Today I - documentary film maker and correspondent Jos de Putter - present a very special project. Filmmaker Jaap van Heusden and designer Ruben Pater collected and designed a series of personal stories from Iran.

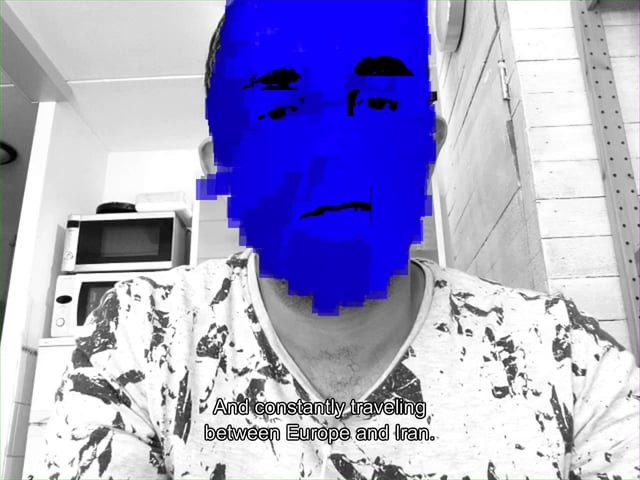

With their approach they explore a new kind of journalism - a very direct narrative form combined with an artistic presentation. This series of video selfies is bundled under the name Behind the Blue Screen, and you will soon find out why.

Van Heusden and Pater made use of a combination of face recognition software and art based technology which allows realtime transformation of video images. In this trailer, they present their project, which was supported by the Dutch Cultural Media-fund.

Besides, you will find their first three films we made, based on people’s entries, accompanied by an interview conducted by Karel Smouter, a journalist who travelled to the country for a number of times.

Behind the Blue Screen - Trailer

We were just boys. Nice boys, but seriously naive boys. In six visits to Iran, between May 2006 and December 2009, I played a ‘backpack journalist’ with several colleagues. Also dubbed tournalists.

This approach kept us out of Iranian prisons during the Green Revolution in 2009.

We could assure the military, who forcefully plucked us off the street, that we had no journalistic intentions and that we were just innocent backpackers. Our sources, it turned out, where less safe. After another trip, a half year later, our sources were questioned one by one about their contact with this crazy Dutch person with six tourist visas in his passport. Some of them were even given the choice: you go to jail for two years, or lose your right to study or have a business. They often chose a third option: running off to other places.

Furthermore, even journalists who have official accreditation find that working there is regularly made impossible.

Like journalist Jason Rezaian of The Washington Post who, together with his wife, has been in jail in Iran since July 23, 2014.

Filmmaker Jaap van Heusden and Ruben Pater decided on a different approach. They developed an app which allowed Iranians to tell their own story on a secure smartphone, behind a screen created by a moving blue mask.

A process of trial and error

Van Heusden: “It all started because we met Iranians in the Netherlands. The stories they told us about their home-country didn’t in any way resemble the image that we had gotten here through the media. Angry Islamic scholars, nuclear bombs, aversion to the West. An image that wasn’t recognized in Iran.”

The two decided to show that other side. “We searched for two years for a way to tell those untold Iranian stories in a safe way.” Van Heusden says. “This was a process of trial and error - especially error!”

Initially the two put their faith in technology. “We visited known hackers to learn how to send encrypted messages. They just laughed at us. They said you can send an encrypted message to that country, but just the fact that someone there receives a message like that, was according to them reason enough for a ‘visit’ from the intelligence services. The hackers were very clear: “If you do it that way, people are going to get killed!”.

Van Heusden and Pater didn’t let this criticism keep them down, and continued to search for a method that would work. They decided to give a secure smartphone to Iranians traveling back to their home-country. The smartphone would be passed from hand to hand until it finally arrived at the storyteller. “‘Sneaker-journalism’ we called it”. The devices containing the videos would eventually be brought back to the Netherlands.

When the footage arrived in the Netherlands the work of the duo really started. “We had to translate the videos and throw away dozens of them. Because the sound or the light wasn’t okay, or because the story just wasn’t good enough”. The trick was to constantly adjust our expectations. “We had been to Tehran and heard hundreds of stories that were really good. For example about home-brewed beer, a trend in some circles. The stories the two got back however, exceeded their expectations. “They are excellent storytellers, they know exactly what a good story needs. The stories were embellished and full of drama.”

The video below is a good example of this. “You hear someone talking about a party with lots of booze and weed that is rudely interrupted, seemingly by someone from the secret service. Then things turn out to be quite different.”

The Party Crasher

Another video that intrigued the two is about an actor who has to perform theater while he is in military service and can’t leave the barracks. Van Heusden: “As a filmmaker I work with actors like this guy every day. In a way he looks like someone you could run into in the Netherlands. But the things he has to deal with in life are things we can never imagine. We don’t have military service anymore. No angry generals to dodge before you go on stage.”

Actor in the Army

Through the films we learnt a lot about how incredibly inventive Iranians are in living their life ‘between the lines’. This actor for example: it’s easy to depict him as a victim of a religious dictatorship, hostile to culture. If we had done a story on him ourselves, we probably would have portrayed it that way. But the story he tells isn’t loaded with self pity, but is rather one of great resourcefulness.

Moreover: it is full of self-mockery and irony. Take the actor [from the video above]: he could have chosen to give a rant about military service. Instead he tells, with a twinkle in his eyes, how he managed to get on stage.

The makers wanted to keep that twinkle in the eyes. Despite the mask. That’s why they chose a technology that made the narrators unrecognizable, but not impersonal.

Still the form that was chosen by the duo, does not always go down well. The two often get the question of what is gained by having a mask, now that Iranians, who are some of the most ‘connected’ people in the region, share everything on social media. “We think that three quarters of the stories we got back wouldn’t have been told if it wasn’t for the relative anonymity of the masks.”

Van Heusden admits that there is no denying that the experiment has some catches. “They sometimes came with different stories than we had foreseen. But after a while we started to see that as the beauty of this project. This is what Iranians tell you when you don’t stick a microphone and your expectations in their face. But rather let them direct themselves.

When we got this next story back (see below), about an Iranian girl in a school in the Netherlands we first thought: what are we to do with this? But we really started to love the story. It shows how the Iranian form of civility Taarof, clashes with Dutch directness. About how we may seem to be similar but are actually very different. Fortunately so, by the way!”

The Pen