Hi,

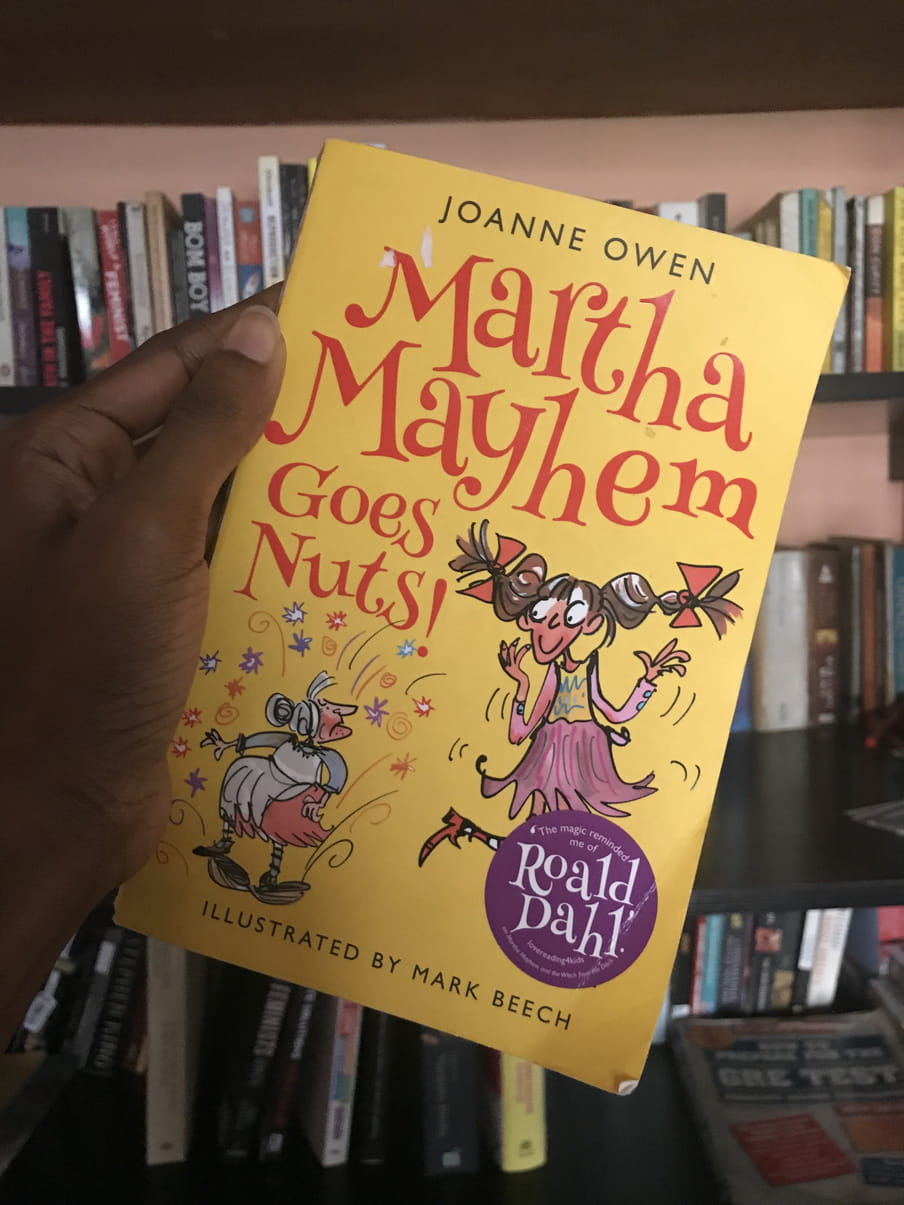

After finishing her online classes today, my seven-year-old daughter took a personality test she found in the epilogue of one of her books. Question two asked, “which weather are you most like?" Out of four options, she chose “a wild whirlwind.”

For the past 10 days, this wild whirlwind of mine has had to contain herself. She hasn’t seen her classmates or cousins. There’s been no going for ice cream or to the movies, no splashing in a swimming pool, and no childish altercations on the playground. She has stopped asking me when things will go back to normal, because my answer hasn’t changed. I have no idea when, or if, things will ever go back to the normal she used to know.

For those of you who follow The Other Shelf, the transnational book club I started here at The Correspondent, you’ll know that we’re currently reading Buchi Emecheta’s The Joys of Motherhood. The book was chosen to fit the woman-centric theme that was unquestionably relevant in the month of March, before the coronavirus took over our lives.

The Joys of Motherhood maps some of the drastic changes that took place in mid-20th-century Nigeria, through the eyes of an endlessly self-sacrificing mother named Nnu Ego. By the time we get to the end of the book, the beliefs and behaviours that were "normal" at the beginning of Nnu’s adult life have all but disappeared.

Unlike Nnu Ego, those of us who are living through this moment of global upheaval don’t have the luxury of decades of adjustment. The changes that are taking place in our social landscape as a result of the coronavirus are both immediate and unrelenting. Every day, I find myself struggling with feelings of disorientation and despair.

After sending out my newsletter two Fridays ago, I postponed my plans to go dancing at a favourite nightclub because my daughter fell suddenly ill. "I’ll just go next week," I decided. By the time "next week" rolled around, everyone in Lagos was being encouraged to stay at home because community transmission had begun. Now, I don’t know when next I will leave my house for any reason other than to buy food or medicine. I try not to worry, but it’s hard.

I can’t visit my father, who has always hated being cooped up, but who is over 60 and has chronic asthma so can’t risk being out right now. I worry about my grandma, who is 89 and in excellent health, but relies on regular meetings with church members, relatives, and community leaders in her neighbourhood to fill her days with purpose.

Staying at home all the time is my new normal, and the new normal for a lot of people around the world.

Yet, I realise how advantaged I am. I’m in a country like Nigeria in the midst of a growing healthcare disaster, and my biggest worries are only about how my family and I can survive an extended stay at home. For the vast majority of Nigerians, this virus poses a much bigger, more dangerous threat.

Unlike most of the 200 million people in my country, my various family members and I have safe homes with regular electricity and piped water. I have the privilege to work indefinitely from home without taking a significant hit to my income or quality of life. I have unlimited internet access which allows me to stay in touch with my loved ones all over the world.

Unlike medical personnel in my country, I will never have to put myself or my loved ones at high risk of infection, because I’ll never be in the line of fire with inadequate equipment. Unlike the urban poor in my city, I will never have to choose between catching the virus and going hungry. Unlike the semi-educated, I’m not likely to endanger myself by acting on false information about medicines that can cure it.

It’s been said by many people—because it’s true—that the novel coronavirus is exposing many of the deep flaws that existed in our old "normal". The illness itself doesn’t discriminate, but its effects will be unevenly felt in the long term because our societies do. Something else that’s being said a lot, also because it’s true, is that this crisis can offer us an unforeseen chance to address this social discrimination.

I realise that we’re all dealing with a lot right now, but it’s important to remember that this moment can also be a gift. We can use this time to ask ourselves how we can contribute to rebuilding our societies so that they are more equitable. We have an opportunity to demand, create and sustain a new normal in which we are more generous, more accepting, and more humane; in which respect, compassion, generosity and communal care are the foundation of our societies. We have a chance to recover in the direction of progress.

I really hope we take it.

Till next time,

OluTimehin

Want to receive my newsletter in your inbox?

Follow my weekly newsletter to receive notes, thoughts, and questions on the topic of Othering and our shared humanity.

Want to receive my newsletter in your inbox?

Follow my weekly newsletter to receive notes, thoughts, and questions on the topic of Othering and our shared humanity.