The genius of Louis van Gaal, the new Manchester United manager, is not easily understood.

For he is, in all likelihood, a genius. He led the biggest clubs of the Dutch, Spanish and German leagues to both championship titles, domestic cups, and international success. This in itself proves nothing, as anyone who happens to manage Bayern Munich, Barcelona, or Ajax , is bound to win trophies – even stuffed teddy bears, some suggest.

But Van Gaal also managed lesser sides to unlikely success. Last month, he was on the verge of entering the World Cup final with an unfancied Dutch team, perhaps the first Dutch side since the 1980s the country didn’t expect to win the title. Managing Ajax, a side with mostly inexperience teenagers, he reached two consecutive Champions League finals, winning one. In 2009, Louis van Gaal’s AZ from the small town of Alkmaar defied the odds and held off Ajax, PSV, Feyenoord and Twente to become the most improbable champions in Dutch history.

Van Gaal isn’t celebrated and neither are his secrets. That’s because his coaching genius is overshadowed by an image problem

This astonishing feat alone should have made him a Dutch football hero. (Imagine what would happen if Roberto Martinez wins the Premier League with Everton.) His management secrets ought to have been recorded and treasured for generations to study. But Van Gaal isn’t celebrated and neither are his secrets. That’s because his coaching genius is overshadowed by an image problem. Van Gaal is perceived as arrogant, red-faced, permanently angry, and socially inept.

And the reason for this perception is that it’s accurate.

Still, red-faced and socially inept Van Gaal is only his most visible incarnation. The more relevant and interesting version of the man lives insulated from cameras and journalists: on the training pitch, in boot rooms, in video rooms, and in meeting halls. Whatever it is he does there makes him this rarest jewel: a serial success in one of the most competitive businesses in the world – professional football.

This version of Van Gaal is poorly documented in the media, but that is hardly the media’s fault. Angry Van Gaal is just too irresistible not to broadcast – and Van Gaal can turn angry at the unlikeliest times. Stepping out onto the Rotterdam tarmac after the flight back from Brazil, Van Gaal and his players were welcomed by an enthusiastic crowd. A reporter for the Dutch public broadcaster NOS followed Van Gaal and recorded a characteristically cringeworthy exchange.

Reporter: ‘You have certainly moved some people at home.’

Van Gaal: ‘We all have, together. And also you as the media. [Laughs sarcastically.]

Reporter: ‘What do you mean?’

Van Gaal: [scoffs]

Reporter: ‘People can offer criticism, but they can also offer praise when appropriate. [...]’

Van Gaal: ‘In that case I deserved some more praise in recent years, also from the NOS…’

Reporter: ‘Well, now there is genuine praise from everyone .’

Van Gaal: ‘If you say that you are honest… well that’s not how it is…’

Reporter: ‘I don’t understand what you mean Louis… this is a great moment…’

Van Gaal: ‘You know exactly what I mean…’

He had barely set foot on the soil of a country that never loved him, but now, however briefly, did. (Recognition! Love, even! At last!) But instead of relishing the moment Van Gaal chose to settle scores.

However hilarious, interviews like this obscure the man’s brilliance. Fortunately, there are some good sources that describe his methods in detail, most of all the second part of his ghost-written autobiography Visie (‘Vision’).

Unfortunately, the book has all the charm of a Van Gaal press conference and is thus hardly an easy read. But careful study and a review of two interviews with the trade journal of Dutch soccer coaches have yielded valuable insights into the method that helped shape Holland’s unexpectedly strong performance at the World Cup and the work of his disciples José Mourinho and Pep Guardiola.

Louis van Gaal and Sir Bobby Charlton pose with a Manchester United jersey during Van Gaal’s first press conference after becoming the new manager of United.

1. Louis van Gaal is humble

It may come as a surprise, but it’s true: Louis Van Gaal is a humble man.

Admittedly, he does a sterling job at disguising this. And he has certainly shown no signs of false modesty towards his new employers. Asked whether it’s a dream to manage United, he said : ‘I don’t say it’s a dream, because I am 62 and I know what I can do and I think Manchester United know what I can do and I think that is why they have come for me and they were not the only club.’ And to Van Gaal, Sir Alex isn’t Sir Alex but simply ‘Ferguson’.

But Van Gaal is humble in the sense that he knows that he has, at best, a very limited influence on his team’s performance. In November 2001, Van Gaal resigned publically as Holland manager at a positively surreal press conference. There he said a great many things that deserve to be translated into English, but for the matter at hand this bit is the most relevant: ‘My greatest ability is that I can get an extra 10 percent out of a player. But [I can do this] only if everyone subscribes to the same idea.’

Economists agree with Van Gaal’s analysis. In Soccernomics, the economist Stefan Szymanski and the journalist Simon Kuper write that money determines somewhere between 80 and 90 percent of the performance of football clubs. That leaves 10 or 20 percent for other factors, one of which may or may not be the manager. Bas ter Weel, a Dutch economist who also studied the effect of managers on their football teams, compared their influence to that of prime ministers on the economy: probably no other single individual has more influence, but it’s still marginal.

Van Gaal understands this. So if he is to coax this extra 10 percent out of his players, if he is to matter at all, he is prepared to do near anything.

He told the trade journal De Voetbaltrainer that he had a floor of the Dutch team hotel in Noordwijk rebuilt in a way that he believed would help the players communicate better. He also had the hotel’s internet access rewired for higher broadband speeds to save his players who play online games from annoyance. Annoyed players are unwilling and unable to learn, and only once they are prepared to learn can they become better, so runs Van Gaal thinking.

Photo: Dean Mouhtaropoulos/Getty Images

The point is this: only if everything is perfectly tailored to the goal of transferring knowledge from Van Gaal to his players can Van Gaal hope to have a significant effect on his team’s results

The point is this: only if everything is perfectly tailored to the goal of transferring knowledge from Van Gaal to his players can Van Gaal hope to have a significant effect on his team’s results. If he should ever relent in this pursuit – if he ‘loosens the reins’, to use a phrase his successor Guus Hiddink likes – you might as well not be there at all.

Central to all of this is what Van Gaal calls the ‘learning process’. In 2009, his video analyst Max Reckers explained to me how Van Gaal uses video to aid the learning process. ‘[The reason] why people think he is so dominant over others is that he wants to control the whole process [of learning]. He wants to know about all the feedback players get about their performance: from friends and family but particularly from journalists. If he knows this, he can decide what video images and commentary he gives to the player. Every stimulus he gives is tailor-made to the player’s needs.’

Van Gaal tries to reduce interference with the learning process by minimising his players’ contacts with what he often calls ‘the outside world’. Until Van Gaal became Ajax manager in 1991, former players and journalists habitually hung out with players in the spelershome, the ‘players home’. He ended this immediately; access was to be denied to everyone except the players. ‘Only the people who worked at achieving the same goal were allowed in’, he writes in Visie. (Of Manchester United, he said this week: ‘We have to sing from the same hymn sheet.’)

In short: Van Gaal fully appreciates that his maximal theoretical influence as a manager is limited and so does everything to maximise it.

2. Van Gaal recognises the importance of the individual

Van Gaal has a reputation of ruling over his players like a humourless dictator and forcing brilliant individuals to conform to the collective. His clash with the great Rivaldo at Barcelona is well documented and at Ajax and Bayern Munich he clashed with players who didn’t (want to) understand his methods.

Certainly, Van Gaal likes rules and he doesn’t like making exceptions to them. A recent documentary on Dutch public television revealed that in his first stint as Holland manager Van Gaal set a rule that everyone – staff and players – should wear socks at all times. No bare feet in flip-flops, for example. This also counted for the assistant manager and former seventies great Ruud Krol, a man who, in the words of the Dutch press secretary, ‘had lived without socks for years’.

This may seem childish. But Van Gaal believes that rules like these provide a sense of common purpose and reduce the chance of quarrels and misunderstandings that can only distract from football. If the rules and habits are the same for everyone always, adherence becomes automatic. This, in turn, frees up time and energy that can be spent on – you guessed it – the learning process, which is key for Van Gaal to work his 10 percent magic. As Van Gaal has often said - and recently explained to the British press - he thinks that in order to play football well, one needs to think and act deliberately rather than intuitively.

‘Structure gives logic to thinking and doing and people thrive [in such an environment]’, Van Gaal writes in Visie.

Photo’s: (left) Robin Utrecht/HH, (right) Dean Mouhtaropoulos/Getty Images

Having created this structure, as he has already done at Manchester United by issuing a mandatory collective lunch rule at 1 pm, Van Gaal sets about studying his players individually. He does so rigorously, both on and off the pitch. In fact, Van Gaal has a much-ridiculed name for his approach: “Het Totale Mens-Principe”, which translates as the Total Person Principle or Complete Human Principle. As he explained to the Dutch FA’s own website Ons Oranje: ‘A pass from A to B is not just that pass, that technical skill. There is actually a whole human being behind that pass. And that human being is influenced by its mind.’

‘A pass from A to B is not just that pass, that technical skill. There is actually a whole human being behind that pass. And that human being is influenced by its mind.’

In order to influence his players’ minds, Van Gaal, when managing AZ, called in the help of psychologist Leo van der Burg, who ran a consultancy business in ‘scientific business humanities’. Van der Burg features heavily in Visie and was one of the drivers behind Van Gaal’s newly found appreciation of the individual. Van der Burg – who wrote a book titled Do What You’re Good At – taught Van Gaal and his staff two lessons: 1. It’s better to work on a player’s strong suits and 2. Every player is different and warrants a different approach.

To properly tailor his efforts, Van Gaal needed to know what his players were like outside of their football identities. Before he met Van der Burg, Van Gaal used to visit most of the players he wanted to sign at their homes, took notes, and then made reports of what he registered. But these reports turned out to be useless, he writes in Visie. ‘[T]hey turned out to be too much of a snapshot [rather than a rounded profile, MdH]. So I called in the help of a professional agency that, together with me, profiles the players.’

Using these profiles, Van Gaal divided his players into three colour categories that Van der Burg devised: blue players, who are ‘intellectually orientated’; green, ‘emotional’ players; and ‘creative’ red players. These three categories differ in the way they process information, which guides Van Gaal’s communication with them. This even passes into the half time break, when he uses different pitches in his voice for the different kinds of players, Van Gaal explains in Visie.

The same principle applies to the feedback players get after games. As Van Gaal’s video analyst Max Reckers explained, players are always shown successful passages of play because positive images stick in peoples’ heads more easily and make for faster learning. Other than that, all feedback is tailored to the individual and depends on the circumstances. Did a player get critical questions about a certain play? Or perhaps a journalist was very positive about a particular decision a player made that Van Gaal and his staff were actually critical of? Red players will get different video and commentary from Van Gaal than blue players.

Probably Van Gaal has developed his methods even further over the last few years. In football tactics, individual players have become more important to him. In the 1990s, Van Gaal preferred to pry open defences with a collective of well-organised teenagers hoarding the ball on the opponent’s half and patiently passing their way to decent chances.

Photo: Dean Mouhtaropoulos/Getty Images

But as football has evolved, so has Van Gaal. By the time he took over as AZ manager in 2006, it had become apparent to him that this could no longer be done. He built his team around the brilliance of unpredictable players like the Dutch-Moroccan striker Mounir El Hamdaoui, who could do as he pleased. At Bayern, he made the great dribbler Arjen Robben his most important player.

Moreover, he now also accepts that the availability of a single player can change much, if not everything. When midfielder Kevin Strootman tore his cruciate knee ligament in March, he quickly decided to ditch his favoured 4-3-3 system and replace it with 5-3-2. The old Van Gaal would have simply shown another player a sheet with instructions for Strootman’s position; the other player would henceforth be Strootman. (In fact, for this reason Van Gaal still loves versatile players like Thomas Vermaelen.) But he now accepts that individuals matter. The decision to change his formation surprised many but it only took him three games in charge as Holland manager to identify Strootman in De Voetbaltrainer as the irreplaceable cog on which everything in midfield depended.

So yes – while Van Gaal will issue many odd rules and while he will use the word collective often, he appreciates that the collective is made up of individuals.

3. Van Gaal fears the media but doesn’t manage the media

British journalists, be prepared: Louis van Gaal disdains you. In his mind, journalists and reporters are lazy and have no knowledge of football. Their ignorance alone is enough to enrage him.

Van Gaal is honest in the sense that he can barely hide his opinions – expect to be patronised whenever he thinks you asked a stupid question. His wife, a former PR manager for an insurance company, has given up trying to help him. In a piece you might want to learn by heart, writer Peter Zantingh explains: ‘Even if he has won and seems to be quite happy, one wrong question can - and will - put him off.’ And if you want to entice him to say something newsworthy, he will notice, but eventually you will succeed.

But there is more to his scorn than mere impatience with the media’s supposed sloth and stupidity.

At one stage during the press conference in 2001, in which he announced his resignation as Holland manager, Van Gaal briefly scratched his nose. When he heard photo cameras click excitedly, he became angry. He unkindly requested that the media not print pictures of him scratching his nose, ‘just because they [the media, MdH] want to illustrate a certain tendency’.

Clearly, he knows how mass media function and how reality gets distorted to fit a narrative. But he simply doesn’t accept it, even though he knows he can barely influence it. ‘The media know that you have been a schoolteacher [Van Gaal was a PE teacher for years, MdH] and so they ask questions and write pieces in that context. They slap a label on you and you carry that around forever’, writer Maarten Meijer quotes Van Gaal in his biography of the man.

To Van Gaal, the single biggest disturbance of the learning process is the media. Not only do players hear what is being said about them, the media reports influence those who are closest to the players

The lack of football knowledge he perceives in journalists irritates him even more. The media, he writes in Visie, will often ascribe the loss of a game to a lack of effort or a lack of ‘hunger’: ‘The media always write this: they didn’t put in enough effort […] When the layman says: he [a player, MdH] doesn’t try hard enough, then usually something else is wrong. The squad might be positioned wrong tactically, which results in someone showing up late time and again, which then makes it seem as if that player lacks sharpness or isn’t trying hard enough.’

In a profile of Van Gaal in the Dutch weekly Vrij Nederland, his brother Gerard offered seemingly sound advice about what to do with dumb questions: ‘Simply decide that stupid people can’t insult you.’

But the stupidity never insulted Van Gaal as much as it worries him. As Max Reckers says, with Van Gaal everything is about learning. And the single biggest disturbance of the learning process is the media. Not only do players read and hear and see what is being said about them, the media reports influence those who are closest to the players. One reinforces the other. ‘This is a dangerous mechanism, because the players have the tendency to parrot what the media say to them’, Van Gaal writes in Visie. This can lead the players to lose faith in Van Gaal’s methods, which in turn leads them to accept less and learn less from him, which all nibbles away at his 10 percent window for improvement.

As he said after some critical media reports in the Dutch media in the first week of the World Cup: ‘We all need to be pulling on the same rope.’

4. Van Gaal cares more about the process than about the result

There is a fair chance that in the beginning of the season, Manchester United will drop points against unfavoured opposition. This usually happens after Van Gaal takes charge somewhere. After such a loss, Van Gaal will say that he thought his team played well or even brilliantly, even when he is the only person in the stadium who thinks so. Several of these post-match interviews have turned into minor Dutch internet classics.

He’ll say that he saw ‘a very different game’ than the reporter did. And it’s true: Louis van Gaal watches matches differently than most anyone else

He’ll say that he saw ‘a very different game’ than the reporter did. And it’s true: Louis van Gaal watches matches differently than most anyone else. While the fans and the media attach a lot of value to the score, Van Gaal looks what the players have done; whether they followed instructions. If a player acted according to plan, Van Gaal is satisfied, because that plan was part of the long-term learning process. ‘In a way, it’s not about the result’, he writes in Visie, ‘it’s about the quality of play […] with the ultimate goal to keep on improving that quality of play.’

Yes. But then there’s these pesky little reporters, who only consider the score. ‘[Media] always use this unimaginative reasoning about the score’, Meijer quotes Van Gaal in his biography. ‘The press reasons: the team scores too few goals, so they must be playing badly. But you could also see it another way: given the fact that we play wonderfully, we should score more.’

The last match Holland played before heading off for Brazil, a friendly against Wales in Amsterdam, wasn’t easy on the eye. The traditional so-called farewell game is usually a viewer-friendly exhibition game against a poor opponent, featuring many goals to energise the home front before the World Cup. Instead, Van Gaal tried out three different tactical formations and bored the capacity crowd to death, and afterwards had a ritually tense exchange with a television reporter.

But then Van Gaal only plays friendlies because his employers are somehow obligated to. ‘I coach my players situation by situation’, he explains in Visie. ‘This is only possible during practice. There, I can say ‘stop!’ and halt the game and create a learning moment. In a friendly that’s not possible. I don’t think the referee would be very happy if I tried.’

Van Gaal’s focus on process rather than outcome explains his preference for young players who want to learn and become better players. As Bart Vlietstra wrote in a pre-World Cup piece in The Guardian, the young Feyenoord defender Bruno Martins told Van Gaal in their first meeting that he ‘would really like to become better. I would like to ask you a lot, Mr Van Gaal."

Van Gaal: ‘That’s a good thing, because I can help you with that.’

Martins Indi: "Really?"

Van Gaal, beaming: "I love you already, Bruno."

5. Van Gaal is forever seeking new football knowledge

Van Gaal is always on the lookout for new knowledge about football. ‘Louis values innovation a great deal’, Max Reckers says in Visie. ‘The amount of time he puts into this is unbelievable. You don’t see that anywhere else in football.’

In 1993, Van Gaal was the first manager in The Netherlands to kill the endurance run as a tool to make players physically fit during pre-season training. He cut the tradition as soon as his physiologist Jos Geijsel told him that endurance runs make players slower, something Van Gaal had suspected during his career as a player.

When a daughter of an old friend wrote her master’s thesis at VU University about the optimum time a football team should take to prepare for the next match – three days, not four as Van Gaal used to do – Van Gaal immediately implemented her advice. (Four days was judged to be too long for players to keep their focus on a specific opponent.)

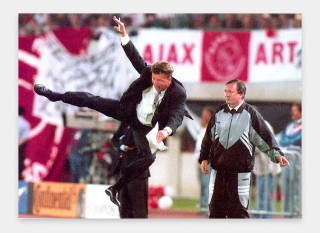

Van Gaal as Ajax manager doing a karate kick in the 1995 Champions’ League against AC Milan. Photo: Robert Jaeger/ANP

Van Gaal studies other sports. When at AZ, he exchanged knowledge with managers from Aussie rules football. He also copied methods from field hockey

And, Van Gaal studies other sports. When at AZ, he exchanged knowledge with managers from Aussie rules football. He also copied methods from field hockey, which is popular in The Netherlands and whose practitioners are generally more highly educated that the ones in football. His wish to show players their actions in video led him to recruit Reckers, who had worked as an assistant coach at a top-level hockey club and was an expert at using a sophisticated video analysis tool. Their focus on detailed video analysis and the use of expensive equipment has kept evolving, as Manchester United players and staff at their Carrington training ground have already learnt.

Reckers and Van Gaal have kept improving their video systems and have made use of both Google’s Glass and the Oculus Rift gaming head set, which enables them to judge every situation that happened on the pitch from the perspective the players had at the time. This makes for a fairer evaluation of both the individual player and of the squad’s ability to generates enough outlets for players to pass the ball to.

Sitting in Manchester United’s pretty brick-walled dugout, Van Gaal will continuously take notes as the disciplined data gatherer that he is. When at Bayern Munich, he once famously gave every player a piece of paper with the strength and weaknesses of their direct opponents on the pitch - even when the opponent was a fourth-division amateur side.

Over the top? Perhaps, but Van Gaal’s reasoning is that he always gives his players that sheet, no matter how feeble the opponent. He approaches every game in the same way in order to create the structure and automatisms he deems necessary for his players to learn and learn. Knowledge and technology are allies in his quest for that extra 10 percent.

6. Van Gaal adapts

Van Gaal is seen as a staunch proponent of the so-called Dutch School of football. Precisely what this is no-one in the Netherlands knows for sure, but any definition involves 1. playing with two wingers 2. having a large majority possession and 3. stringing together lots of passes on the opponent’s half.

‘I sometimes think that I’d rather want my teams to play the game well than to win’, he says in Visie. ‘I want my teams to be remembered.’

In this past World Cup, we have seen Van Gaal the pragmatist. He played without wingers, used five defenders, gave up possession of the ball voluntarily, and, in doing so, earned a tsunami of criticism from the Greek chorus of Dutch football pundits. Whether Van Gaal’s ‘un-Dutch’ approach was a one-off or whether he has introduced a new School of Pragmatism remains to be seen. But Van Gaal is obviously not a dogmatist anymore.

At Manchester United he will be able to field eleven players who belong to the very best in the world at their positions, so he will probably adopt a play style more similar to the classic Dutch School. He probably won’t revert to the ball-hoarding style of Ajax in the 1990s and Pep Guardiola’s Barcelona and Bayern Munich teams. Van Gaal thinks Spain and Guardiola’s teams are less effective and fun than they can be. Their problem, Van Gaal thinks, is that they try to gain possession in situations when the opponent’s defence is well organised. This results in horizontal or back passes and mind-numbing ball-hoarding. ‘Less fun to watch’, he told De Voetbaltrainer.

During a photo shoot with FC Bayern Munchen. Photo: Hollandse Hoogte

So he prefers a different style, one which he has given yet another curious name to: ‘provocative pressing’. By this he means that he will not press the opponent immediately after losing possession. Instead, he will yield the opponent some time and space, provoking them into surrendering possession higher up the pitch. Then, his team quickly passes vertically, in order to profit from the space behind the opponent’s defence - see for example the second goal against Chile in the group stage of the World Cup.

Perhaps ‘provocative pressing’ is simply a euphemism for counter-attacking football, which to Dutch football ears is a swear word. But after the annus horribilis that was Manchester United’s previous season, Van Gaal probably won’t suffer the same burden as Dutch coaches – that they need not only win, they need to win in style.

The first few weeks and months will probably be decisive weeks for Van Gaal’s tenure. If results are bad in his first couple of matches, then a vicious circle of losses leading to bad press leading to tense media exchanges leading to more losses may be inevitable. Probably the English press underestimates Van Gaal’s customary blunt Dutch way of telling everyone the truth-as-he-sees-it. And just as probably Van Gaal underestimates the cruelty of the tabloids.

But once that hazardous initiation period has passed, past performance from both Manchester United and Louis van Gaal – serial winners – suggests they will come good.