a letter the agency sent him after he left his job at Dutch Radar because of burnout. The letter thanks him for services rendered. “Of course, you understand it wasn’t signed ‘the CIA.’ But you can take it from me, that’s who it was from.”

He remembers nothing about the Thing found inside the Great Seal at the U.S. Embassy in Moscow, or about Dutch Radar Research Station spending years unwittingly building a rival. “I never heard that story before.” Then, after a brief silence: “Yes, I do vaguely recall something. But only vaguely.”

And what about Nico Schimmel?

“Nico Schimmel didn’t know anything.”

Silence.

“Nico Schimmel knew there was something going on, but he didn’t know what.”

Silence.

“I think.”

—English translation by Laura Martz and Erica Moore. Original Dutch article published in September 2015.

More Operation Easy Chair:

These typed pages were the start of Operation Easy Chair

Here you can see a scan of the original envelope and typed pages that gave rise to this investigative piece.

These typed pages were the start of Operation Easy Chair

Here you can see a scan of the original envelope and typed pages that gave rise to this investigative piece.

Operatie Leunstoel: hoe een klein Nederlands bedrijf de CIA hielp om de Russen af te luisteren

The original Dutch article by Maurits Martijn on the clandestine role a small company in the Netherlands played in the Cold War.

Operatie Leunstoel: hoe een klein Nederlands bedrijf de CIA hielp om de Russen af te luisteren

The original Dutch article by Maurits Martijn on the clandestine role a small company in the Netherlands played in the Cold War.